I am perfectly content and at ease with the natural environment of the bounteous planet on which I live and the universe beyond it. With these I have no conflict. Yet I feel an overwhelming incompatibility with human society, particularly the one in which I was born, raised and spent the greater part of my life. Notwithstanding, I do not find it difficult to construct in my imagination the form, tenets and protocols of a social order that would be benign to all, including the elite of the present order.

I can say, in all honesty, that I have worked extremely hard throughout my entire life. Yet now in 2024 — my 82nd year — I am in receipt of a total personal income of £92.49 per week [US $111.46], which is reluctantly given by a society that officially regards me as a "lazy good-for-nothing layabout who doesn't think he ought to contribute to society".

That is 23% of the contemporary [2024] UK minimum wage and 16% of the UK average wage in 2024. I have no other source of personal income. Obviously, I could not even contemplate returning to the UK.

This amount is not inflation protected. It will stay at £92.49 per week for the rest of my life, provided it does not disappear altogether as a result of some kind of administrative oversight. This means that in 10 years time [if I am still alive] it will have only half the buying power it has now.

In Brazil, where I live, it is 1·64 times the Brazilian minimum wage. Gratefully, I am sustained by the unfailing support of my wonderful Brazilian companheira. People here don't subscribe to the infantile "It must be yer own bloody fault!" quip made by certain elements of the British press.

Hard work and no money suggests to me that I must be somehow incompatible with the economic system under which I am constrained to live. So what precisely is the nature of this incompatibility?

It is not a lack of relevant technical skills, talents or abilities. I have plenty of these. It is not lack of motivation: I have always driven myself hard. I am naturally self-motivated. So it must be something to do with the way I interact with society. Yet I have researched, learned and applied all the established approaches and procedures for acquiring work and doing business. I have been honest and truthful in my interactions with people, so the fault is not with my character [although I concede that honesty and truthfulness do not appear to be attributes of those who succeed in business]. The only thing left that could be the culprit of my incompatibility with the incumbent social order is my personality.

My Personality

I am very sensitive to sound. I remember crying all the way through a drum recital by an older pupil at an end of term function at my pre-infants school. Even today, extraneous sounds easily annoy me and significantly disrupt my thinking. The sound of children's voices makes me cringe and feel extremely uncomfortable, especially when they are playing games. The same is true when a significant number of adults takes part in a social event such as a party.

I am an obsessively hard worker: a self-motivated perfectionist. I relish long periods free from interruption and distraction so that I can concentrate on my current obsession. I have zero tolerance for untruth, whether heinous lies or idle bullshit, because their content has no part with universal reality. I am a deeply caring person and feel empathy with others in both joy and suffering. The problem is that it does not show in my face or body language. My generally expressionless face, and deliberate avoidance of eye contact, seems to convey that I have an air of arrogance or offishness towards people. Although I am not in the least arrogant, this perception on the part of others imposes a communication barrier, generating within me a social ineptness that cuts me off from people.

As a result, I was bullied: not so much at school but certainly on the 16 mile bus ride I had to take every morning and evening. This bullying was perpetrated entirely by pupils from other schools who did not know me well. The bullying was done entirely by girls. I suffered this for 5 long years, until a female teacher from one of those other schools befriended me and we sat together on the bus and talked about life, the universe and everything. I can fully understand that my personality must have appeared weird to these bus kids. I don't criticise them for being offended. But their reaction: that of relentless bullying, I consider to be inexcusable. My social ineptness hit home when, while in the sixth form, my father forcefully criticised me for never having brought a girl home to visit. Truth is, I did not know any.

My parents seemed to me to be excessively intolerant of me but not of my sister. I could say something which to me appeared quite casual and trivial, which would precipitate a tirade from my mother and anger in my father. Life was like walking on egg shells, wondering when I would next get my head blown off and not knowing why. My father used to clout me over the head for saying things and I could not understand what I had said that was so offensive. It alienated me from him. If it happened in formal company he would scold me, broadcastingly call me an idiot and cold-shoulder me for the rest of the time. In fairness to my father, he did have a brain injury during the Second World War, which changed his personality. This probably also affected my mother. I don't think my parents had any idea that I was somehow 'different'.

