Ch08: Footnotes

Currency of Land

Unfair Division

Land, Work, Needs

Conscience requires each to divide what he has fairly among his children. But the rich have no conscience. How else could they be rich in a world of poverty? Apathy, negligence, ignorance and pressure cause them to divide what they have unfairly, keeping wealth in the hands of the favoured few.

I know a farmer. He farms 1·58 km² of beautiful English countryside. It includes a large 400 year old farm house in a farm yard with extensive buildings, a detached cottage near the farm house and a secluded terrace of 3 cottages about ¾ km from the farm house. [This farmer died in 1996. But his farm is still very much the same as it was — a mixed farm raising cereals and sheep.]

He had a bad start. His father — also a farmer — had a large farm with its own water mill. Sadly, his father died when he was 14, and his brother, who was much older, took the farm and cut him off with nothing. He worked hard for other farmers for a while. He gained a good reputation. Later he rented odd fields which he farmed himself. When eventually he married in his thirties he rented a small farm in a fairly isolated Kent village. Then, shortly after his marriage, his fortunes began to change.

A fortuitous circumstance occurred. A large estate nearby came onto the market. The aristocratic owner was in financial trouble. He had to sell. It was the mid 1930's. It was not a seller's market. The estate included a number of farms. They were all run down. Their buildings were in need of much repair. They had no sanitation or mains water.

Our farmer finally found himself in the right place at the right time. One of the farms on offer was exactly what he had always wanted. It was on good fertile chalk land. Most of it was on an easily workable flat plateau, but it also included one side of one of its bounding valleys which offered shelter for sheep in winter. There were vast open fields, an orchard, and quite a bit of woodland for winter fuel and fence posts. This particular farm was being offered for £2,000. Having at that time only £20 to his name, our farmer went to visit his bank manager. Unlike today, his bank manager actually said 'yes'. Thus now, for the first time in his life, our farmer had a farm of his own.

He laid on mains water and sanitation to the farm house and cottages. He also piped water to sheep troughs in his fields. Then came World War II. Demand for home produced food was insatiable. He began to prosper. He paid off his original bank loan and was later able to buy up adjacent packets of land as they came on to the market. He was thus able to build up his farm to the 158 hectares it covers today.

This farmer has 6 children — 3 boys and 3 girls. Two of the boys and two of the girls married. One boy and one girl did not.

His eldest son is a farmer born and bred. He specialises in sheep. He is about 60 years old (1999). He has never married. He plays the organ at his local village church. He lives in a private world that seems out of place in present-day mainstream society. It is a world which most would relegate to the past. A cliquish world of narrowly opinionated farming types. It is a world dominated by sheep shows and fox hunting. Nevertheless, within his particular culture, he does have a wide personal coterie of friends and other contacts through which he is able to attain social fulfilment and successfully ply his trade. He is kind-hearted, confident and has an assertiveness which is tempered to a degree by his moral standards. But he comes across to me as one who 'knows all there is to know about absolutely everything' and has a sassy, hyper-critical disposition.

His eldest daughter was once a happy girl, full of zest. She was eager to please both her parents and live up to their expectations. She over-worked at school and consequently suffered a nervous breakdown from which she initially recovered. Unfortunately, after she married in 1967, it became a recurring mental illness which denied her the career she had wanted. Her illness also limited her husband's options for developing his career. She has thus never been able to earn her own living. She is loving, kind, and is dedicated to her family. The drugs she has to take to control her illness make her slower than most people both mentally and physically. This induces within her a severe lack of confidence and makes her shy and unassertive. Nevertheless, she uses her abilities to the full, caring for her husband and three children. She is happy. She never complains.

His second daughter never married. She seems to have been scarred by an event early in her life which left her with a big chip on her shoulder. She first trained and worked as a personal assistant to a company director. However, she was never happy in this role. Her first love was always the countryside. She soon returned to the farm house where she has spent most of her life earning pin money fruit-picking at neighbouring farms. As her father has become old, she cares for him. She is a private person, but she is genuine — what you see is what you get. Sadly, her experiences in early life robbed her of her confidence, leaving her unassertive and open to easy domination. She comes across to me as nice on the surface, but unpredictably very nasty and treacherous.

