Planet Earth is a beautiful and bounteous provider. Even now the planet's agriculture is producing more than enough food to keep everybody well fed and healthy. The poverty and starvation in the world is a consequence of politics, not production.

Mass: 5·98 × 10

21 tonnes

Radius: 6,371 kilometres

Area: 510 million km²

Ocean: 361·3 million km² (~70%)

Land: 148·8 million km² (~30%)

Habitable land: 130,693,000 km² (~26%)

Population: 6,000,000,000 (year 2000)

Habitable land per person: 21782·17 m²

Food production: 2671 kcal/person/day

NASA photo

It is my belief that, for a society to be fair, it must be based on a fair division of the only and ultimate means of turning one's labour into one's needs of life. And that only and ultimate means is land. If we were to divide the habitable land of the Earth — as it is currently being utilized — into imaginary landshares for all human beings alive today, each of us would have:

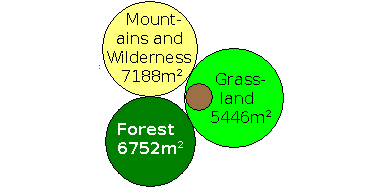

|

| Area m²

| Total

|

permanent

arable

| 170

| 170

|

other

arable

| 2226

| 2396

|

| grassland

| 5446

| 7842

|

| forest

| 6752

| 14594

|

| wilderness

| 7188

| 21782

|

A landshare is thus a substantial property. In today's world, the vast majority of mankind would have no hope of earning enough in a lifetime to be able to buy one — even on the most benevolent of mortgage contracts. If everybody is going to be able to own and use a landshare, it will have to be given to him. He will have to receive it as a free and undeserved gift. He will have to inherit it. It will have to be given to him as his unconditional birthright.

Only 1% of human food energy and 5% of protein consumption originates from fisheries and aquaculture. So pretty well all an individual's food requirements comes from his 2396 m² 'share' of the Earth's arable land. Of course, the geography and geology of the planet would not allow the whole of each person's landshare to be contiguous.

Dividing the Earth Fairly

In the second verse of my poem: Our Lost Inheritance, I address the question of fair division, when I ask:

But was this Earth given to all, or just the favoured few?

Why can we not all share it, with an equity that's true?

What exactly would be an equitable way for mankind to share the Earth among its multiple billions of individual inhabitants?

Over 8 billion [c 2020] sentient beings currently inhabit this planet. Each arrived here with nothing when he was born. Each will leave with nothing when he dies. Yet practically all of the Earth's 130,693,000 km² of habitable land is currently owned by members of a small minority. The majority own none of it. This is fundamentally absurd. Each human being, by self-evident right, should own his fair share of the planet on which he was born. But according to what moral criterion should it rightly be divided? There are two possibilities.

1) According to "Need"

The area of habitable land allocated to each individual could be based on the amount he needs in order to live and generate his needs of life. However, the very notion of need is highly subjective. It usually involves a decision by an elect few regarding what each of the vast majority needs in order to live. This begs the question as to what precisely is meant by "live". It can mean anything from merely sustaining basic biological existence to basking in the excess of the most opulent luxury. What quality of life is appropriate for the human inhabitant of Planet Earth? And who is qualified to decide? This perceived appropriate quality of life will obviously vary according to individual opinion among the decision-makers, who invariably will not be subject to their own decisions. I do not think this is fair.

2) According to Availability

I prefer a régime in which each human being on the planet owns his fair share of what is available. This way, nature has already made the decision for us. There are about 130,693,000 km² of habitable land on the Earth. If we divide this among its 6 billion current [year 2000] inhabitants, we find that there are 21,782 m² [square metres] of habitable land per person. I therefore believe that, by right of birth, every human being that is alive on this planet rightfully owns 21,782 m² of its habitable surface. I refer to this fair share of the habitable surface of the planet as a person's landshare. Others may think of it as his available ecological footprint.

It is not practical to divide all the planet's habitable land surface into 6 billion geometric lots. Not all terrain lends itself to regular division. All four land-types are not spread homogeneously across the planet. Consequently, any particular 2-hectare area is very unlikely to contain mountains, forest, grassland and arable all together. Hence, a person's landshare cannot always be a contiguous piece of the Earth's surface. For example, its mountainous and forest fraction may have to be located separately from its grassland and arable portions.