The only physical obsession during childhood that I can remember is that I would wash my hands frequently — at least repeatedly dipped them in water — when I was gardening; a habit which irritated my father and for which he criticised and scolded me. However, I do also remember that I had a seemingly oath-bound unconditional obligation to trace out — with obsessive precision — the routes that I walked, including walking around obstacles, which were once there, but were no longer.

I always saw a stark contrast between my sister and me. My sister was educable: I was not. Like the vast majority of pupils, my sister absorbed her taught curriculum, apparently without question. Something within me prevented me from just blindly accepting what I was taught. Whatever I couldn't validate, through critical thought, just wouldn't stick. My parents would tell me, "learn what you're taught, pass your exams, go to university, then when you're older you can think critically about it". But I couldn't. I wasn't being mule-headed. I had no control over it. I was unable to accept anything conveyed to me via the spoken or written word unless or until it had been substantiated by observation or experiment, or at least, seen as ostensibly consistent and compatible with what I had already observed or experienced.

So it would seem that my mind drew a firm involuntary distinction between information derived from direct observation on the one hand, and, on the other hand, information conveyed via symbolic language. The first, within the limits of human sense and perception, could only be truth: the second could be true, false or a composite mixture of truth and falsity. This became a life-long rod for my back, for which, in the long term, I have become eternally grateful.

The summer I was 10 was the last time I ever went on holiday with my parents. My father had said that I always ruined their holidays. I had no idea why and he would not elaborate. On the other hand, my sister — as a child and later throughout her married life until my parents died — always went on holiday with them. After I was 10, I spent my summer holiday time with my grandparents. When I was 13 my father took me to a YMCA camp in the Lake District. I was sent back there each year alone from then on. When I was 14, I was abused there by a homosexual staff member. When I went there with a school friend, at the age of 16, I was falsely accused by the camp chief of molesting little boys. The accusation, I discovered, was originated by the homosexual who had abused me 2 years earlier. After that, I spent my holidays at home alone.

During one of those holiday periods at home alone in my early 20s, I became depressed through loneliness. I loaded my Cooey ·405 magnum BB gun and put it in my mouth. I screamed and was about to pull the trigger when two men, who worked an allotment at the bottom of our garden, walked past the window. They looked inside, startled. I hid. I lived.

When I entered the world of work, my bosses and work colleagues complained that my facial expression conveyed nothing about how I felt or what I was thinking. They said I would make an excellent poker player, although I wouldn't really because I can't stand games. It seems that when I thought I was reacting facially — smiling, for instance — my physical face was not smiling: it was still blank or was projecting some other inappropriate expression. It was only my mind that was smiling.

I suspect that my face's propensity to involuntarily project a blank or inappropriate expression has led many people, especially those in official positions, to seriously misread my intentions and character. Consequently, when the archetypal Government Standard Jobsworth Plank casts his stern official eye at me, saying "I know your type", "I can see you coming a mile off", "you can't pull the wool over my eyes", he is always and inevitably way off target. The resulting disproportionate amount of aggressive verbiage I have had to endure, especially, from public officials has left me with a fear of, but indelible disrespect for, authority.

In a community-based society, this could never have happened. In such, everybody around would know me and immediately see the total absurdity of me doing such a thing. But in a society controlled by faceless bureaucratic hierarchies, anybody — particularly anyone with any degree of neurodivergence — is vulnerable to this kind of official mistreatment.

Consider this: if sentient human beings can misread us 'aspies' so ineptly, then what, pray tell, will the new rash of evermore ubiquitous AI-driven public surveillance systems make of our facial expressions and body language? I would surmise that such non-sentient systems will forever be fundamentally unable to metricate neurodiversity from a facial image. Thus, such as we, can look forward to a lifetime of regular detentions.

As time passed, I began to master the art of hiding or circumventing my personality, and the facial non-expressions it precipitated. I achieved this by role-acting rote-learned social norms. However, the mental overload of this continuous role-playing was extremely fatiguing. During the 1970s, I worked in an office located in the tranquillity of an old mansion, way out on a country estate. There, while my colleagues went to a local country pub at lunchtimes, I would head off down a forest path, spending the lunch hour just walking alone, in order to relax my mind and take a break from the stress of my continuous role-act.