His second son is also a born and bred farmer, but of a very different ilk. He is in tune with modern society. He is commercially street-wise. He has lots of trade contacts both in farming and in transport and other casual contract jobbing markets. He is a shrewd competent trader. He knows how to wheel a deal. He is ambitious and confident to the extent of appearing a little cocky. I think he can also be devious if and when it suits his ends. He married a 'gold digger'. She wants and expects the best in life — a large well appointed house in the country, foreign holidays in ever more exclusive places, private education for their children. He seems to prosper, but it must be borne in mind that he has also devoured rather a lot of paternal capital.

His third son is perfectly well versed in farming. Indeed he farms. But, having less land than his brothers, he is equally, if not more so, into car rebuilding, trucking and any other kind of enterprise that will make him a quid or two. Consequently, he has an extensive coterie of friends and contacts spanning a wide range of diverse trades. He is a shrewd trader, yet is not averse to freely helping out a friend in need. But for all this he is like a ship without a rudder. He thinks deeply, but never arrives at a firm agenda. Sadly, prosperity rarely seems to come his way.

His youngest daughter is energetic, resourceful and high in confidence. She is also ambitious, dominant and assertive. She works full-time in a company in which she has a sizeable interest. She is fully immersed in the world of modern business and is commercially street-wise. She is prone to sporadic acts of generosity within her extended family, but one is never quite sure whether these are genuine or strategic. Does she do them from the heart, or does she do them to be seen to be doing? It is my judgement that she could be devious if and when it suited her ends. She is rich. Indeed she has by far the most affluent life-style of all the farmer's children.

The farmer's eldest son suffered from many childhood illnesses. But he recovered and attended school. He had to travel quite a distance each day to his secondary school which was about 30 km from his home. He then went on to tertiary education at a farming college. The two other sons were healthy, but proved too much of a handful for their mother. They were therefore sent to boarding school for secondary education where among other things, they learned the more unsavoury arts of life.

I think the middle son must have had some form of tertiary education in farming, but I do know that the youngest son did an apprenticeship in the maintenance and repair of farm vehicles and agricultural machinery. On completion of their tertiary educations, each son went to work on his father's farm as a farm employee paid at the appropriate standard farm worker's wage. However, in addition to his wage, each son also received personal on-the-job tuition in a life-long educational process in which the teacher-to-pupil ratio was a highly effective 1-to-3.

He later divided the farm land between his three sons. At first each son rented the land from him as he had rented fields in his formative years. He slowly-but-steadily handed more and more responsibility over to his sons, each in his own right time, until they were running their portions of the farm themselves. However, he was always available to help and advise them through what was in effect a permanent free-of-charge on-tap professional consultancy service. When he approached retiring age, he gave each of them a 49% share of his respective portion, taking only a nominal rent for the remainder with which to run the farm house and supply his needs in retirement. I think it a fair assumption that he left the other 51% of each portion to each respective son in his will.

The third son's portion of land was not as big as those of the other sons. The farmer considered that his farm was not large enough to support all three of his sons. For this reason he put the youngest son on a farm vehicle and machinery repair and maintenance apprenticeship so that he would have another trade with which to supplement his lesser farming income. He also gave him the free use of a large and substantial farm building to use as a workshop to repair machinery and rebuild cars for profit.

The farmer thus passed on two things to his sons. Firstly he passed on to them his own direct knowledge and experience of the trade he knew. Secondly, he passed on to each of them, in fair measure, the means by which — through the application of the knowledge he had given them — they could freely and independently turn their work into wealth.

As far as his daughters were concerned, I think he supposed that they should be provided for by their husbands who, in turn, he appeared to assume would inherit their means of earning their livings from their fathers.

Apart from the outmoded exclusion of their sisters, the apportionment of his sons' basic inheritances seems equitable and fair. However, due to a combination of defaults and circumstances, our farmer's children have received additional and very disproportionate hidden inheritances.

Having lived all his life in the main farm house which he has now inherited means that the eldest son has also received the equivalent of a free 25-year mortgage on his home. Unlike most people in this country, he never had to endure the crippling capital and interest payments plus all the associated life insurances and other costs. And please be aware that it is not a town terrace or a suburban semi: it is a most desirable 400 year old oak beamed farm house in a private and exclusive country setting.

