I know a farmer who has 158 hectares [390 acres] of fertile English countryside. Through his knowledge, he uses it to turn his work into the most fundamental human need: food. And not just for himself. With his 158 hectares, he grows far more food than he needs for his own family. He has plenty to sell to others.

I know a farmer who has 158 hectares [390 acres] of fertile English countryside. Through his knowledge, he uses it to turn his work into the most fundamental human need: food. And not just for himself. With his 158 hectares, he grows far more food than he needs for his own family. He has plenty to sell to others.

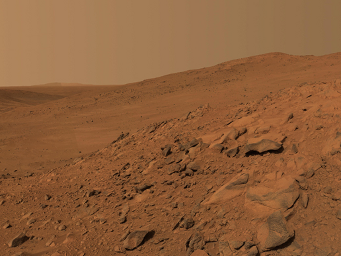

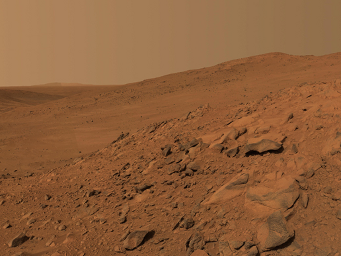

But suppose we were to transport our farmer to a barren planet. Here, in the place of his fertile land, he is bequeathed 158 hectares of lifeless sand and rock like the piece of the Martian surface shown on the right. With this, neither his lifetime of acquired knowledge nor any amount of hard work will produce even one morsel of food. Within a very short time, he and his family would starve to death. He needs the fertile land. Without it, his knowledge and hard work are worthless.

Our farmer did not make his land. He did not design the ear of barley or the fully automated walking food and clothing factory we call a sheep. He did not write the DNA programs that expedite their development. He does not supply the materials and energy of which they are made. He does not fashion and build them with his hands. He does not uphold the biochemical laws that sustain the complex processes within them. It is not the farmer's hard work that produces his needs of life. His work is simply a minor, but necessary, condition to acquiring them for himself.

Therefore, if during his stay on this earth, our farmer is going to achieve anything, he has first to be given the means of turning his work into his needs of life. He has somehow to be given his land. No matter what man-made deed, mortgage or other legal and fiscal paraphernalia is involved in acquiring his land, the underpinning principle is plain, simple and universal: our farmer arrived on this planet with nothing. He will depart from it with nothing.

He needs land. But since he arrived on this planet with nothing, he had nothing with which to buy any land. And since he could not create it from nothing, whatever land he comes to possess has necessarily to be a gift. When he leaves this planet, he cannot take his land with him. It has to remain part of the planet's surface. There is therefore no point in his exchanging it for something else because he cannot take anything at all with him.

Possession of land and property is therefore as temporary as life itself. It is a transitory 'Right of Usage' to which is attached the moral obligation of responsible stewardship. Our farmer acknowledges this obligation of stewardship. As I often hear him say: "You must live as though you'll die tomorrow, but farm as though you'll live forever."

The only means of transforming human labour into human needs are the agricultural, mineral and energy resources of the Earth's surface and biosphere. Anybody whom society denies use of these means is, in effect, marooned on a barren planet, visited only occasionally by the 'space shuttle' of State welfare, which delivers to him his meagre rations of survival.

Parent Document |

©November 1994 Robert John Morton

I know a

I know a