One major objective of the landshare concept is that a family farmlet must be able to function in any location within the habitable land surface of this planet. This renders it an absolute requirement that it be totally independent of all external utility services.

Frustrations of Suburbia

The modern suburban home of today simply cannot function without connection to a vast infrastructure of utility services. It has no independent source of water. In many jurisdictions, a householder is prohibited by law from sinking a well and extracting ground water. In many places, he is also required to pay the water authority for any rain water he collects and uses. He is also prohibited by law from processing his own sewage.

The suburban house also has no intrinsic source of energy. Legal restrictions limit most severely the amount of petrol a householder may store. There are restrictions on having diesel generators because of the noise and pollution they produce. In most suburban areas, wind generators are banned because they are deemed to be unsightly. Solar panels cannot be installed without the reluctant planning permission of the local authority. In my apartment, I am forbidden even to install a solar water heater.

From the point of view of so-called green living, the modern suburbanite is pretty well hog-tied. If he wants to go green, he cannot do so unilaterally. He must wait until the local authority or national utility does something about it. But it wasn't always this way. This frustratingly restrictive suburban life is, historically, a very recent phenomenon.

The Times of The Nomad

In ancient times, it is generally assumed, the human species was nomadic. Family groups sheltered in tents of various kinds, lived off the land until the fruit and pastures were exhausted, then moved on to where the grass was greener and the trees bore fresh fruit, leaving the place they had been to recover by natural process. Nature thus provided water, food, clothing & shelter. It also recycled all human waste without harming the environment.

In ancient times, it is generally assumed, the human species was nomadic. Family groups sheltered in tents of various kinds, lived off the land until the fruit and pastures were exhausted, then moved on to where the grass was greener and the trees bore fresh fruit, leaving the place they had been to recover by natural process. Nature thus provided water, food, clothing & shelter. It also recycled all human waste without harming the environment.

Nature was able to cope in these circumstances because the population density was below the threshold within which resident natural processes could provide its needs and absorb its waste without disruption. To live in this way, these people must have had a very wide base of knowledge about nature that penetrated to quite a detailed level. But their reward was a quality and experience of life we cannot have today.

The Advent of Exploitation

Then came civilization, or more correctly, exploitation. After all, looking at it purely from a systems analysis point of view, civilization is essentially the implementation by an elite few of a hierarchical construct known as 'law' whose purpose is to facilitate the ordered and peaceful containment and exploitation of the poor by the rich.

This not only heralded a life of oppression for most in the service of the few, but it also instigated the most inefficient way of applying human labour to terrestrial resources to produce the needs and luxuries of life. The unending quest of that elite few has been therefore to seek any and every possible way of improving that miserably low level of economic efficiency.

The first attempt was the Agricultural Revolution where the elite who 'owned' all the land deployed their slaves (whether bound or waged) in a systematic way to garner their large harvests, which they then sold back to those whose labour produced it. But this was not enough. So along came the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution theoretically could have taken place as early as Roman times. But there was a problem. Industry required a vastly higher concentration of labour than agriculture. Far more people had to live and work within a much smaller area. But cramming people tightly enough to ignite the fire of industry resulted in squalor, pollution and lethal diseases. There was simply too much effluent in too small a space for either man or nature to re-process.

There were two cities in the world that had the means to solve this problem. One was Tokyo and the other was Manchester. They both had something no other cities had. They both had populations that drank tea. Tea proved to be the medicinal astringent that could combat the diseases that thrived in high density squalor. However, Tokyo didn't have the wheel, so the Industrial Revolution started in Manchester.

How my mind remembers those dark Satanic mills of the North Country. The endless grids of two-up-two-down tenements in the dirty cobbled streets in which languished the miserable dispossessed who powered the factories of the rich industrialists. Is it any wonder that it was this very same place which gave birth to socialism and was but a stone's throw from where Karl Marx conceived his original ideas for the Communist Manifesto?

