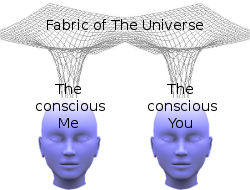

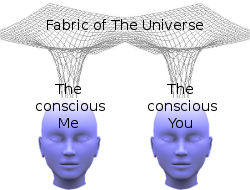

The human is a self-aware conscious entity. But it is not self-existent. It cannot take form within the dark silent prison of eternal isolation. It is a vibrant phenomenon. It can only exist while in a continual state of development. To develop, it must relate with others. For this purpose it has a strong in-built desire to forge relationships. The only means it has of connecting with others is through the physical universe. Its interface with the physical universe is the physical brain within which it finds itself accommodated.

The human is a self-aware conscious entity. But it is not self-existent. It cannot take form within the dark silent prison of eternal isolation. It is a vibrant phenomenon. It can only exist while in a continual state of development. To develop, it must relate with others. For this purpose it has a strong in-built desire to forge relationships. The only means it has of connecting with others is through the physical universe. Its interface with the physical universe is the physical brain within which it finds itself accommodated.

The physical brain is itself accommodated within — and is part of — its physical body. The physical body too is not self-existent. It needs to be sustained by water, food, clothing and shelter from its terrestrial environment. For this purpose, the human is also equipped with a secondary drive. This motivates it to deploy the terrestrial resources around it to generate its economic needs of life.

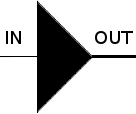

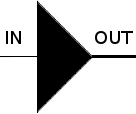

Under normal circumstances this drive is controlled by need. If needs are not met, the drive increases. As needs become fulfilled, the drive diminishes. Consumption thus appears to be regulated by some kind of natural negative feed-back loop. The needs of the body are thus acquired in the correct and balanced measure. The conscious human entity within it is sustained and is therefore free to pursue its primary need: to forge relationships with others and, by so doing, evolve onwards towards its spiritual destiny.

Under normal circumstances this drive is controlled by need. If needs are not met, the drive increases. As needs become fulfilled, the drive diminishes. Consumption thus appears to be regulated by some kind of natural negative feed-back loop. The needs of the body are thus acquired in the correct and balanced measure. The conscious human entity within it is sustained and is therefore free to pursue its primary need: to forge relationships with others and, by so doing, evolve onwards towards its spiritual destiny.

Relating, however, isn't easy. Humans need some kind of framework or context to initiate and stimulate their relating process. Fortunately, such a catalyst appears to be already built into every human population. This catalyst is the clearly observable unevenness in the distribution of human aptitudes throughout any given sample of the human population. It induces people to relate by forcing them to cooperate in the process of providing their common needs of life.

Relating, however, isn't easy. Humans need some kind of framework or context to initiate and stimulate their relating process. Fortunately, such a catalyst appears to be already built into every human population. This catalyst is the clearly observable unevenness in the distribution of human aptitudes throughout any given sample of the human population. It induces people to relate by forcing them to cooperate in the process of providing their common needs of life.

Each individual possesses only a limited set of aptitudes of various strengths. An economic process, on the other hand, requires a much wider set of human aptitudes, all at full strength. To make an economic process work efficiently, it is therefore necessary to form a team of people who together possess a full and balanced set of human aptitudes. To bring all the necessary human aptitudes to bear upon the process, the members of the team must cooperate. To do this they must form working relationships.

Each individual possesses only a limited set of aptitudes of various strengths. An economic process, on the other hand, requires a much wider set of human aptitudes, all at full strength. To make an economic process work efficiently, it is therefore necessary to form a team of people who together possess a full and balanced set of human aptitudes. To bring all the necessary human aptitudes to bear upon the process, the members of the team must cooperate. To do this they must form working relationships.

Working relationships form a catalytic context or framework upon which trust can be built and true friendship can evolve. But something is wrong. Human societies today do not seem to be based on friendship. They seem to be based on self-seeking, competition and adversity.

Always Adequate Resources

To understand why, we must go back a very long time. The population of the Earth is small. There is seemingly unlimited land per head of population. People gather the bounteous fruit of the earth for food. They cut wood for fuel and stone for shelter. They take skins, wool and plant fibres to make clothes. They live well. Mankind begins to multiply upon the Earth. The population density increases at an ever-increasing rate. Ready meals become scarcer. People begin to hunt and farm. When a community needs more terrestrial resources, it simply commandeers more land from the wilderness for farming and hunting.

To understand why, we must go back a very long time. The population of the Earth is small. There is seemingly unlimited land per head of population. People gather the bounteous fruit of the earth for food. They cut wood for fuel and stone for shelter. They take skins, wool and plant fibres to make clothes. They live well. Mankind begins to multiply upon the Earth. The population density increases at an ever-increasing rate. Ready meals become scarcer. People begin to hunt and farm. When a community needs more terrestrial resources, it simply commandeers more land from the wilderness for farming and hunting.

However, there is a limited amount of land on the Earth. Mankind cannot go on commandeering more and more land forever. Nevertheless, it is estimated that this planet has enough resources within its biosphere to support a human population of over 36 billion. Today (2011) there are as yet only 7 billion people on the Earth. That means there are more than 5 times the resources available than is necessary to support the current population.

We have just past the time at which the Earth's population reached its most rapid rate of growth. In the past, we can be certain that it was always very much smaller than it is today. On the planet as a whole, therefore, there can never have been a lack of biospheric resources for the Earth's human population to support itself. There could be shortages in some localities from time to time. But people could always, if free, move to where there was abundance.