To act the role of a socially-compatible individual, one needs a frame of reference for what is, and what is not, socially acceptable behaviour and conversation. I had, since adolescence, known that other people seemed to have this frame of reference naturally in-built, whereas, for some obscure reason, I didn't have it. While still at college, I stumbled across the idea that perhaps religion could supply what I needed. Most religions to me appeared to be either deceptive instruments of social control or some form of emotional escapism. I selected one that seemed to have some vestige of pragmatism and followed it for 14 years until my intentionally suppressed propensity for analysis forcibly brought me to book regarding its all too obvious flaws and falseness. I ditched it. But, by then, I had accumulated sufficient sociological data from which I had built a knowledge-based frame of reference, which I used in place of the natural one that most people seemed to have been born with.

I can neither bestow nor accept deference, even if I try to pretend. I am far too transparent. I also have an inherent distrust for all forms of authority. The notions of deference and hierarchy are anathema to me. Thus, at work, I did not accept willingly the concept of a boss telling me what to do. Fortuitously, I always seemed to fall into a job in which I was essentially self-managing. This began because I was a programmer in a company where management knew practically nothing about programming. The use of computers was very new. Later employers seemed to relish my self-managing aspect because it saved them the task of managing me.

I do not see truth as a function of location, circumstance or company, although I would have no compunction about lying to save life. This makes me liable, at times, to say what most would consider to be inappropriate. Such often merely comprises overtly blunt truths, which people generally consider better not said or at least kept from view. At work, this led to my gaining a reputation with management for being what they termed "undiplomatic". While at college in 1962 I told a joke which my greatly revolted colleagues considered totally inappropriate for the company present. I couldn't see why at the time. I also have a propensity for providing what most would term "too much information", which contrasts sharply with their complaints that my facial expression and body language provide too little.

I feel uncomfortable as part of a group of more than 4 or 5 other people. In a group of more than 7, I tend to stay silent and unassertive. By consequence, I never had many 'friends'. I still don't.

At my primary school, these 'few friends' were almost invariably colleagues who shared the same narrow interest. At primary school, I was one of 3 introverted friends who always went around together. Our common interest was to 'investigate' all kinds of 'suspicious' objects and events within our school locality.

On pressure from my father, I diverted one day to try to take part in an informal football match with the friends of the son of one of my father's friends. This happened only once but I was devastated when my original two friends shunned me from then onwards. The football match had been a lost cause from the outset.

I am physically clumsy, although not obviously so. I also have a lazy left eye, which means that I cannot see stereoscopically and therefore cannot judge speed, direction and distance accurately at close quarters. Nonetheless, lack of physical coordination and stereoscopic vision means that I can't play football or cricket because I can neither throw, catch nor kick a ball. It just doesn't work, no matter how long or hard I try.

I remember on other very rare occasions when my father would decide to pick me up from school. Before taking me home, he would butt in to a kick-about with a bunch of other kids. He would kick around with them while I waited on the side. He would only notice me afterwards and would bellow at me: "Why don't you just muck in?". Later at grammar school in Blackburn we would be taken to the playing fields at Lammack village. I would be idiotized by the coach for my ineptness.

At my secondary school, I was again one of 3 somewhat introverted friends. We were linked by a common interest in short-wave radio. I also remember spending much time at home alone happily pursuing this hobby of building and operating short-wave radios and erecting varieties of aerials and antennas.

On the other hand, I can give talks to large audiences. But this is not an interactive situation: it is a monologue. I remember giving the most enthusiastically received sixth form talk of my year to all three sixth form classes combined presided over by the headmaster. It was a heavily illustrated talk about the history of guns for which I borrowed a large number of small arms from a friend of my father's who was a gun collector.

I have always had great difficulty interacting with people and forming lasting relationships. When I left school I immediately lost touch with my 'friends'.

I hate team sports. I was forced to play football at one school, rugby at another and cricket at both. I am definitely NOT a team player. On the other hand, I love running because here I 'compete' only with myself and the clock. Until I was 72 I ran mini and half-marathons.