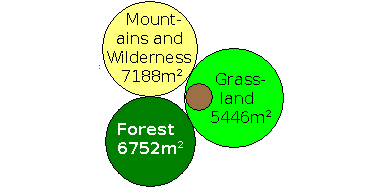

A person's landshare would therefore comprise one contiguous lot of 5446m² of arable and grassland, another contiguous 6752m² of forest and a third contiguous area of 7188m² in the mountains. It may even be necessary in some cases to fragment these three areas to regions of different land-type. Far from being an imposition, fragmenting a person's landshare gives him the opportunity for a complete change of scenery within his own property.

The nature of the human life-form constrains it to live in families. It is not practical for the members of a family to have their personal landshares geographically separated from each other. The landshares of all the members of a family must therefore be concatenated into a single contiguous physical gleba. The area of a gleba is thus proportional to the number of people in the family.

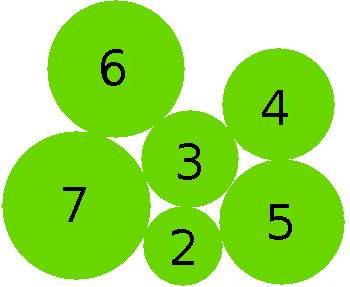

Families vary in size. So let us consider, for example, the dimensions of a gleba for a generic family comprising 2 grandparents, 2 parents and 3 children, forming one productive family unit of 7 human beings. We can regard the combined area of land available to this family to be 7 times the 21,782 m²/person that the planetary statistics provide for each human being. That works out at 152,475m² (or just over 15 hectares = almost 37 acres) for this family. Of course this is not all land on which they can grow food. It is made up as follows:

This family gleba thus comprises 1·7 hectares of crops, 3·7 hectares of grass, 4·7 hectares of forest and 5·1 hectares of wilderness. You can imagine this as a circle of land just over 220 metres radius with a large family house plus outbuildings in the middle.

On average, over the entire planet, this land currently produces 2,671 kilo-calories per person per day. This is equivalent to a steady 129 watts. That is almost 30% more than the minimum 2,073 kilo-calories per day — or 100 watts — required by the human body. Thus, this planet currently produces 30% more food than is needed to eradicate malnourishment and starvation.

A vast amount of renewable energy is harvestable annually from the trees of the forest. Only about 8,000 m² of managed forest would be required to provide the 8,000 kg of naturally dried wood (24% moisture) to provide the 22½MWh (81,000 megajoules) a year to heat my home and the 3½ MWh (12,600 megajoules) of electricity it uses. That is a patch of forest only 90 metres square. As well as being a superb fuel, wood is also the best material there is for building a home and making furniture. With 4·7 hectares of woodland, this family would always have plenty of wood for both fuel and material.

Beneath this family's generic 15·2 hectares of the Earth's surface lie all the materials necessary to support all the products and devices of modern technology. So if, as would seem fair, minerals were deemed to belong to the owner of the land beneath which they lay, then everybody would have an unconditional share in every technology that used them. Then there is the sea. Most of the planet is covered by sea. Some of the world's food comes from the sea. There are 6 hectares of sea for every human being on earth. That is 42 hectares for our sample family unit of 7 people.

Their gleba thus equips this family to be able — under their own initiative — to turn their work into their needs of life. But the gleba also provides them with bonuses other than economic ones. It provides a healthy natural environment, rich in what facilitates good physical and intellectual development as well as rest and recreation. It gives them the means of learning about nature and appreciating its beauty; thus providing them with the framework of language, thought and communication. It inspires them to invent technologies and express themselves through art. It gives them a place to entertain the traveller and play host to friends.

To make best use of their land (and indeed their sea), from a holistic point of view, it is expedient for the family not to insist on occupying the whole of their 15·2 hectares of the planet's surface as one contiguous plot. It is better for them to put at least some of it to integrated productive use. Nevertheless, they must still own it. And as its owners they always have a right to a portion of any economic yield gained from it.

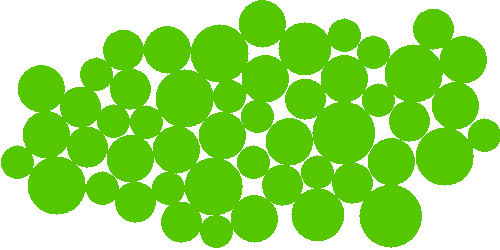

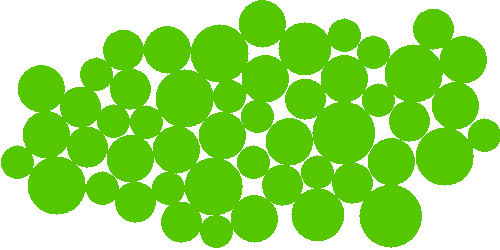

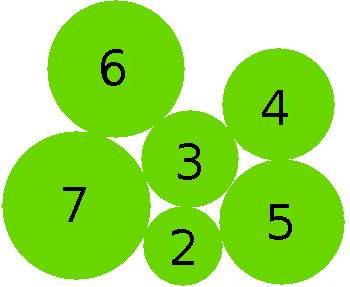

Of course, not all nuclear families are the same size. So glebas must vary in size according to the numbers of people in the families that occupy them. The green circles represent glebas. The area of each is proportional to the indicated number of people in the family that occupies it.