We have just past the time at which the Earth's population reached its most rapid rate of growth. In the past, we can be certain that it was always very much smaller than it is today. On the planet as a whole, therefore, there can never have been a lack of biospheric resources for the Earth's human population to support itself. There could be shortages in some localities from time to time. But people could always, if free, move to where there was abundance.

The Ethos of Competition

The upshot of this is that there can never have been a valid reason for people to have to compete for biospherical (i.e. economic) resources. Yet competition seems to be a fundamental characteristic of human society. Nevertheless, however or from wherever it arose, competition certainly did not originate from a vital need to compete for economic resources.

Despite this, a point in history is soon reached at which an individual with the requisite aptitudes and personality traits begins to compete with his fellows in order to gain dominion over them. His form of competition may be plain physical combat. He may shame his fellows into competing with him, knowing that he is gifted with superior abilities in that field. On the other hand, he may do it through words, making his fellows suspicious of each other's intentions and dividing them between themselves. Whatever means of combat he may use, his motive is to gain the subservience of his fellows and thereby acquire greater economic well-being for himself in return for less personal effort.

Having gained domination, he claims by force and fences-off far more land than he can use. Later, when others need that land, he who claimed and fenced it holds onto it by force and charges others rent or tribute for its use. Thus he gets his needs of life by bullying others instead of working. His kind become knights and nobles. Those they vanquish lose their independence and become dispossessed serfs. Thus the many, whose strengths lie in productivity, lose their shares in, and use of, what the Earth provides. Dispossessed of land to independently turn their work into their needs of life, they become cap-in-hand dependent on the exigent few.

Having gained domination, he claims by force and fences-off far more land than he can use. Later, when others need that land, he who claimed and fenced it holds onto it by force and charges others rent or tribute for its use. Thus he gets his needs of life by bullying others instead of working. His kind become knights and nobles. Those they vanquish lose their independence and become dispossessed serfs. Thus the many, whose strengths lie in productivity, lose their shares in, and use of, what the Earth provides. Dispossessed of land to independently turn their work into their needs of life, they become cap-in-hand dependent on the exigent few.

The ethos of competition creates the notion of victory. The victor gains power and control over the vanquished. The vanquished therefore falls into the hands of the victor. In consequence, the vanquished loses all he has to the victor. The victor gains what the vanquished loses. At first, what the vanquished loses and what the victor gains may simply be prestige, as in a modern sport. However, as with sport, the idea of a prize for winning quickly gains acceptance. The victor's prize is inevitably the wealth and possessions of the vanquished.

One driven by the ethos of competition lives by combat rather than by hunting or farming. But his lust for victory is not satisfied when his hunger is assuaged. He does not acquire to fulfil his needs. He acquires for the sake of acquiring. The natural negative feed-back circuit that should regulate his economic process simply isn't there. He isn't satisfied until he has won the world.

One driven by the ethos of competition lives by combat rather than by hunting or farming. But his lust for victory is not satisfied when his hunger is assuaged. He does not acquire to fulfil his needs. He acquires for the sake of acquiring. The natural negative feed-back circuit that should regulate his economic process simply isn't there. He isn't satisfied until he has won the world.

So, true to his nature, the nobleman continues to compete. Having subdued his servile majority, he competes with his fellow nobles. Perhaps in formal competitions of combat. Perhaps through war in which he presses some of his serfs to become soldiers in his private army to fight on his behalf. With time and sophistication, the nobles wage war on each other through complex and deceitful alliances. The strong take over the estates of the weak. The stronger become kings, feeding their extravagant lifestyles from the labour of their subjects. The weak are reduced to serfs and depart to join the swelling ranks of the dispossessed.

So, true to his nature, the nobleman continues to compete. Having subdued his servile majority, he competes with his fellow nobles. Perhaps in formal competitions of combat. Perhaps through war in which he presses some of his serfs to become soldiers in his private army to fight on his behalf. With time and sophistication, the nobles wage war on each other through complex and deceitful alliances. The strong take over the estates of the weak. The stronger become kings, feeding their extravagant lifestyles from the labour of their subjects. The weak are reduced to serfs and depart to join the swelling ranks of the dispossessed.

The Rule of Kings

Though kings rule, they cannot organise and manage everything themselves. There is still a need for middlemen — nobles. Though the king rule, the nobles still own. They have the capital — the resources through which the labour of the many generates the needs of life for all. But the situation is still rather precarious. The king must determine how it will all work.

Though kings rule, they cannot organise and manage everything themselves. There is still a need for middlemen — nobles. Though the king rule, the nobles still own. They have the capital — the resources through which the labour of the many generates the needs of life for all. But the situation is still rather precarious. The king must determine how it will all work.

For this purpose, he creates a system of law. This is a set of rules which, when applied by force to society, facilitate the ordered and peaceful containment and exploitation of the poor by the rich, the weak by the strong, the honest by the devious, the many by the few. This law is enforced by the king's men: a band of official thugs who bully their poor brothers in return for the king's shilling.

For this purpose, he creates a system of law. This is a set of rules which, when applied by force to society, facilitate the ordered and peaceful containment and exploitation of the poor by the rich, the weak by the strong, the honest by the devious, the many by the few. This law is enforced by the king's men: a band of official thugs who bully their poor brothers in return for the king's shilling.