This reveals another immutable aspect of my personality: I am inherently uncompetitive. I remember my father chastising me after one primary school parents' meeting because the headmaster had said to him "... he seems to have no desire to beat his peers", in the sportive and academic sense of course. I can never understand society's obsession with competition. It achieves nothing but to dissipate the vast majority of human effort working against the efforts of others, thereby neither creating nor producing anything. It seems strange that, having been immersed all my life in a competitive society and raised in a family with an ingrained ethos of competition, I am inherently non-competitive. It is not a reaction on my part: it is simply the way I am.

Being inherently uncompetitive, I naturally embrace the notion of cooperation. Sadly, my difficulty in forming relationships with others renders me inept at working or playing with others. Thus, for me, cooperation is extremely stressful, even though I relish — indeed crave — the idea.

Even from an early age, examinations were, for me, an impervious barrier to progress. I simply could not pass them. I failed the 11+ examination even though my junior school headmaster had told my parents not to worry and that I would sail through. So I could not go to grammar school. I managed to scrape through the 13+. This was an optional examination taken two years later by those who failed the 11+. So now I could attend grammar school. Through a fortuitous move, I was able to attend the second to top ranked "red brick" grammar school in the UK. I gained English 'O' level a year early [a splinter skill]. But I did badly at 'A' level, having to re-take mathematics a year later at evening class. I tried a diploma in advanced technology and also an external university degree in Maths & Physics. I flunked both. Notwithstanding, these failures were not through lack of effort, knowledge or ability. I simply had an immovable subconscious contempt for exams. I had no control over this. To me, exams weren't the real thing. They were a sham.

I am an excellent observer. I can focus intensely on detail, but can also zoom instantly to, and back from, a grand overview — an ability I am told is quite rare. I am very bad at reading: I am dyslexic and dyscalculic. I have only managed to struggle through very few books in my life. I have never bought or read newspapers. To me they are a disorganised mess of disconnected bits and pieces of irrelevance. The same with magazines. By contrast, I am an excellent writer, having completed a book with associated articles totalling well over 1·4 million words.

My teachers and mentors always told me that if I wanted to write, I would have to read a lot. I never read a lot, but have written and published over 1·4 million words. So, from direct experience, I cannot agree with what my teachers and mentors told me. What is now clear to me is that to be able to write a lot, one has to think a lot.

I don't understand money: or more specifically, the notion of monetary value. To me it is a paradox — an arbitrary yardstick, of capricious elasticity, used by those with economic power to compare an immense diversity of like against unlike, in terms of one single dysfunctional universal measure that has no basis in physical reality.

The closest natural analogy to money I can think of, is a radioactive material whose elements [atoms] decay spontaneously into lighter elements [smaller atoms] plus fissile products comprising alpha particles, neutrons etc. and radiant energy [generally gamma rays]. A radioactive material is thus said to have a half-life, which is the time it takes for the original material to halve its substance as a result of radioactive decay. Analogically, the value of a monetary unit decays at a certain rate. Thus, for example, the British pound could be said to have a half-life of about ten years. The difference is that monetary value, unlike a radioactive substance, decays into nothing: aliquid in nihilum. But as it decays, the Gods [the bankers] create more of it, out of nothing: creatum ex nihilo, so they always have more money to lend and spend.

Pragmatic observation demonstrates clearly to me that money has little or no bearing on work, virtue or merit. On the contrary, I can see it relentlessly expediting its indisputable purpose of concentrating wealth, generated by a deluded many, into the laps of a devious few. If money be a measure of anything, it is simply one of hegemony, which, to my mind, has neither social morality nor economic virtue.