When his eldest daughter married in 1967, he gave her £260 deposit to buy a small terrace cottage which cost £2600. He guaranteed a bank loan for the remainder which she was to pay off as rapidly as possible. This was achieved after just over two years by taking out a mortgage with a building society. In 1984 (after she and her husband had been struggling to pay their endowment mortgage for 17 years) he gave her a further £10,000. This was towards the £24,600 needed to extend her two-bedroom house to provide another bedroom for her two sons.

It was always understood that his middle daughter would eventually be given the middle cottage in the three-cottage terrace. But this was not to be. As things stand she lives in the farm house but has no part in it. Although she has cared for her father in his old age, she will probably inherit nothing. She will inevitably have to rely on her eldest brother to let her continue to live with him in the farm house when their father dies. But since they do not get along very well, this is open to question.

His middle son lived in the main farm house until he got married in his mid twenties. This son and his wife began married life in one of the end cottages of the terrace which his father gave to them. They took out a mortgage to extend it. He was not as successful at farming as his father. He got into financial trouble. To re-capitalise his farming, he sold his cottage. Being then homeless he pressured his father into letting him move into the detached cottage near the farm house.

His father — our farmer — was still living in the 1940's as far as property prices were concerned and sold it to him for next to nothing. A little later, he got into further financial difficulties and had to sell the second cottage. He used the proceeds to pay off his debts and place a deposit on a well-appointed old forgery house in a village several miles away. So in addition to his basic inheritance in the farm, this son also received an end-terrace cottage plus the difference between the true market price and the nominal price he paid his father for the farm's detached cottage.

Like his middle son, his youngest son also lived in the main farm house until he got married in his mid twenties. However, this son received no cottage. He and his wife started off in a mobile home parked in the farm yard. I do not know who actually paid for it, but I suspect that his father helped him out considerably with its cost. His wife later inherited two houses. With part of the proceeds from these they bought a house in a nearby town. A year or two later, they bought a run-down shack in the country and demolished it. In its place, mostly with his own hands, he built a luxury bungalow. Sadly, they had bitten off more than they could chew. They had to sell it. This caused stress between them and they parted. His wife bought a house in a local village where she lived with their elder son and ran a mobile catering service. He moved back to a spare room in the farm house with their younger son.

His youngest daughter married in 1968. She and her husband rented a bungalow in a nearby town where her husband worked as a mechanic. About 18 months later, they decided they could not afford to live as they were. She also missed the countryside and wanted to move back to the farm. Her father gave her one of the end-cottages of the terrace. So within two years of her marriage at the age of 20, she owned a sound oak-beamed cottage in the country with no mortgage. Unlike most people, they too had no crippling mortgage interest to pay in their formative years. Neither did they have to pay suburban property and water rates. So a few years later they were able to afford to extend the cottage into a substantial house. After that, they extended it further. In 1993 they 'bought' the middle terrace cottage next to theirs from her father which they merged with their existing house. It is now decorated, furnished and fitted to a luxurious standard with outside paved patios and a swimming pool in its 1½ acre country setting.

Through various fortuitous moves, her husband climbed his way up the motor trade. Through his uncle he became a member of a secret society known as the Masons. When a large dealership he was working for was being re-structured to pass down to the next generation, a close friend of his became its new young managing director. He was also a Mason and made her husband his sales director. She also went to work at the dealership. Some years later, so I have been told, when the company was in need of capital, her father gave her £10,000 to buy into it. She and her husband reaped the profits and became very rich. I don't think they have ever gone a year without at least one holiday abroad. Their daughter has been entirely privately educated. They pursue expensive hobbies and travel widely throughout the world.

A summary of how our farmer's wealth and resources have been shared among his children is summarised below.

| Basic Inheritance | Hidden Inheritance | |

|---|---|---|

| Son 1 | 56 hectares of land, farm buildings, personal training, on-going advice. | The Farm House. |

| Daughter 1 | £260 house deposit 1967, £10,000 for house extension 1985. | |

| Daughter 2 | Free lifelong board and lodging in the farm house. | |

| Son 2 | 56 hectares of land, farm buildings, personal training, on-going advice. | An end-terrace country cottage in 1970 + A detached country cottage in 1985. |

| Son 3 | 46 hectares of land, farm buildings, personal training, on-going advice. | Upkeep during apprenticeship, use of farm buildings for motor repair work, mobile home in farm yard. |

| Daughter 3 | £10,000 in 1985 to buy into a motor dealership her husband was working for. | Pitman secretarial course, an end-terrace country cottage 1968, adjoining middle terrace 1993 at far less than market price. A large field adjacent to cottages. |

From this it is obvious that there is a vast disparity between what each of his children has received — even among those of the same sex. I don't think for one moment that our farmer intended such disparity to happen, especially with regard to the hidden inheritances. Nevertheless, the fact of it remains, nowhere more so than between his three daughters.