The Noble Thinker

Most kings and nobles concern themselves with rulership, dominion, power, war and wealth. Others, who have already amassed vast estates or empires, become playboys devoting all their time and energies to hunting and merry-making. However, some few become thinkers. They observe nature and study philosophy, science, astronomy. With their needs of life secured, they have the time for free thought and the means to experiment. They record their observations and discoveries, thus bequeathing a wealth of knowledge to future generations.

Most kings and nobles concern themselves with rulership, dominion, power, war and wealth. Others, who have already amassed vast estates or empires, become playboys devoting all their time and energies to hunting and merry-making. However, some few become thinkers. They observe nature and study philosophy, science, astronomy. With their needs of life secured, they have the time for free thought and the means to experiment. They record their observations and discoveries, thus bequeathing a wealth of knowledge to future generations.

The Landed Opportunist

Other nobles later see this bequeathed knowledge as an opportunity to increase their wealth and dominance. They use their capital to finance the development of inventions, based on the knowledge and discoveries of their peers, to establish large scale manufacturing installations within which to mass-produce goods for sale. These noble capitalists then — through various forms of coercion — make it very difficult for common people to survive economically on the land.

Thereby the capitalist forces the common people from their land and villages into cities to work in factories. The villages become all but extinct. The common land of the common people is forcibly enclosed as part of a noble estate. The agrarian serfs become industrial workers. What was once a healthy open rural community becomes a concentrated industrial slum of tiny back-to-back hovels rented from the industrialist. Where once they freely grew their own food, these industrial slaves must now spend their miserable wages buying it from the company store.

Thereby the capitalist forces the common people from their land and villages into cities to work in factories. The villages become all but extinct. The common land of the common people is forcibly enclosed as part of a noble estate. The agrarian serfs become industrial workers. What was once a healthy open rural community becomes a concentrated industrial slum of tiny back-to-back hovels rented from the industrialist. Where once they freely grew their own food, these industrial slaves must now spend their miserable wages buying it from the company store.

Competition in Education

The growth of industry demands a new plethora of specialist skills. A generation or two later, a capitalist-instigated education system is therefore busily disgorging millions of young standardised cogs to power its technology-fuelled profit generators. Being an organ of the State, which is the servant of the capitalist elite, the education system disseminates a curriculum that is inevitably based upon the ethos of competition.

Competition is instilled into the children's minds right from the start. When I was about 10 years old my parents told me that the headmaster of my school, Mr. Potter, had lamented to them that, although my work were excellent, I seemed to lack any motivation to compete and win against my peers in either academic or sporting activities. This was seen as a strange and unfortunate failing.

From then on, I was pressured to compete. It was assumed that if I competed, I would achieve more. The real effect, however, was quite the reverse. I found myself dissipating energy to combat the stress of competing that I could otherwise have applied to my work. As a result, I failed my 11+ examinations and so couldn't go to a good school. Two years later, without any competitive pressure, I passed my 13+ examination and so could then go to a good school.

From then on, I was pressured to compete. It was assumed that if I competed, I would achieve more. The real effect, however, was quite the reverse. I found myself dissipating energy to combat the stress of competing that I could otherwise have applied to my work. As a result, I failed my 11+ examinations and so couldn't go to a good school. Two years later, without any competitive pressure, I passed my 13+ examination and so could then go to a good school.

Later, throughout my working life, whenever I was pressurised to meet deadlines, it slowed me down. When the pressure was off, I worked faster and better. This careful observation reveals the opposite to what the pawns of a capitalist society are taught to believe. They are taught that competing for academic excellence automatically brings the brightest and best to the task of making industry fit to win against foreign competition, and thereby gain the lion's share of global markets.

My natural resolve has always been to devote all my energy to the task-in-hand, without wasting any on the stress of competing against others. My own internal motivation has always been vastly greater than any pressure that others could possibly lay upon me. I later conditioned myself to ignore external pressure. I am not so arrogant as to suppose that I be unique in this regard. I must therefore conclude that there must be a vast multitude of others who share my reluctance to compete.

Notwithstanding, the idealized generic product of the education system is an adversarial confrontational selfish individualist. He seeks wealth and prestige without limit. He has an unquenchable thirst for power and control. He seeks to possess the goods, labour, loyalty and love of others. His relationships are exploitative. He expects to hold exclusive possession: at work, at war, in love. He is the ideal scientist, engineer, professional and bureaucrat of a free-market society.

It always amuses me to see a job advert that asks for a good team player. All the teams I have ever encountered in business, industry and academia seem to be composed of competitive individualists, each of whom, instead of bringing 100% of his energy to bear on the team objective, dissipates most of it unproductively in competition with his team-mates. Bearing in mind the ethos of his formative education, what else could possibly be expected?

The Ubiquitous Merchant

The ethos of competition turns need into greed. It makes people self-seeking to the extreme of relentlessly pursuing unlimited acquisition. So it puts a person with the particular mix of attributes and personality traits that suit him for wheeler-dealing and deception to a great advantage. And alongside the nobles and serfs there has, from early times, existed the wheeler-dealer: the merchant.

He buys, transports and sells what serfs produce upon the lands of their noble masters. Merchants are independent people, buying and selling freely within a market comprising a whole nation of noble estates. In early times, populations are small and spread out. Each merchant consequently finds his own niche in the market. He doesn't need to compete with his fellows. There is plenty of trade for all. He may even cooperate with some of them from time to time in fulfilling a temporary shortage. As populations become larger and denser, the territories and markets of merchants start to overlap. The spirit of competition enters the market.