In a grasslands region, each circle represents the grassland and arable part of a family's gleba. In a forest region, each circle represents the forest part of the family's gleba. In a mountain or wilderness region, each circle represents the mountain and wilderness part of the family's gleba. In areas where grass and forest naturally co-exist, each circle represents the contiguous forest, grassland and arable parts of a family's gleba. Which parts are combined into contiguous areas and which are separated depends on the relief of the region in which a particular gleba is located.

Of course, not all nuclear families are the same size. So glebas must vary in size according to the numbers of people in the families that occupy them. The green circles represent glebas. The area of each is proportional to the indicated number of people in the family that occupies it.

In a grasslands region, each circle represents the grassland and arable part of a family's gleba. In a forest region, each circle represents the forest part of the family's gleba. In a mountain or wilderness region, each circle represents the mountain and wilderness part of the family's gleba. In areas where grass and forest naturally co-exist, each circle represents the contiguous forest, grassland and arable parts of a family's gleba. Which parts are combined into contiguous areas and which are separated depends on the relief of the region in which a particular gleba is located.

The Geometry of Division

In the United Kingdom, the land is divided into an almost continuous quilt of little irregularly-shaped fields. Their shapes seem to have been determined solely by where neighbours finally agreed that the dividing fences should be. There is very little land that is not a field. Nature has little sanctuary. In some places, roads follow the contours of the landscape. In others, they wind around awkward bends that are there for no reason other than to avoid encroaching into the odd-shaped fields.

In other countries, land seems to be divided in a more orderly and geometrical way. The vast fields seem to be much more rectangular. This allows roads to be straight. The result is a gridiron countryside that has the boring regularity of an American city. Again, nature has little space in which to be free of human touch.

When I used to walk the countryside with school friends in my teens, I never liked the way all the land was divided into fields. It left us with no place to wander freely across the land. We were confined to dodging traffic on country roads or battling through impenetrable thickets called country footpaths. Farmers invariably blocked country footpaths with barbed wire fences. This led me to ponder at great length how, in my vision of an ideal world, land should be divided and used by mankind.

In the context of the personal landshare, I imagined all the habitable land of the Earth divided into tiny 2-hectare units. These, I thought, could be concatenated to form family-sized glebas. But what shape should this standard division be? The ideal, I thought, would be a circle. The problem with circles, though, is that they don't tessellate: when you try to put them together, space is inevitably "wasted" in between them. So, in my early thoughts, I immediately dismissed the circle as the ideal shape for a gleba.

I thought that tessellation (the ability to fit together without leaving any space in between) was the primary necessity for the ideal shape of a gleba. I considered the square. But you can only form a bigger square with 4 smaller ones. The shape of a gleba for a family of 2, 3, 5, 6 or 7 would therefore be very awkward and irregular.

So then I considered the 1:√2 rectangle. This shape has the property that if you halve it or double it, you get smaller and larger areas of exactly the same shape. That is why standard A4 paper is the shape that it is. But this would still yield odd shapes for glebas 3, 5 or 7 times the unit size. It also suffers from the same problem as the square as regards roads. It would result in a connecting road system that had the form of a right-angled grid. Boring, with a right-angled cross-roads: the most dangerous form of road junction.

I then considered making the landshare an equilateral triangle. They tessellate. However, you still get a variety of odd shapes when joining them together to form family-sized glebas. It also results in a road network in which each junction has 6 ways. which is extremely difficult and even more dangerous than cross-roads.

Lastly, I considered the final regular shape that tessellates, namely the hexagon. This seemed much more promising because it is the shape that most approximates to a circle — my ideal shape for a landshare. This provides a more benign form of road network at which all junctions have only 3 ways. But it only works well for glebas of 1, 3 or 7 units. In any case, any road journey would be punctuated by a 60° turn every 44 metres. This is not very practical.

Lastly, I considered the final regular shape that tessellates, namely the hexagon. This seemed much more promising because it is the shape that most approximates to a circle — my ideal shape for a landshare. This provides a more benign form of road network at which all junctions have only 3 ways. But it only works well for glebas of 1, 3 or 7 units. In any case, any road journey would be punctuated by a 60° turn every 44 metres. This is not very practical.