I managed to sustain a business for 15 years, mainly from work put my way by a former colleague and also by relatives who had businesses. I approached the task of creating business contacts in a very methodical and systematic way. I planned and drew stylised maps of my proposed territory. I wrote a comprehensive highly efficient contacts management software package, which government sponsored business advisors hailed as the best they had seen and drafted plans for me to sell it big-time. Through fortuitous contacts, I did manage to sell about 15 units, which I understand proved valuable and beneficial to its users. Notwithstanding, I personally was completely useless at using my own package. I did not mind sending mailshots but I hated and dreaded making unsolicited telephone calls. That is because I am clumsy at conversation. I well remember the single telephone response I had to a vast mail-out to the county business association of a brochure designed and produced for me by a professional design house. I was tongue tied and confused, consequently losing the contact and any potential business. I also hated and dreaded face-to-face encounters in which I was supposed to try to sell my product and services to business people. So my business gradually petered out to the point where I had to gracefully close it down in April 1991 at the age of 49 and sign on as unemployed. I never again received financial remuneration for my work.

This propensity for avoiding social contact is not just in business situations. It is in all situations. For me, it is a universal impediment. For example, when travelling alone, I always forego refreshments: simply to avoid the social interaction necessary to buy them. When I eventually found the courage to travel from Belo Horizonte-MG, Brazil to Québec City, Canada in April 2024 to see my grandchildren, I avoided buying anything during the two interchanges at São Paulo and Toronto.

It would be remiss of me not to mention at this point that there are other unrelated factors that have exerted extreme negative pressures on my efforts to maintain gainful economic activity. My fragmented education did not help either.

Internally, throughout my entire life, I have been regularly and all-consumingly tormented by repeating mental scenarios of horrible past events. I have since learned that, in clinician's parlance, this is known as looping. These can trigger at any time, whether I am in bed at night, or during the day, but invariably when I am alone. They mostly relate to injustices I have suffered from people in authority, which still perturb me because there is nothing to stop them, or something similar, happening again. They are not dreams. They are devastatingly vivid, true and accurate. Notwithstanding, they have a positive side in that I think the same mechanism that causes them also bestows upon me a propensity for lateral thinking and constructive imagination from which new ideas are born and develop.

What Could I Do?

A person can change his character. For example, he can overcome dishonesty and, by sheer will-power, become honest. Not so with personality. A person's personality type is what he is born with. It may be influenced in some way by his formative social or family environment. I don't think science is really sure about this. But in a figurative way, one could say that it's the way his brain's wired. And that is a fait accompli: it is something he cannot do anything about.

Notwithstanding, a person with a particular personality-type can act the role of a fictitious person with a different personality-type. For instance, a geeky introvert can act the role of a flamboyant salesman. I did this. And it worked up to a point. But I always found it difficult and stressful because I knew it was a sham, which I found distasteful. Yet, throughout what should have been my working life, I played this role. But it simply wasn't me. Consequently, when I reached retiring age, I stopped, instantly reverting to the way I really am. I became me again.

From when I signed on as unemployed in April 1991, I was obliged to seek work during every working day. This I did diligently until April 1997. During that 6 years, thoughts had been running through my mind concerning why things were the way they were for me. I was living a wasted life. I knew by then that I had no chance of finding work. So I decided to give myself a job. I knew I could not run a business so I decided to create and pursue a personal project to try to make sense of my life. I started to write. My first written work was a short poem, all of which came into my mind as a torrent of words that just fell into rhyme. For the following 22½ years, with the poem as its basis, I wrote a book accompanied by more than 300 footnote articles, which together returned a count of over 1·4 million words.

In April 1998, I mounted what I had written so far on a web site. That website, entitled Life, the Universe, Society and a Better World, is finally [in October 2025] complete. From 1997 to 2004 I continued my daily task of seeking work as required. However, now seeing this as a futile chore, I gave it only the minimum necessary and sufficient time and effort to satisfy the bureaucratic requirements to qualify for the receipt of social security benefit. Finally, frustrated and exhausted by my Draconian life in the United Kingdom, I emigrated to Brazil in 2004, where I continued to work full time on my writing, under the unfailing support of a very kind friend.

My entire life thus far had been a forcible demonstration that I simply didn't fit. It looked to me as if I had somehow been predestined to be forever a stranger in a strange land. However, in late 2019, a flurry of short news articles appeared on the Web about Asperger's syndrome. On reading these, lots of bells began to ring about my whole life and the problems I had interacting with people and forming lasting relationships. I wanted to find out if I had Asperger's syndrome, but on an income of only £92.49 per week, I was unable to afford diagnosis by a professional psychologist or neurologist. My only option was to seek free psychological battery tests on the Web. I found several that seemed to have good credibility and took 3 of them.