He buys, transports and sells what serfs produce upon the lands of their noble masters. Merchants are independent people, buying and selling freely within a market comprising a whole nation of noble estates. In early times, populations are small and spread out. Each merchant consequently finds his own niche in the market. He doesn't need to compete with his fellows. There is plenty of trade for all. He may even cooperate with some of them from time to time in fulfilling a temporary shortage. As populations become larger and denser, the territories and markets of merchants start to overlap. The spirit of competition enters the market.

The participants within this competitive environment expend vast amounts of effort competing with each other for market share. Acquiring their needs of life is not the objective. Their objective is simply to gain as much as they can, without limit. Of these participants, only a very small number ever make it big. Nevertheless, some, by fortuitous fluctuations in supply and demand, manage to amass quite a lot of capital. Having done so, some of them decide to look for an escape from their niches of high competition. They seek another area of endeavour within which to apply their accumulated experience and capital.

Thought From The Grass-Roots

Despite having no land, wealth or capital, the well-educated technically-skilled operative possesses a different resource: his brain. That massively-parallel 86 billion neuron supercomputer inside his head starts to apply some lateral thinking to the wealth of knowledge bequeathed by the noble thinkers of the past. He makes scientific discoveries. He visualises technologies. He invents machines. Unfortunately, he lacks the resources to disseminate his discoveries, develop his technologies or realise his inventions.

Though an employee, who is economically dependent on an industrialist for his needs of life, such an inventor also has a sense of independence. He has an independence of mind. He invents an excellent piece of technology from which he conceives a product that almost everybody would like to use. But he has no capital. So he cannot produce it or market it. Typically, his industrialist employer cannot see any value in the inventor's idea and expects him to stop diverting his energy into such stupidity and to get on with his boring work in the office, laboratory or factory. So he decides to leave his employer in order to seek some means of realising his product.

A Bourgeois Alliance

So the ex-merchant (now called an entrepreneur) and the ex-employee (the inventor) get together. They form a joint endeavour to use the entrepreneur's capital and selling skills to realise and market the inventor's product. The product is manufactured. The market devours it. Supply cannot meet demand. Other entrepreneurs set up to produce similar products to fill the slack in the market. For almost all, however, the bonanza is very short-lived.

The situation is by now big enough and obvious enough to attract the attention of the industrialists (the former nobles with their vast wealth and capital). The nobles meet. They decide who shall have this new market sector. Then, the selected industrialist commissions the development of a very similar product to the one the original inventor created. He then uses his vast reserves of capital to produce and market his product on a scale that will completely saturate the market. He thereby puts the original entrepreneur (and all the others that jumped on the bandwagon) out of business and out of capital. The industrialist then goes on to saturate the global market and thereby multiply his wealth and capital.

With every new generation there emerges a new batch of young keen inventors and entrepreneurs who throw their full lives and energies into inventing and launching a new plethora of innovations. Most bloom and die like desert flowers. A few are either bought out or pseudo-cloned by the large corporations of the noble industrialists. Scale and control increase. Potential inventors and entrepreneurs become fearful and wary. Innovation and technology gradually slow down and stagnate into the standardised nirvana of corporate research & development departments. Progress still continues, but only slowly. Technology advances, but monolithically.

Sadly the ex-merchant entrepreneur rarely has the critical mass of capital necessary to win out against the vast wealth of the self-sufficient noble industrialist.

Corporate Dominance

Scale becomes global. Players become bigger and fewer. Once subordinate to the State, they are now becoming global and unaccountable. Competition goes into over-drive. The old competitive ethos becomes overt unmitigated greed.

It is as if the global economic process has acquired a positive feedback mechanism that drives it into a super-regenerative tempest of blind marauding corporate monsters devouring resources and labour; externalising waste, pollution, disease and inconvenience; voraciously concentrating all wealth into the hands of their noble proprietors. This is interrupted with chaotic periodicity by painful recessions (when the global markets saturate and the bankers call in their loans), which is destined to increase in frequency and amplitude until the whole economic process reaches its threshold of destruction.

It is as if the global economic process has acquired a positive feedback mechanism that drives it into a super-regenerative tempest of blind marauding corporate monsters devouring resources and labour; externalising waste, pollution, disease and inconvenience; voraciously concentrating all wealth into the hands of their noble proprietors. This is interrupted with chaotic periodicity by painful recessions (when the global markets saturate and the bankers call in their loans), which is destined to increase in frequency and amplitude until the whole economic process reaches its threshold of destruction.

This unbridled global turmoil forces the demand for specialised skills to polarise geographically. Specialist workers are left with no option but to migrate to alien lands in order to continue in employment. They leave their communities of origin. Ties to extended family become stretched and weakened. Isolated individuals, couples and nuclear families find themselves in endless brick-box housing estates next to neighbours they do not know and with whom they have nothing in common.

Demand for technical and professional workers greatly out-strips supply. Qualified people enjoy high salaries and bountiful life-styles. The education system is tasked to turn out more young graduates qualified for technical and professional jobs. A generation or so later it has produced an over-abundance. The supply for technical and professional operatives now greatly outstrips demand.

Their salaries equalise with those of unskilled workers and even become inferior. Fast-food servers earn more than engineers and scientists. Many professionals find themselves out of work. The Draconian welfare system requires that they take any work at any level. But they are never accepted for lowly jobs. The employer's excuse is that culturally they simply wouldn't fit in with the existing work environment and would lack commitment because they would always be on the look-out for more appropriate employment. They are trapped.