There did not seem to be a regular shape for a landshare that would tessellate to form glebas (comprising 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, ... landshares) of the same regular shape that would each tessellate with all its neighbours.

Having lived most of my life in South-east England, the idea of one field being separated from the next by nothing more than a hedge or a fence had been indelibly burned into my mind. It just seemed natural and unquestionable. Since moving to Brazil, however, I began to question this notion. Why should land be divided completely into lots and fields, with no free space for undisturbed nature?

Perhaps a non-tessellating shape like the circle was better for a gleba. Perhaps a shape with the property of non-tessellation was preferable. A non-tessellating shape for a gleba guarantees the existence of "waste" space in between adjacent glebas, within which nature can flourish undisturbed. This seemed to be a much better idea.

My original idea had been that the habitable land of Planet Earth should be divided into unit landshares. This way, every human being could possess and occupy his rightful share of the planet on which he was born. But then I began to think deeply about land. I pondered the patchwork quilt of the British countryside. I marvelled at the open deserts of Nevada and Southern Utah. I admired the tranquillity of the rolling mountains of Minas Gerais. I looked in awe at the rich vastness of the plains of Goias. These all seemed to be telling me one thing. They did not belong to man. They were, on the contrary, his mother. And a man does not own his mother.

I have empathy for the Russian perception of their land personified as Мать-Росси́я [Mother-Russia] a mother goddess мокошь [Mokosh] who sustains her children by providing their needs.

On the other hand, a city apartment or a house on a suburban lot is not an ideal environment for humans. We need open space. We need proximity to nature. We need peace and tranquillity. We need separation as well as socialization. Notwithstanding, we do not need to be the sovereign owners of a piece of land, put a fence around it and exclude others from it in order to walk on it, enjoy it, benefit from it, live on it and gain our needs of life from it. We simply need the space around us and the freedom and duty to use it sustainably.

In my endeavour to find a suitable way to share the Earth's habitable surface I decided to look at how nature divides space. And what sprung to mind was the way the molecules of a gas share space. They tend to distribute themselves evenly throughout the total space available. But not exactly evenly. And not statically. The space 'occupied' by a single molecule moves location and varies dynamically between a maximum and minimum size that are not too extreme. A few elite 'wealthy' molecules don't commandeer for themselves the vast majority of all the available space, forcing the vast majority of common 'poor' molecules to bunch tightly into 'suburban' conglomerations. In other words, each molecule occupies its mean free space: a somewhat flexible volume of space, which meanders continually throughout the whole. It is like a nomad who takes, along with him on his travels, his own fair share of allodial hinterland through which he may always, directly and immediately, turn his labour into his needs of life.

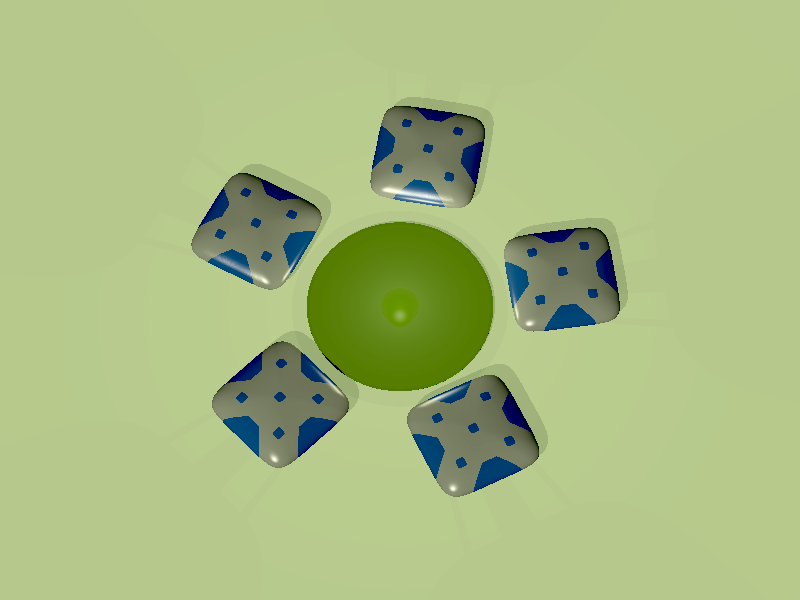

So what we each need is our own piece of mean free space. Suppose all the human inhabitants of the Earth were spread out evenly over its habitable surface, as typified on the left for the UK. Each of us would find himself in the middle of his own 2 hectares of mean free space. If circles could tessellate to fill the spherical surface of the Earth, then each of us would be at the centre of a circle of just under 80 metres radius. We would each be 160 metres from each of our neighbours.