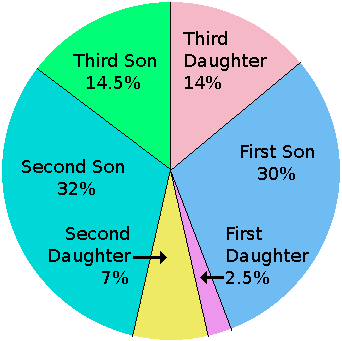

The portion which each of the farmer's children has inherited differs widely. To be able to compare them properly, I have put some kind of financial value on each child's gain. As none of those who received property has had to pay a mortgage on what they have inherited, I have evaluated all their land and property at 1994 prices. I have also valued amounts of money each has received at various times in terms of the equivalent value of the £ in 1994. Resulting relative values of their inheritances (basic plus hidden) are shown in the adjacent pie chart.

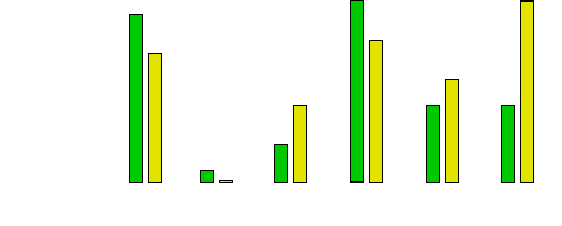

From my extensive knowledge of these people, I have made a subjective judgement as to their relative abilities to 'earn their livings' in 1990's Britain. These values are shown in the 6 right-hand (yellow) bars below. The left-hand (green) bars show the relative sizes of their inheritances as given in the pie chart. As can be seen, the right-hand bars follow a remarkably similar pattern to the left-hand bars.

One factor which contributed to this disparity was undoubtedly nothing more than the way events passively unfolded. For instance, the eldest son and the middle daughter just happened to stay put in the farm house. Therefore she got full board for 30 years and he inherited it. However, apart from the heavy gender bias resulting from our farmer's Victorian thinking, each child's inheritance is simply proportional to his or her degree of assertiveness.

Our farmer obviously planned his sons' basic inheritances. But as far as the hidden inheritances were concerned, he simply responded to pressure. The more ambitious, shrewd, strategic and assertive of his children are the ones he heard the loudest. So to them he gave the most. The less imposing and more considerate of his children — whose needs were in fact the greatest — are the ones to whom he has given the least.

Clearly, when he apportioned the hidden inheritances, our farmer failed to think or plan. He allowed himself to be driven by events. Amazingly, he never seemed aware of the obvious disparity in what he passed on to his children. He always claimed that he had tried to give each of his children the means to do what they wanted. However, I am never quite sure whether he genuinely believed this, or whether he was vainly trying to appease a troubled conscience plagued by the obvious disparity he created.

The greatest disparity is without doubt that between our farmer's eldest and youngest daughters. His eldest daughter has been burdened all her life by mental illness. She has never been able to hold down a job. In fact, for a lot of her life she has needed outside help even to keep house. She has never had a foreign holiday. All throughout our lives together, she and I have had to struggle with a mortgage, town rates and her illness. We now live on welfare and are (consequently) extremely poor. Of all his children, she has always been by far the most needy, yet she has received by far the least.

In contrast, his youngest daughter is the most commercially astute of all his children. She has been able to 'earn' a substantial salary and reap sizeable business and investment profits. She is now extremely rich. She has a luxurious house in the country which she has developed out of the cottage and grounds she was given. She holds a powerful position in a company she partially owns. She drives her own new mid-range Mercedes Benz car. She has always had at least one foreign holiday a year. Lately she has had two foreign holidays a year and many breaks in between in various parts of the United Kingdom — particularly Scotland. She was the least needy, yet she received six times as much as her eldest sister.