Popular Frustration

When one of these young professionals starts out on his career, he sees good prospects for his future. After all, going by the precedent of past generations when people had life-time job security, this was indeed true. So, in complete confidence, he buys a nice house in a good middle-class housing estate. However, as unbridled free-market capitalism tightens its grip, he soon discovers that he is on the wrong side of the supply-and-demand cycle. There are too many professionals for too few jobs. He is made redundant. Time goes by. He cannot find work, not even a lowly unskilled job. He becomes very short of money. Poverty begins to bite. He can't afford to go out. So he gradually loses contact with his peers.

Meanwhile, next door, a new kind of person has moved in. He is an uneducated unskilled jobber who, during a recent construction boom, happened to fall on his feet and started his own business providing temporary services for large building projects. He has plenty of money. But his social behaviour and life-style are very different from those of his ex-professional neighbour. The nouveau-riche jobber likes to throw parties and play loud music into the early hours. The ex-professional likes peace to read and converse with his family and friends. One annoys the other; the other irritates the one. As neighbours, they are mutually incompatible, like chalk and cheese.

Imprisoned in their suburban isolation, they both become insupportably frustrated. This frustration generates pent up psychological pressure. The powers-that-be are well aware that somehow this pent-up frustration must be contained and released. They have a solution. The competitive drives of these disparate suburbanites must be diverted. It must be focused onto something that can dissipate their frustrations harmlessly through vicarious experience.

Men's frustrations are dissipated through mass spectator sport. In the world as a whole this is mainly football. However, to maintain its attraction, any spectator sport has to provide its spectators with ever-greater intrigue. It must become ever more aggressive. American football is worse. To me, it appears simply as a game of formalised physical violence. In tennis, the ball speed of a serve could soon become lethal. In motor sport, drivers must steer ever more finely along the envelope of instant death. How much further will sport have to go in order to continue to vicariously assuage the frustration of the bored suburbanite? Perhaps, as in Ancient Rome, it will eventually again demand the sacrifice of human life.

Men's frustrations are dissipated through mass spectator sport. In the world as a whole this is mainly football. However, to maintain its attraction, any spectator sport has to provide its spectators with ever-greater intrigue. It must become ever more aggressive. American football is worse. To me, it appears simply as a game of formalised physical violence. In tennis, the ball speed of a serve could soon become lethal. In motor sport, drivers must steer ever more finely along the envelope of instant death. How much further will sport have to go in order to continue to vicariously assuage the frustration of the bored suburbanite? Perhaps, as in Ancient Rome, it will eventually again demand the sacrifice of human life.

Violence seems to be the means perceived by the powers-that-be to quench the frustration of the common people. There are fewer and fewer films with any substance in their content. Some British films still have a measure of literary content but all the American films I see in the cinema and on television seem to contain little other than increasingly more extreme gratuitous violence. That is why I no longer watch television, except occasionally for increasingly flowery and irritatingly presented news and documentaries.

In order to assuage the intellectual and emotional frustrations of women living their mind-numbing roles in office and home, the powers-that-be saturate the television channels with soap operas and the book stands with romantic pulp fiction. Women are expected to be satisfied by living vicariously, day after day, the exotic lives of the participating fictional characters. Again, such material grows ever more violent, the only difference being that in place of physical violence, this brain-fodder for women is filled with ever increasing levels of inter-personal deceit and treachery.

Middle Class Competition

The corporately employed worker is given work to do. The self-employed artisan finds work to do. The unemployed search for a job. But they aren't really competing. None of them has the resources to be able to do so. That's why their natural drives and frustrations must be contained and dissipated as described above.

On the other hand, the middle-class white-collar businessman, executive, scientist, engineer, bureaucrat or professional is definitely in a competitive environment. They were all indoctrinated with the ethos of competition from the very beginning of their education. The businessman competes in the open market. The executive — and to some extent the engineer and the scientist — not only competes in the open market on behalf of his employer, but also against his colleagues to better his position and career. Even bureaucrats and professionals compete against their colleagues for position and prestige.

And competition breeds greed. Bureaucrats, businessmen and executives sit ensconced at the choke-points of financial flow within the economy. Thus having the power to do so, they allocate for themselves salaries that are proportionately more lucrative than they rightly deserve. Consequently, the income gap between them and their workforce grows steadily. Eventually, the lives of the workers become too miserable to tolerate. An economic crisis materialises and the workforce reacts.

I remember a demonstration I once saw of two generators at a power station. They were connected together and spun up for test. They were then switched into anti-phase. The two generators were thus working against each other. They were in competition. Their combined output was small, being only the residual difference resulting from one generator producing a slightly greater output than the other at the time.

I remember a demonstration I once saw of two generators at a power station. They were connected together and spun up for test. They were then switched into anti-phase. The two generators were thus working against each other. They were in competition. Their combined output was small, being only the residual difference resulting from one generator producing a slightly greater output than the other at the time.

Likewise, competition uselessly dissipates the majority of human time and effort, leaving only a minor proportion to fuel production. Human productive effort is thus divided against itself. Competition also causes an economy to gravitate towards a state of ever-increasing disparity in wealth and well-being within its population. As an economic system, a competitive free market is thereby extremely inefficient. That is why, when a nation has its back to the wall in time of war, even the most conservative of governments immediately switch to a command economy.