So what we each need is our own piece of mean free space. Suppose all the human inhabitants of the Earth were spread out evenly over its habitable surface, as typified on the left for the UK. Each of us would find himself in the middle of his own 2 hectares of mean free space. If circles could tessellate to fill the spherical surface of the Earth, then each of us would be at the centre of a circle of just under 80 metres radius. We would each be 160 metres from each of our neighbours.

But circles don't tessellate on the surface of the planet. Even if they all touched, there would always be some space "wasted" between them. We must therefore choose a radius that is somewhat less than that corresponding to the complete 2-hectare individual share of the habitable land surface of the planet. Suppose we adopt a benevolent attitude to nature. Let us each give up half of his 2-hectare theoretical landshare. Let us each just claim 1 hectare. This would leave each of us with a circle of land of just over 60 metres radius. This we can regard as our rightful mean free space, or universal landshare.

Need For Flexibility

But how can this space be allocated fairly? The straight geometric division into family glebas of (2·1 hectares) × (the number of individuals in the family) is not necessarily a fair way to divide land. This is because, unfortunately, the fertility of land is not the same throughout the various continents and islands of the Earth. Some land is located in nice places, other land is located in horrible places. Some land is fertile, other land is barren.

Consequently, the productive potential of land varies enormously over the habitable surface of the planet. Neither is rainfall and sunshine uniformly distributed. The quantities and types of minerals also vary from place to place. So climate, fertility, water and other resources vary with location.

In some places, one hectare of land per person will yield far more than he needs. In other places, it may not even yield enough for him to survive. Dividing the planet's surface into fixed areas is not therefore a fair way of sharing it out among its inheritors. Some measure of quality must be factored into the calculation. This means that to make the division of land as fair as possible, a variable unit of measure must be used. The area of a landshare must therefore vary according to where it is located.

This idea has a precedent. In the past, land was measured in acres, alqueires and all kinds of other irrational units. Nowadays land is measured in standard metric hectares. Each of these units of measurement represents a fixed physical area of land. However, in ancient times in England, land was measured in a variable unit called the hide.

The Ancient Hide

The hide was the amount of land deemed necessary for a family to support and sustain itself. But it was not a unit of constant area. Its area varied according to the fertility of the land concerned. A hide was smaller for rich land than it was for poor land. Its size was also affected by the topography of the land and the climate in which it lay. It was a unit of equal productivity or yield. Thus if the productive land surface of the Earth were divided into hides, their sizes would vary considerably from one part of the Earth to another, and perhaps even from one time to another.

The hide of land thus made a family economically independent. It enabled them to transform their own labour directly into their own needs. And they could do this entirely on their own initiative and under their own control. Their survival and well being didn't depend on a corporate master having an on-going requirement for their labour. Their basic needs were assured.

The hide of land thus made a family economically independent. It enabled them to transform their own labour directly into their own needs. And they could do this entirely on their own initiative and under their own control. Their survival and well being didn't depend on a corporate master having an on-going requirement for their labour. Their basic needs were assured.

Consequently, a family with a hide of land could never be held to ransom to sell its labour for a wage that could barely keep them fed and clothed. Their survival and well-being could never be jeopardised by the ravages of fickle and dispassionate market forces.

Contrary to what the inhabitant of a modern free-market economy may suppose, an established hide of land does not demand that we spend the best part of all our days locked in hard toil in order for it to yield to us the needs of life. There is plenty of prime time left in the course of a year for the pursuit of other things. A hide of land allows its owners the time and the means to be artisans as well as farmers. It enables them to become scientists, designers, engineers, artists and philosophers as well as workers. It empowers them to become educators as well as parents.

I therefore believe the ancient hide of land to be the ideal principle on which to define a landshare for the future world of which I speak.

NOTE: the English hide is not the only variable measure of land. There is an old Brazilian measure called the alqueire. This also varies from place to place according to soil quality and climate. It was defined as the area of land required to grow one standard mule train of cereal crop. The modern official measure for rural land in Brazil is the módulo rural. This is the amount a family requires in order to provide its own needs. It is also the minimum amount of rural land that can be traded. Where I live it is currently set to 20,000 m² [~5 acres]. In other places it is different.

The size of a landshare must therefore expand or shrink according to such variable quality factors as fertility, abundance of water, benevolence of climate and undulation of terrain. We may think of the landshare as having an area, a, that has a regional variability centred around a median of 1 hectare. The value of a for different regions would have to be decided by global consensus. With this arrangement, each of our circles of freedom should fit within the Earth's habitable land areas without overlapping, and in many cases, without even touching.