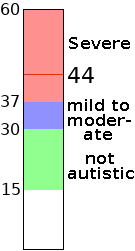

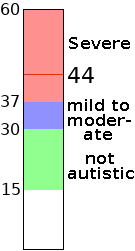

These tests determined that I am between 67% and 87% neurodiverse, which, from what I can glean, signifies that I have a form of high-function autism, previously called Asperger's syndrome. My autism spectrum quotient [AQ] result from a Web-based test devised by the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge is 44.

This discovery was quite a personal shock at the time, although it gave me a great sense of relief that I now had some kind of excuse for my life-long failures: academically and in business and social relationships. I don't know where this leaves me or where I go from here, if anywhere. Nevertheless, it seems that I was the type of child that Dr. Asperger referred to as his "little professors". My nickname at primary school was "professor". They called me 'Prof'.

These tests determined that I am between 67% and 87% neurodiverse, which, from what I can glean, signifies that I have a form of high-function autism, previously called Asperger's syndrome. My autism spectrum quotient [AQ] result from a Web-based test devised by the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge is 44.

This discovery was quite a personal shock at the time, although it gave me a great sense of relief that I now had some kind of excuse for my life-long failures: academically and in business and social relationships. I don't know where this leaves me or where I go from here, if anywhere. Nevertheless, it seems that I was the type of child that Dr. Asperger referred to as his "little professors". My nickname at primary school was "professor". They called me 'Prof'.

Fairly recently, the term Asperger's Syndrome seems to have been dropped from clinical definitions. I understand that this is because Dr. Hans Asperger, who did the original research, is reputed to have had some role in Hitler's Eugenics Programme. If he did, it was probably because he was given a choice of either cooperating or a bullet in the head. His description of his "little professors" fits me with an uncanny degree of precision. Consequently, even if the same neural mechanisms may be responsible for all forms of 'autism', what I perceive as my own mental state of being is very different from what appears to be popularly known as autism. So, I think the separate term 'Asperger's Syndrome' is much more appropriate than to lump everybody into a single continuum or 'spectrum'.

Of course, since this is not a 'professional' 'diagnosis', it will not alter my life in any way whatsoever. I will still, now aged 81, be officially expected to continue sustaining my biological existence on £92.49 a week! In December 2023, I took a Test to assess Asperger Syndrome devised by Aspergers Anonymous. My answer was YES to 19 out of the 20 questions.

The professionals concede that Asperger's syndrome is not an illness. Nevertheless, they do refer to it as a developmental deficiency or as a disorder of some kind. This implies that some aspect of the make-up of a person with Asperger's syndrome did not develop correctly or completely. Thus, anybody with a personality-type that sees the world differently from the way the incumbent mainstream sees it must be somehow deficient. It is tantamount to a capitalist regarding a socialist as having a deficiency, and vice versa.

Notwithstanding, when I look honestly at myself, the term deficiency does not appropriately describe my difference from others. I do not feel deficient: I feel incompatible, which is definitely not the same thing. And this feeling of incompatibility is with the suffocatingly narrow options that are ruthlessly imposed upon me, by the society in which I am constrained to live, under the threat of State violence, which would surely be unleashed upon me were I to try to follow what I clearly see as the morally correct way.

On the other hand, something that could be termed a deficiency does exist. But this is not part of me: it pertains to my relationships with others. It is to do with the nature of my relationship with society: specifically with the type of society in which I was born and raised. Thus I see Asperger's syndrome as the inevitable deficiency in the relationship between any person with what I would term an Asperger's personality-type and the currently prevailing socio-economic zeitgeist.