The Sad Conclusion

There are two fundamental protocols through which a human being may conduct his relationships with his fellows and with the planet on which he lives. These two protocols are mutually incompatible. The first — the protocol of need — directs him to use only his fair share of the planet's resources to turn his labour into his needs of life and to help his fellows in a spirit of friendship. The second — the protocol of greed — directs him to compete with his fellows to subdue and enslave them by taking their rightful shares of the planet's resources for himself in order to gain wealth that is significantly in excess of what he needs or deserves.

Human society comprises billions of individual human beings. Which protocol those individuals follow, in conducting their relationships, determines the complex form and behaviour to which society will tend to gravitate on the grand scale. This complex form and behaviour is, in the terms of complex dynamics, its behavioural attractor. The global effect of everybody following the protocol of need is for human society to naturally gravitate into the form of an intimate egalitarian network. The global effect of everybody following the protocol of greed is what we see today: a society of conflict and disparity, composed of alienated social classes bound under a system of oppressive hierarchies.

These religious, political and economic hierarchies divide, conquer and milk their captive populations. They educate each new generation only in their pernicious doctrine. They make selfishness and competition the mainstream norm. They progressively concentrate wealth and influence until the entire globe is locked in the death-grip of a clique of corporate crooks. On the few occasions when a social idealist gets elected to power, he finds he is not free to implement his policies. On the contrary, he finds himself pushed as if by some kind of incumbent omnipotent juggernaut to conserve the status quo and tread the same old precarious path that meanders like a drunken elephant between boom and catastrophe.

This juggernaut is not the capitalist elite. They are nothing more than a juxtaposed amalgam of self-seeking individualists. They pursue no universal vision of the common good. They do not coordinate or control the global economy, or even a national one. It is as if even this favoured few are mere pawns under the control of a sinister hidden force that is orchestrating the whole repressive process.

This juggernaut is not the capitalist elite. They are nothing more than a juxtaposed amalgam of self-seeking individualists. They pursue no universal vision of the common good. They do not coordinate or control the global economy, or even a national one. It is as if even this favoured few are mere pawns under the control of a sinister hidden force that is orchestrating the whole repressive process.

So, what is this omnipotent juggernaut, this sinister hidden force? It is the mathematical monster that defines the strange attractor to which the large-scale behaviour of society naturally gravitates when people forsake the protocol of need and turn to live by the protocol of greed. Of course, humanity did not, through any conscious consideration, wish this woeful situation upon itself. The whole rancid outcome was immutably foreordained within the fundamental nature of numbers.

Parent Document | © March — November 2011 by Robert John Morton

The human is a self-aware

The human is a self-aware  Under normal circumstances this drive is controlled by need. If needs are not met, the drive increases. As needs become fulfilled, the drive diminishes. Consumption thus appears to be regulated by some kind of natural negative feed-back loop. The needs of the body are thus acquired in the correct and balanced measure. The conscious human entity within it is sustained and is therefore free to pursue its primary need: to forge relationships with others and, by so doing, evolve onwards towards its spiritual destiny.

Under normal circumstances this drive is controlled by need. If needs are not met, the drive increases. As needs become fulfilled, the drive diminishes. Consumption thus appears to be regulated by some kind of natural negative feed-back loop. The needs of the body are thus acquired in the correct and balanced measure. The conscious human entity within it is sustained and is therefore free to pursue its primary need: to forge relationships with others and, by so doing, evolve onwards towards its spiritual destiny.

Relating, however, isn't easy. Humans need some kind of framework or context to initiate and stimulate their relating process. Fortunately, such a catalyst appears to be already built into every human population. This catalyst is the clearly observable

Relating, however, isn't easy. Humans need some kind of framework or context to initiate and stimulate their relating process. Fortunately, such a catalyst appears to be already built into every human population. This catalyst is the clearly observable  Each individual possesses only a limited set of aptitudes of various strengths. An economic process, on the other hand, requires a much wider set of human aptitudes, all at full strength. To make an economic process work efficiently, it is therefore necessary to form a team of people who together possess a full and balanced set of human aptitudes. To bring all the necessary human aptitudes to bear upon the process, the members of the team must cooperate. To do this they must form working relationships.

Each individual possesses only a limited set of aptitudes of various strengths. An economic process, on the other hand, requires a much wider set of human aptitudes, all at full strength. To make an economic process work efficiently, it is therefore necessary to form a team of people who together possess a full and balanced set of human aptitudes. To bring all the necessary human aptitudes to bear upon the process, the members of the team must cooperate. To do this they must form working relationships.

To understand why, we must go back a very long time. The population of the Earth is small. There is seemingly unlimited land per head of population. People gather the bounteous fruit of the earth for food. They cut wood for fuel and stone for shelter. They take skins, wool and plant fibres to make clothes. They live well. Mankind begins to multiply upon the Earth. The population density increases at an ever-increasing rate. Ready meals become scarcer. People begin to hunt and farm. When a community needs more terrestrial resources, it simply commandeers more land from the wilderness for farming and hunting.

To understand why, we must go back a very long time. The population of the Earth is small. There is seemingly unlimited land per head of population. People gather the bounteous fruit of the earth for food. They cut wood for fuel and stone for shelter. They take skins, wool and plant fibres to make clothes. They live well. Mankind begins to multiply upon the Earth. The population density increases at an ever-increasing rate. Ready meals become scarcer. People begin to hunt and farm. When a community needs more terrestrial resources, it simply commandeers more land from the wilderness for farming and hunting.