Until the human population of the planet stabilizes, it will be necessary, from time to time, to adjust the value of a. New glebas would then be allocated as multiples of this revised area of a landshare.

Most people live in family units, or at least share a home. Each allocation of mean free space therefore needs to be of an area A = n × a, where n is the number of people living together within this mean free space or gleba as a family or simply as a sharing. Personal landshares that make up a physical gleba do not have distinct or separate existence within the area of the gleba. No individual family member can go to a specific part of the gleba and declare "This is my bit!". His landshare is merely an abstract amount of land within the gleba. The gleba is thus an area of land that is collectively owned by all the members of the family.

Allocation of Land

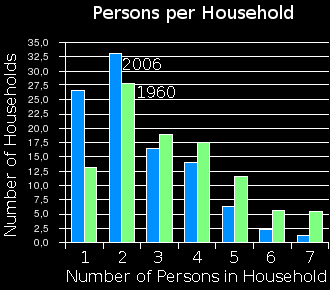

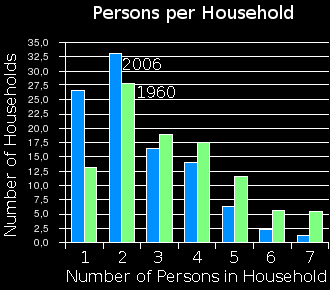

The chart on the right is derived from figures from the U.S. Census Bureau. It shows the percentages of homes comprising 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7+ individuals in the United States of America in 2006 & 1960. Clearly, households are getting smaller, with more and more people living alone. I think this is a symptom of the growing dysfunction of present-day society. I do not think it would be this way in a more ideal world where people could live in their own mean free space without the unnatural stress imposed by modern life-styles.

The chart on the right is derived from figures from the U.S. Census Bureau. It shows the percentages of homes comprising 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7+ individuals in the United States of America in 2006 & 1960. Clearly, households are getting smaller, with more and more people living alone. I think this is a symptom of the growing dysfunction of present-day society. I do not think it would be this way in a more ideal world where people could live in their own mean free space without the unnatural stress imposed by modern life-styles.

In a world where each had an inalienable right by birth to 1 hectare of mean free space, I think people would opt to live in larger groups. I do not think so many people would opt to live alone. Rather, I think that most would live in 2 and 4-person units. The gleba landscape would therefore comprise a mixed distribution of sizes. The relative abundance of each size would be proportional to the distribution of family sizes.

Note the occurrence of "waste" space between the circles. These apparently wasted areas are left entirely to nature. Further space may also be wasted between circles to allow them to be located sensibly with respect to the topology of the land. For example, space should be left to allow a river to meander freely within its own "mean free space". Similar free space should be left for roads.

Whenever a new gleba is required, it is allocated from a regional pool of spare habitable land. A computer program can be used to allocate the required gleba according to a "best fit" algorithm. This would take full account of land topology, rivers and roads.

The system of roads that connects glebas with each other, and with the rest of the world, should have the natural form of a river with its myriad tributaries. They should follow the contours of the terrain harmoniously. Roads can conveniently meander around the circular glebas within the intervening "waste" space. In some places there may be insufficient "waste" space between the circles. In this case, each gleba could be set within a slightly larger circle, thus surrounding it with a rim of "public" space. This would allow the roads to follow a straighter path.

Taking this idea a stage further, perhaps it would be better to map out the road system first. This should follow the natural lie of the land, taking the form of a river and its tributaries or a tree and its branches. Each junction, or branch point, would thus have the simple safe form of a 'Y'. Family glebas would then be the leaves on the branches or the springs of the tributaries.

An optimum number of 5 to 7 glebas can form an egalitarian group with each home offset from the centre of its gleba towards its fellow homes in the other glebas of the group. The picture below suggests a way in which UTDs could be grouped for a multi-generation family or a group of close friends.

The 7 UTDs are 45° apart around a circle, each with its gleba of land extending outwards behind it. This leaves space for an access road for all 7 UTDs. The roads, of course don't have to be so geometrical. They can be more curvy to suit the lie of the land. Groups, in turn, can be optimumly agglomerated into cohesive communities of 7 groups totalling around 50 homes. Somewhere within the community of 50 there would be a community centre, perhaps in the form of a vast geodesic dome.

People should be free to move around on their planet and choose where they want to live. The only constraints should be practical ones such as the current availability of a spare gleba of the appropriate size within the region they desire. For this purpose, an efficient automated global land registry is necessary.