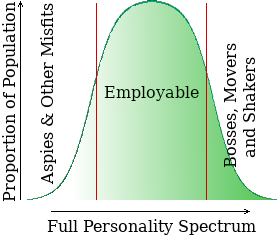

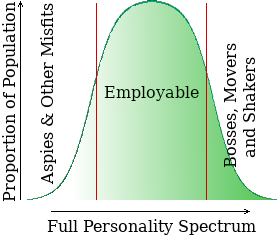

Thus, an Asperger's personality is simply a type of personality that just happens to be largely incompatible with the present western social order based on neo-liberal free-market capitalism. Notwithstanding, some people with this personality type do fare well under the present socio-economic system. They fall into niche jobs that thrive on their particular splinter-skills and way of being. But such is inevitably a result of a fortuitous occurrence within a natural lottery orchestrated by the complex dynamical behaviour of a socio-economy with the vast population of a modern nation. But if you don't happen, by pure chance, to find yourself in the right place at the right time with the right people in the right circumstances: you lose. This is the way of the neo-liberal free-market system. It bestows health, wealth and happiness upon the exigent, relegating the meek to misery and starvation, with a middle majority in a churning cauldron of economic uncertainty.

A socio-economy, governed by nothing other than the natural laws of complex dynamics, is red in tooth and claw. It renders government, nation and civilisation pointless. Is this the way it should be? I think not. Sentient man has a conscience, which, in the absence of indoctrination by tyrannical political regimes, would demand that he befriend and care for his fellows. It is for this reason that a social order, regulated by law, exists to compensate for the misfortunes of natural chance by helping those who, through no fault of their own, find themselves in need.

The capitalist neo-liberal free market system is a barrier, which separates common man from his natural means of turning his labour into his needs of life. Consequently, for the most part, common man can turn his labour into his needs of life only through an employer. An employer has the power to decide whether or not he will employ a person. Thus, collectively, employers have the power to decide whether or not a particular person shall be permitted to turn his labour into his needs of life.

Employers increasingly use personality tests to filter out all employment candidates who do not have what psychologists determine to be ideal employee personality types. I didn't, by taking thought, select the personality type with which nature endowed me. Consequently, it is not my fault that my personality is incompatible with the narrow modus operandi of the socio-economy within which I was born and am constrained to live. So is it fair and equitable that, because I was born with what psychologists decree to be the wrong personality-type for an employee, I should be forcibly denied the means to turn my labour into my needs of life? I think not.

Inset: Employers in the IT industry also increasingly use aptitude tests to filter out candidate employees that psychologists determine not to be apt for computer programming. I was an established programmer of merit 10 years before these tests came into vogue. Subsequently, when I applied for new jobs, I had to take an aptitude test. My average score was never more than about 5%. I could never see any connection between these tests [devised by psychologist] and programming computers. That is one of the reasons I started my own business. Customers didn't presume to present me with such ridiculous aptitude tests.

Personality Distribution

About 1 in 70 individuals are said to be on the autistic spectrum. Estimates seem fickle, but some sources put the proportion of people in the world with Asperger's syndrome at around ½%. It also seems that this proportion is increasing quite noticeably with time. Perhaps this is due to improvements in the fine-tuning of diagnostic tests. However, I suspect that the dominant cause is more likely to be the steady but relentless rightward shift of the incumbent socio-economic order, leaving an ever increasing proportion of the population outside its ever narrowing envelope of compatibility.

About 1 in 70 individuals are said to be on the autistic spectrum. Estimates seem fickle, but some sources put the proportion of people in the world with Asperger's syndrome at around ½%. It also seems that this proportion is increasing quite noticeably with time. Perhaps this is due to improvements in the fine-tuning of diagnostic tests. However, I suspect that the dominant cause is more likely to be the steady but relentless rightward shift of the incumbent socio-economic order, leaving an ever increasing proportion of the population outside its ever narrowing envelope of compatibility.

Society is thus becoming ever more exclusive; not only for aspies but for others too.

Obviously, there must exist some kind of natural bio-social mechanism, within each human individual, which, from inputs sensed from that individual's location within his social environment, determines which personality type, within the whole personality spectrum, his mind will automatically adopt. In other words, one's personality type is determined by one's unique position within time, space and the social order, according to the workings of the natural laws of sociological complex-dynamics.

What immediately intrigues me is the question of how small a sample of human population maintains this standard distribution of the full spectrum of personality-types. By intuition, I would wager that, in the absence of severe distortions resulting from the imposition of industrial capitalism and other individual and collective kinds of totalitarianism, the bell-curve distribution would be automatically maintained all the way down to the size of the natural anthropological community; namely, about 150 individuals.

