I understand certain objects in the outside world. For example, I understand what a car is and what it does.

To do this, my brain has to construct, within itself, a neural model of a car. This model is not a complete simulation of a car. It does not contain all the chemical and thermodynamic equations involved in designing the way the engine efficiently converts fuel into rotational motion. It merely contains a limited simulation of those aspects of a car's structure and functionality that are useful to me. If I really wanted to understand all about a car, the neural model within my brain would have to incorporate every aspect of every nut, bolt and sub-system within it.

I do not understand cars to this depth. However, I did acquire a deep understanding of certain subsystems within aircraft.

Example of Flight-Simulation

I once had the job of simulating, within a digital computer, various types of aircraft navigation equipment and their terrestrial environments. The simulation software that I wrote was to drive full-sized model-specific flight simulators for training civil & military pilots. For this, it was vital that the simulator behave exactly as the real aircraft. Therefore, I had to make sure that my software not only simulated the intended functions of each navigational subsystem, but also its defects and idiosyncrasies.

I once had the job of simulating, within a digital computer, various types of aircraft navigation equipment and their terrestrial environments. The simulation software that I wrote was to drive full-sized model-specific flight simulators for training civil & military pilots. For this, it was vital that the simulator behave exactly as the real aircraft. Therefore, I had to make sure that my software not only simulated the intended functions of each navigational subsystem, but also its defects and idiosyncrasies.

The only way I could guarantee this was to simulate not only what each unit did, but also the way that it did it. This meant simulating every basic component of each unit and the way it interfaced with all the other basic components of the unit. This work made something abundantly clear to me. The software that simulated an aircraft navigation unit was always, by fundamental necessity, more complex than the physical unit it simulated. Add to this the complexity of the hardware of the Honeywell DDP124 computer, on which my software ran, and the complexity became vastly greater than that of the physical unit it simulated.

All that was a long time ago. Today, I am working at my personal computer writing these words. My personal computer is vastly more complex than the Honeywell DDP124 that I used to drive the flight simulators. My personal computer is running the Linux operating system which is, in turn, running many basic services and application programs simultaneously, including the gedit text editor I am using to write these words. A global navigation system far more advanced than the simulator software I wrote in the late 1960s will run in one small corner of my PC while it is doing hundreds of other things at the same time.

The Paradox of Self-Simulation

My personal computer has no problem running a global navigation program, which includes a piece of software that acts as a navigation model of the Earth. But could my personal computer run a complete software simulation of itself?

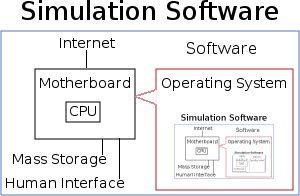

Firstly, my personal computer would have to run software to simulate its own CPU and all the other components on its motherboard, including its 4GiB of memory. It would also have to include simulations of its 250GB disk storage and other peripheral devices. It would also have to include a simulation of the Linux operating system and all the applications and services currently running. It would also have to include a limited simulation of the computer's outside world, including me (its human operator) and the Internet. Only then would it have a means of perceiving its own soul, so to speak.

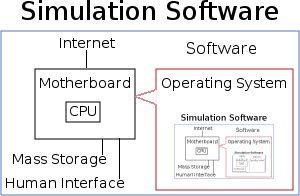

Unfortunately, one of the applications that my computer must run is the software that simulates it. Thus, unavoidably, part of the simulation software must be the simulation software itself, as illustrated on the right. Part of this, in turn, must again be the entire simulation software. The simulation software must therefore contain itself in infinite regression. In other words, the simulation software must be infinitely re-entrant.

Unfortunately, one of the applications that my computer must run is the software that simulates it. Thus, unavoidably, part of the simulation software must be the simulation software itself, as illustrated on the right. Part of this, in turn, must again be the entire simulation software. The simulation software must therefore contain itself in infinite regression. In other words, the simulation software must be infinitely re-entrant.

Each time a program re-enters itself, it has to create a new instance of all its data structures. In the case of my simulation software, the data structures must contain all my computer's 4GiB of memory. Consequently, the second time it enters itself, it will have no physical memory to run in. In fact, it won't have enough memory even to enter the first time through. Thus my personal computer — or any computer for that matter — can never accommodate a simulation of itself.

Partial Self-Simulation

My personal computer cannot accommodate a complete software simulation of itself. But it can accommodate a partial one. My computer is capable of accommodating and running a program that could simulate certain limited-but-relevant aspects of its own functionality.

Likewise, my brain is incapable of accommodating a complete neural simulation of my outside world, itself, my mind and the conscious "me" that is pondering it all. But my brain can accommodate a partial simulation of these things. And this appears to be what it does. It builds, within itself, a neural network that partially models (or simulates) the body (within which it is accommodated) plus its external terrestrial and social environments.

In order to build this internal model, my brain must acquire information from its outside environment. The only way it can do this is via my body's 5 physical senses. These are severely restricted in both type and range. The information they can gather is therefore severely restricted. Furthermore, the human senses can only ever supply a view from one place at a time — from a single point-of-view within space, time and the social order.

An Imperfect Point of View

With my flight simulator software of the 1960s, I was simulating the aircraft's actual navigation equipment. The engineering design information at my disposal gave me a God-like view of the equipment. I could see it, in effect, from all points and from all directions. I could see right inside the very essence of it.

The neural model, within my brain, of my physical and social environments, on the other hand, does not give me this God-like view. I am not privy to the engineering design notes of the physical universe. And I cannot see inside the mind of every other member of society.

Consequently, the neural model of my physical and social worlds is not a true simulation of the physical universe and the society in which I live. It is merely a simulation of my point of view of the physical universe and the society in which I live. Thus the neural model within my brain is not simulating an object but merely a point of view.

This simulation is limited by the inadequate capacity of my brain to hold a complete model of itself, myself and my outside world. It is further limited by the fact that it can receive input only via my physical senses, which are limited in type, range and fidelity. It is limited further still by the fact that my imperfect senses can only view the world from a single point within space, time and the social order. Its ultimate limitation, however, is that, as a purely physical medium, my brain is unable to model or simulate the central hyper-physical component, namely the conscious "me".

These limitations allow my brain to construct only a very crude partial model of reality, which can be seen only from one very narrow point of view. And I suspect that this imposed single narrow view-point makes reality appear much more awkward and complicated than it really is.

© June 2005, Sept-Nov 2014, Jan-Apr 2017 Robert John Morton

Parent Document

I once had

I once had  Unfortunately, one of the applications that my computer must run is the software that simulates it. Thus, unavoidably, part of the simulation software must be the simulation software itself, as illustrated on the right. Part of this, in turn, must again be the entire simulation software. The simulation software must therefore contain itself in infinite regression. In other words, the simulation software must be infinitely re-entrant.

Unfortunately, one of the applications that my computer must run is the software that simulates it. Thus, unavoidably, part of the simulation software must be the simulation software itself, as illustrated on the right. Part of this, in turn, must again be the entire simulation software. The simulation software must therefore contain itself in infinite regression. In other words, the simulation software must be infinitely re-entrant.