Children are born. Old people die. Thus families change in size from time to time. When a family gains or loses a member, it moves to a new or spare gleba of the appropriate size. Such a change is not only beneficial from the point of view of having adequate space and resources. A change of location and environment is also beneficial psychologically and educationally. It heralds a new phase of the family's life.

A couple live in their 2-unit gleba. They then have a baby (John). John, by right of birth, immediately inherits his new landshare. To facilitate this, the family of 3 moves to a new 3-unit gleba. Later, they have a second baby (Mary). Mary, by right of birth, immediately inherits her landshare. To facilitate this, the family of 4 moves to a new 4-unit gleba. Years pass. John and Mary both grow to become adults. They each find a mate, leave their parents' home and each new couple is allocated a new 2-unit gleba. Their parents now move to a 2-unit gleba again. More years pass. Their parents die. As each parent dies, his or her landshare becomes part of the universal land pool. A surviving parent then either moves to a one-unit gleba or becomes an additional "landshare holder" in a larger gleba with the family of one of his children.

A Universal Birthright

A landshare is the universal birthright of every human being born on this planet. That right is effective from birth. Consequently, when a new baby is born into a family, that family moves to a larger gleba. The family's new gleba is thus one landshare larger than their old one. This means that, a birthright landshare is not a fixed or particular piece of land in a fixed or particular location. It can, at one time, be part of one physical gleba, while later becoming part of another physical gleba of a different size.

A landshare is thus an abstraction. It is an abstract unit area within a real physical gleba. So if a member of a couple decides to move or separate, he exchanges his personal landshare for a personal landshare within another physical gleba.

People should be able to exchange personal landshares around the world as a separate universal currency. Exchange should be smooth and instantaneous, once a decision to move has been made and agreed. Nobody should ever be rendered immobile by economic or political constraint. To make mobility easy, people should adopt a mentality that is more nomadic. We should not become too attached or rooted to a particular place. For this purpose, homes should ideally be vehicular — or at least transportable. The kind of homes I imagine would require future sustainable technologies, but I think these are not too far away.

This philosophy of land allocation is based on birthright: not need. It is based on one's rightful share of the planet. This is hopefully much larger than the amount of land necessary merely to provide one's needs. Consequently, a family's gleba should be more than ample to provide them with plenty.

Source of Knowledge

It is important to realise that the basic knowledge and understanding on which proper specialised skills can be built can only come from nature.

If I had never swung on a rope tied to a tree branch when I was young then I would never have been able to visualise and fully understand the pendulum. If I had never understood the periodic motion of a pendulum I may never have grasped the mathematics of differential equations. If I had never watched a leaf floating down a stream after a heavy rain and pondered the various ways it translated and rotated as it moved, I may never have grasped the physical concepts behind vector analysis. If I had never seen the seasonal changes in water pouring over a waterfall, I may not have perceived the true relevance of the exponential constant. If I had never seen clouds drifting and swirling on the south-west wind, I may never have grasped the rudiments of complex dynamical systems.

I am sure there are countless examples in every specialist discipline which illustrate how the understanding of its fundamental concepts is firmly rooted in one's formative personal experience of natural phenomena.

I was lucky. As a child I lived close to the old wild scrub-covered slag heap of a disused coal mine. Adjoining the grounds of my school was a stretch of natural woodland which was part of an old aristocratic estate. During the lunch hour we would go into the woods and play on a rope which was hung from the branch of an oak tree over a stream. It was the most beautiful place I knew, carpeted with crocuses in the Spring as far as the eye could see. Then there were the holidays to North Wales and the Lake District where I was exposed to the beauty of the mountains.

Yet in all this, I was not much more than an observer. I was never able to use the land. I never had the chance to work with nature. I never had the opportunity to marshal its resources for the production of food and materials. If I had, I think I would have been much the wiser for it. I am convinced that the ability to understand the basic concepts and notions of even the most abstract areas of science and mathematics must come ultimately from one's formative experiences of the natural environment.

Whenever I come across a concept I cannot grasp, I feel sure that it is because I have missed an opportunity to observe and experience some natural phenomenon. I am sad for the many poverty-bound children of Britain today who are deprived of this formative exposure to nature.

Crucible For Talents

Nobody is good at everything. Each human ability is not present to the same extent in everybody. One individual is good at some things while a different individual is good at others. The wide variation in the degree to which each special ability or talent is present in any given individual gives each of us our somewhat unique aptitude profile.

Hands-on use of the family's gleba to produce the needs of life provides the ideal circumstances within which one's natural aptitudes and talents can develop. It provides those formative experiences on which a firm understanding of science, engineering, economics and even life itself can be built through formal education. The acquired knowledge and skills resulting from this process can then be used to sustain a technology-based specialist artisanry within which innovation and sound engineering may flourish to the benefit of all.