We have just past the time at which the Earth's population reached its most rapid rate of growth. In the past, we can be certain that it was always very much smaller than it is today. On the planet as a whole, therefore, there can never have been a lack of biospheric resources for the Earth's human population to support itself. There could be shortages in some localities from time to time. But people could always, if free, move to where there was abundance.

We have just past the time at which the Earth's population reached its most rapid rate of growth. In the past, we can be certain that it was always very much smaller than it is today. On the planet as a whole, therefore, there can never have been a lack of biospheric resources for the Earth's human population to support itself. There could be shortages in some localities from time to time. But people could always, if free, move to where there was abundance.  Having gained domination, he claims by force and fences-off far more land than he can use. Later, when others need that land, he who claimed and fenced it holds onto it by force and charges others rent or tribute for its use. Thus he gets his needs of life by bullying others instead of working. His kind become knights and nobles. Those they vanquish lose their independence and become dispossessed serfs. Thus the many, whose strengths lie in productivity, lose their shares in, and use of, what the Earth provides. Dispossessed of land to independently turn their work into their needs of life, they become cap-in-hand dependent on the exigent few.

Having gained domination, he claims by force and fences-off far more land than he can use. Later, when others need that land, he who claimed and fenced it holds onto it by force and charges others rent or tribute for its use. Thus he gets his needs of life by bullying others instead of working. His kind become knights and nobles. Those they vanquish lose their independence and become dispossessed serfs. Thus the many, whose strengths lie in productivity, lose their shares in, and use of, what the Earth provides. Dispossessed of land to independently turn their work into their needs of life, they become cap-in-hand dependent on the exigent few.

One driven by the ethos of competition lives by combat rather than by hunting or farming. But his lust for victory is not satisfied when his hunger is assuaged. He does not acquire to fulfil his needs. He acquires for the sake of acquiring. The natural negative feed-back circuit that should regulate his economic process simply isn't there. He isn't satisfied until he has won the world.

One driven by the ethos of competition lives by combat rather than by hunting or farming. But his lust for victory is not satisfied when his hunger is assuaged. He does not acquire to fulfil his needs. He acquires for the sake of acquiring. The natural negative feed-back circuit that should regulate his economic process simply isn't there. He isn't satisfied until he has won the world.

So, true to his nature, the nobleman continues to compete. Having subdued his servile majority, he competes with his fellow nobles. Perhaps in formal competitions of combat. Perhaps through war in which he presses some of his serfs to become soldiers in his private army to fight on his behalf. With time and sophistication, the nobles wage war on each other through complex and deceitful alliances. The strong take over the estates of the weak. The stronger become kings, feeding their extravagant lifestyles from the labour of their subjects. The weak are reduced to serfs and depart to join the swelling ranks of the dispossessed.

So, true to his nature, the nobleman continues to compete. Having subdued his servile majority, he competes with his fellow nobles. Perhaps in formal competitions of combat. Perhaps through war in which he presses some of his serfs to become soldiers in his private army to fight on his behalf. With time and sophistication, the nobles wage war on each other through complex and deceitful alliances. The strong take over the estates of the weak. The stronger become kings, feeding their extravagant lifestyles from the labour of their subjects. The weak are reduced to serfs and depart to join the swelling ranks of the dispossessed.

Though kings rule, they cannot organise and manage everything themselves. There is still a need for middlemen — nobles. Though the king rule, the nobles still own. They have the capital — the resources through which the labour of the many generates the needs of life for all. But the situation is still rather precarious. The king must determine how it will all work.

Though kings rule, they cannot organise and manage everything themselves. There is still a need for middlemen — nobles. Though the king rule, the nobles still own. They have the capital — the resources through which the labour of the many generates the needs of life for all. But the situation is still rather precarious. The king must determine how it will all work.

For this purpose, he creates a system of law. This is a set of rules which, when applied by force to society, facilitate the ordered and peaceful containment and exploitation of the poor by the rich, the weak by the strong, the honest by the devious, the many by the few. This law is enforced by the king's men: a band of official thugs who bully their poor brothers in return for the king's shilling.

For this purpose, he creates a system of law. This is a set of rules which, when applied by force to society, facilitate the ordered and peaceful containment and exploitation of the poor by the rich, the weak by the strong, the honest by the devious, the many by the few. This law is enforced by the king's men: a band of official thugs who bully their poor brothers in return for the king's shilling.

Most kings and nobles concern themselves with rulership, dominion, power, war and wealth. Others, who have already amassed vast estates or empires, become playboys devoting all their time and energies to hunting and merry-making. However, some few become thinkers. They observe nature and study philosophy, science, astronomy. With their needs of life secured, they have the time for free thought and the means to experiment. They record their observations and discoveries, thus bequeathing a wealth of knowledge to future generations.

Most kings and nobles concern themselves with rulership, dominion, power, war and wealth. Others, who have already amassed vast estates or empires, become playboys devoting all their time and energies to hunting and merry-making. However, some few become thinkers. They observe nature and study philosophy, science, astronomy. With their needs of life secured, they have the time for free thought and the means to experiment. They record their observations and discoveries, thus bequeathing a wealth of knowledge to future generations.