Who Should Change?

My father was well aware that I didn't fit the mould of what he saw as a 'normal young lad'. I wasn't part of the 'local gang'. I didn't have many friends. I wasn't popular or respected. I didn't go off to the field to play football with the locals of my age. This frustrated my father greatly. I remember him shouting at me on many occasions: "Why don't you just muck in like everybody else?". He pressured me to change. He introduced me to the gregarious sons of his friends. But I simply could not connect. The unquestioned context was that I was the one who was abnormal. I was the one that didn't fit. Therefore, I was the one who should adapt. I was the one who should change and learn to fit in.

But I couldn't change. I did not have the innate abilities to enable me to do so. The necessary functionality simply wasn't there. My social ineptness stayed as my constant companion throughout my 'somewhat limited' working life. I was always self-motivated. I knew how to accomplish objectives and get things done. But not in the way the society in which I was trapped required me to operate.

Notwithstanding, I am merely one type within a vast bell-curve distribution of types that make up the purely natural human population. And there are millions like me. We are neither ill nor abnormal. We are just part of the natural distribution. And like any other types within the natural spectrum of human types of personality, we are all vital components of a balanced human population. We all have something essential to contribute to human society. Consequently, the onus cannot be on us to change what we are. On the contrary, there is a moral obligation upon society at large to take down the present rancid and dysfunctional system of law, government and commerce in order to replace it with a different one, which must be compatible with the full spread of natural human diversity.

Conclusion

A caring king or a benign dictator governs his people with equity. An evil king or a tyrannical dictator enslaves his people in misery. When each citizen of a democracy votes for policies that suit his own selfish ambitions, without concern for the catastrophic collateral effects those policies may have on some of his fellow citizens, then disparity will reign. For democracy to be fair and benign, each must vote for policies he truly believes will create conditions that are fair and satisfactory for everybody. And 1 in every 70 people, within the class called 'everybody', are like me. So clearly, people in general are voting selfishly, not socially.

However, it is not the political system, as such, that causes them to vote this way. The people can fare well or fare badly, irrespectively of whether they are governed by decree or by democracy. The fault is with the selfish character of who governs, be it the king or the people. Under modern western democracy, this selfish character is embedded within the public mind by the industrial elite who employ modern mass-media to constantly drip-feed the public with their own selfish attitudes, thus turning democracy into oligarchy. And it is this oligarchy that owns and controls all the resources of the planet, giving only to those for whom it currently has need, the means to turn their labour into their needs of life. This oligarchy thus owns and controls access to the tree of life, which it uses for its own selfish ends.

And this has resulted in the unmitigated socio-economic buggeration in which all of us are forced to try to maintain our miserable biological existences today.

Clearly, what is needed is a new social order of total inclusion in which those like myself, who are a little different, would — like everybody else — fare well, with the opportunity to contribute in accordance with their considerable abilities. It can be neither capitalist nor socialist. It is the subject of my book.

© 30 March 2020, 07 December 2024 Robert John Morton

These tests determined that I am between

These tests determined that I am between  About 1 in 70 individuals are said to be on the autistic spectrum. Estimates seem fickle, but some sources put the proportion of people in the world with Asperger's syndrome at around ½%. It also seems that this proportion is increasing quite noticeably with time. Perhaps this is due to improvements in the fine-tuning of diagnostic tests. However, I suspect that the dominant cause is more likely to be the steady but relentless rightward shift of the incumbent socio-economic order, leaving an ever increasing proportion of the population outside its ever narrowing envelope of compatibility.

About 1 in 70 individuals are said to be on the autistic spectrum. Estimates seem fickle, but some sources put the proportion of people in the world with Asperger's syndrome at around ½%. It also seems that this proportion is increasing quite noticeably with time. Perhaps this is due to improvements in the fine-tuning of diagnostic tests. However, I suspect that the dominant cause is more likely to be the steady but relentless rightward shift of the incumbent socio-economic order, leaving an ever increasing proportion of the population outside its ever narrowing envelope of compatibility.