Unfortunately, modern capitalist economics imposes upon us a wholly unnatural degree of specialisation. This is far too narrow and stifling to provide the individual with anything approaching an acceptable level of intellectual fulfilment or quality of life. How often have I eavesdropped on canteen conversations in which highly qualified engineers, scientists and managers have been expressing their idyllic dreams of living in the country on their own working small-holding while continuing also with their specialist work remotely, meeting only when necessary?

The indelible presence of this back-to-nature dimension in the universal human dream suggests that, as well as possessing each his own special talents, there are, lying dormant within each of us, those general abilities which enable us to extract our basic needs from nature. Indeed it seems that true human fulfilment can be achieved only by exercising both.

Unlike our modern capitalist market economy, a landshare-based economy would not only exercise one's general abilities to extract one's needs of life from nature, but also provide the space, resources and opportunity to develop and exercise one's natural specialised talents. So, while being self-sufficient in the basic needs of life, one could, at the same time, also be an artisan providing a particular specialised product or service both for one's own use and to sell on to others through a truly free market system.

Parent Document |

© Dec 1996, Feb 2004, Jul 2007, Aug 2012 Robert John Morton

Of course, not all nuclear families are the same size. So glebas must vary in size according to the numbers of people in the families that occupy them. The green circles represent glebas. The area of each is proportional to the indicated number of people in the family that occupies it.

In a grasslands region, each circle represents the grassland and arable part of a family's gleba. In a forest region, each circle represents the forest part of the family's gleba. In a mountain or wilderness region, each circle represents the mountain and wilderness part of the family's gleba. In areas where grass and forest naturally co-exist, each circle represents the contiguous forest, grassland and arable parts of a family's gleba. Which parts are combined into contiguous areas and which are separated depends on the relief of the region in which a particular gleba is located.

Of course, not all nuclear families are the same size. So glebas must vary in size according to the numbers of people in the families that occupy them. The green circles represent glebas. The area of each is proportional to the indicated number of people in the family that occupies it.

In a grasslands region, each circle represents the grassland and arable part of a family's gleba. In a forest region, each circle represents the forest part of the family's gleba. In a mountain or wilderness region, each circle represents the mountain and wilderness part of the family's gleba. In areas where grass and forest naturally co-exist, each circle represents the contiguous forest, grassland and arable parts of a family's gleba. Which parts are combined into contiguous areas and which are separated depends on the relief of the region in which a particular gleba is located.

Lastly, I considered the final regular shape that tessellates, namely the hexagon. This seemed much more promising because it is the shape that most approximates to a circle — my ideal shape for a landshare. This provides a more benign form of road network at which all junctions have only 3 ways. But it only works well for glebas of 1, 3 or 7 units. In any case, any road journey would be punctuated by a 60° turn every 44 metres. This is not very practical.

Lastly, I considered the final regular shape that tessellates, namely the hexagon. This seemed much more promising because it is the shape that most approximates to a circle — my ideal shape for a landshare. This provides a more benign form of road network at which all junctions have only 3 ways. But it only works well for glebas of 1, 3 or 7 units. In any case, any road journey would be punctuated by a 60° turn every 44 metres. This is not very practical.

So what we each need is our own piece of mean free space. Suppose all the human inhabitants of the Earth were spread out evenly over its habitable surface, as typified on the left for the UK. Each of us would find himself in the middle of his own 2 hectares of mean free space. If circles could tessellate to fill the spherical surface of the Earth, then each of us would be at the centre of a circle of just under 80 metres radius. We would each be 160 metres from each of our neighbours.

So what we each need is our own piece of mean free space. Suppose all the human inhabitants of the Earth were spread out evenly over its habitable surface, as typified on the left for the UK. Each of us would find himself in the middle of his own 2 hectares of mean free space. If circles could tessellate to fill the spherical surface of the Earth, then each of us would be at the centre of a circle of just under 80 metres radius. We would each be 160 metres from each of our neighbours.

The hide of land thus made a family economically independent. It enabled them to transform their own labour directly into their own needs. And they could do this entirely on their own initiative and under their own control. Their survival and well being didn't depend on a corporate master having an on-going requirement for their labour. Their basic needs were assured.

The hide of land thus made a family economically independent. It enabled them to transform their own labour directly into their own needs. And they could do this entirely on their own initiative and under their own control. Their survival and well being didn't depend on a corporate master having an on-going requirement for their labour. Their basic needs were assured.

The chart on the right is derived from figures from the

The chart on the right is derived from figures from the