Thereby the capitalist forces the common people from their land and villages into cities to work in factories. The villages become all but extinct. The common land of the common people is forcibly enclosed as part of a noble estate. The agrarian serfs become industrial workers. What was once a healthy open rural community becomes a concentrated industrial slum of tiny back-to-back hovels rented from the industrialist. Where once they freely grew their own food, these industrial slaves must now spend their miserable wages buying it from the company store.

Thereby the capitalist forces the common people from their land and villages into cities to work in factories. The villages become all but extinct. The common land of the common people is forcibly enclosed as part of a noble estate. The agrarian serfs become industrial workers. What was once a healthy open rural community becomes a concentrated industrial slum of tiny back-to-back hovels rented from the industrialist. Where once they freely grew their own food, these industrial slaves must now spend their miserable wages buying it from the company store.

From then on, I was pressured to compete. It was assumed that if I competed, I would achieve more. The real effect, however, was quite the reverse. I found myself dissipating energy to combat the stress of competing that I could otherwise have applied to my work. As a result, I failed my 11+ examinations and so couldn't go to a good school. Two years later, without any competitive pressure, I passed my 13+ examination and so could then go to a good school.

From then on, I was pressured to compete. It was assumed that if I competed, I would achieve more. The real effect, however, was quite the reverse. I found myself dissipating energy to combat the stress of competing that I could otherwise have applied to my work. As a result, I failed my 11+ examinations and so couldn't go to a good school. Two years later, without any competitive pressure, I passed my 13+ examination and so could then go to a good school.

He buys, transports and sells what serfs produce upon the lands of their noble masters. Merchants are independent people, buying and selling freely within a market comprising a whole nation of noble estates. In early times, populations are small and spread out. Each merchant consequently finds his own niche in the market. He doesn't need to compete with his fellows. There is plenty of trade for all. He may even cooperate with some of them from time to time in fulfilling a temporary shortage. As populations become larger and denser, the territories and markets of merchants start to overlap. The spirit of competition enters the market.

He buys, transports and sells what serfs produce upon the lands of their noble masters. Merchants are independent people, buying and selling freely within a market comprising a whole nation of noble estates. In early times, populations are small and spread out. Each merchant consequently finds his own niche in the market. He doesn't need to compete with his fellows. There is plenty of trade for all. He may even cooperate with some of them from time to time in fulfilling a temporary shortage. As populations become larger and denser, the territories and markets of merchants start to overlap. The spirit of competition enters the market.

It is as if the global economic process has acquired a positive feedback mechanism that drives it into a super-regenerative tempest of blind marauding corporate monsters devouring resources and labour; externalising waste, pollution, disease and inconvenience; voraciously concentrating all wealth into the hands of their noble proprietors. This is interrupted with chaotic periodicity by painful recessions (when the global markets saturate and the bankers call in their loans), which is destined to increase in frequency and amplitude until the whole economic process reaches its threshold of destruction.

It is as if the global economic process has acquired a positive feedback mechanism that drives it into a super-regenerative tempest of blind marauding corporate monsters devouring resources and labour; externalising waste, pollution, disease and inconvenience; voraciously concentrating all wealth into the hands of their noble proprietors. This is interrupted with chaotic periodicity by painful recessions (when the global markets saturate and the bankers call in their loans), which is destined to increase in frequency and amplitude until the whole economic process reaches its threshold of destruction.

Men's frustrations are dissipated through mass spectator sport. In the world as a whole this is mainly football. However, to maintain its attraction, any spectator sport has to provide its spectators with ever-greater intrigue. It must become ever more aggressive. American football is worse. To me, it appears simply as a game of formalised physical violence. In tennis, the ball speed of a serve could soon become lethal. In motor sport, drivers must steer ever more finely along the envelope of instant death. How much further will sport have to go in order to continue to vicariously assuage the frustration of the bored suburbanite? Perhaps, as in Ancient Rome, it will eventually again demand the sacrifice of human life.

Men's frustrations are dissipated through mass spectator sport. In the world as a whole this is mainly football. However, to maintain its attraction, any spectator sport has to provide its spectators with ever-greater intrigue. It must become ever more aggressive. American football is worse. To me, it appears simply as a game of formalised physical violence. In tennis, the ball speed of a serve could soon become lethal. In motor sport, drivers must steer ever more finely along the envelope of instant death. How much further will sport have to go in order to continue to vicariously assuage the frustration of the bored suburbanite? Perhaps, as in Ancient Rome, it will eventually again demand the sacrifice of human life.

I remember a demonstration I once saw of two generators at a power station. They were connected together and spun up for test. They were then switched into anti-phase. The two generators were thus working against each other. They were in competition. Their combined output was small, being only the residual difference resulting from one generator producing a slightly greater output than the other at the time.

I remember a demonstration I once saw of two generators at a power station. They were connected together and spun up for test. They were then switched into anti-phase. The two generators were thus working against each other. They were in competition. Their combined output was small, being only the residual difference resulting from one generator producing a slightly greater output than the other at the time.

This juggernaut is not the capitalist elite. They are nothing more than a juxtaposed amalgam of self-seeking individualists. They pursue no universal vision of the common good. They do not coordinate or control the global economy, or even a national one. It is as if even this favoured few are mere pawns under the control of a sinister hidden force that is orchestrating the whole repressive process.

This juggernaut is not the capitalist elite. They are nothing more than a juxtaposed amalgam of self-seeking individualists. They pursue no universal vision of the common good. They do not coordinate or control the global economy, or even a national one. It is as if even this favoured few are mere pawns under the control of a sinister hidden force that is orchestrating the whole repressive process.