So why the disparity between the amounts of the inheritances these two sisters received from their father? It cannot have been based on need. It cannot have been based on merit. It probably resulted from a fusion of their relative levels of assertiveness and ambition, and pure circumstance. In general, therefore, to each of his children, our farmer has apportioned his wealth according to neither need nor merit, but according to pure happenstance carried by the forcefulness with which each of his children was able to 'bend his ear'.

The immediate consequence of the disparity in the amounts and timings of what our farmer has passed on to his children over the space of one generation is that their individual life-styles have differed considerably.

While most have been able to live in country houses, drive posh cars, enjoy foreign holidays, go out hunting on horseback with the hounds, attend social functions and give their children a private education, the eldest sister has had to struggle with mental illness, a mortgage, worry about how to make the food money stretch to the end of the week, and do without holidays, hobbies and entertainment.

But disparity in life-style is probably the least significant consequence of the way our farmer apportioned his wealth. Of far greater impact has been the dichotomy of thought which the disparity of life-style has generated.

When six children have been brought up together on a farm they have a lot in common. They have worked and played in the same woods and fields. They have seen all the cycles of planting and harvest. They have smelled the same summer rain on the ripening crops. They have shared the same winter fireside. They have endured the same lengthy journeys to and from school. They ventured together into the rural community of village fetes and country pubs, bonfire nights and young farmers' clubs. This platform of shared experience enabled them to relate. It supplied a common context through which they could accurately convey thoughts and feelings. It formed the ultimate conduit for human communication.

But when they grew up, their levels of wealth diverged. This gave some of the farmer's children the freedom to do things that the others could not. It allowed them to engage in activities which to the others were out of reach. It caused some to become familiar with objects, activities and places that were outside the others' scopes of experience. For instance, at family events the rich would re-live in conversation the excitement of a holiday in Spain — a place, a climate, a culture, which is meaningless to their poorer siblings. Thus, these people — brothers and sisters who were brought up together and shared the same formative experiences — now live in completely different worlds.

The platform of health, wealth, well-being and life-style from which the farmer's youngest daughter views life and the world is poles apart from the ditch of illness, lack of opportunity, immobility and poverty from which her eldest sister views them. But it is not only their passive views of the world that are different. The way the world actively responds to them is totally different also. One can simply flash a credit card to fulfil a need of even an impulsive whim. The other has to agonise as to whether or not she can afford to allow one of her children to go on an educational school trip. While modern British society sees one as a virtuous success, it regards the other as an unwelcome and undeserving social problem. One is held in respect: the other is eyed with suspicion.

To each sister, the world not only appears quite different, but also exhibits a completely different character and mode of behaviour. Therefore, to each, the world is different.

It is not surprising therefore that whereas they once held similar social, economic and political views, these sisters are now placed at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Not only have they grown apart in wealth, but also in thought. Despite this, they have striven hard to keep a good relationship. But such a relationship has not been sustained between all the farmer's children. Due entirely to the disparity of apportionment, they long ago split into feuding factions.

The disparity of their inheritances gave them a disparity of opportunity for creating their own wealth. This led to a disparity of well-being, life-style and position within society. This in turn resulted in a disparity in the way society regarded and treated them. This created a disparity in their views of society and hence in their social, economic and political philosophies. This in turn led to mutual resentment, argument, open hostility; then rejection and ultimately a complete breakdown in communication.

However, there is a consequence to the way our farmer passed on his wealth that is far more significant than the disparity in the life-styles of his children or the dichotomy of thought this has created among them. This greater consequence is the effect his action has had, and will have, on his future generations. Their greater inheritance has enabled those of his children who received more to produce more and accumulate more. Inherited wealth is, in effect, a means of turning work into more wealth. And the more one receives, the more one can produce.

This means that those of the farmer's children who received more will have even more to pass on to their children or beneficiaries. So if the same rules of apportionment are applied (which they probably will be), the disparity of wealth between our farmer's grandchildren will be even greater than it was between his children. So, as our farmer's wealth and the gain it produces "cascades down the generations", it will naturally and inevitably gravitate more and more into the hands of fewer and fewer.

I must again affirm that all this is how the farmer and his family appear from my point of view as an outsider. I do not — indeed cannot — know every detail of all their business. Nevertheless, I am confident that my observations and data are more than sufficiently accurate to uphold the essence of what I have said.