How my mind remembers those dark Satanic mills of the North Country. The endless grids of two-up-two-down tenements in the dirty cobbled streets in which languished the miserable dispossessed who powered the factories of the rich industrialists. Is it any wonder that it was this very same place which gave birth to socialism and was but a stone's throw from where Karl Marx conceived his original ideas for the Communist Manifesto?

Is it also any wonder that it was also the birthplace of petty capitalism, in which those who actually did the work sought vainly to set up enterprises so they could profit from their own labour in a competitive free market? Both valid reactions against elite totalitarian oppression.

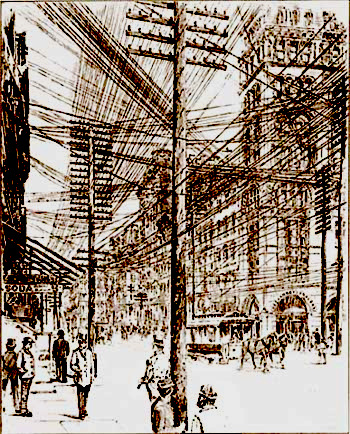

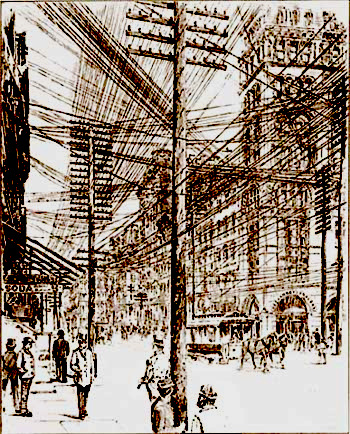

Social pressure forced the development of means to substitute what people had lost by being severed from nature with what were, in the circumstances, seen as better conditions. Part of bringing these so-called better conditions was to give these packed industrial populations the health and convenience of clean water, energy and communication through networked utility services, which were made possible by the technologies developed through industrialisation.

These utility networks soon tangled their way along city streets and even stretched along certain rural routes. But sadly they could never cost-effectively reach the vast majority of the world's habitable land. Civilization was thus constrained to develop only within the close reach of the utility networks, leaving the greater part of our beautiful and resource-rich planet unusable for the benefit of benign human development. The endeavour of civil engineering and planning could therefore only be directed at improving the quality of life within the restricted areas in which existed the high industrial and commercial demand for dense population.

These utility networks soon tangled their way along city streets and even stretched along certain rural routes. But sadly they could never cost-effectively reach the vast majority of the world's habitable land. Civilization was thus constrained to develop only within the close reach of the utility networks, leaving the greater part of our beautiful and resource-rich planet unusable for the benefit of benign human development. The endeavour of civil engineering and planning could therefore only be directed at improving the quality of life within the restricted areas in which existed the high industrial and commercial demand for dense population.

But this brought a spiralling problem. There is a naïve belief among economists, industrialists and social engineers in a universal rule called 'The Economy of Scale'. It purports that the larger the scale on which a process is carried out, the more efficient it becomes and the cheaper is its product. However, practical observation does not support this view.

The Fallacy of Economy of Scale

In 1972 I moved to a small town about 30 km out of central London. It had a population of around 20,000. The local government levied a property tax on our houses called 'rates'. These started off at a reasonable level relative to the average income. Then the town started to expand in order to become a dormitory for people who worked in London and commuted by train every day. Vast housing estates were built. Then more and more. The population more than doubled in 20 years and continued to grow.

You would think — applying the rule of "Economy of Scale" — that the cost of local services per household would decrease. At least, one would think, they should not increase. But they did — astronomically. It seems, therefore, increasing the concentration of housing and extending the area it covers, increases the artificial intervention required to facilitate healthy living. This means increasing population density and extent vastly increases the cost per household for basic utility services. This is because packing humans into a smaller living space makes natural processes less able to supply their needs and dispose of their wastes.

[Here it should be noted that the reason large businesses out-survive small businesses is because their size allows large businesses to dominate markets and prey upon smaller businesses rather than because large business be more efficient.]

Cramming more and more people into the narrow confines accessible to utility networks has many disadvantages both to the people themselves and to the economic infrastructure on which they depend:

It makes them vulnerable to disease, accident or attack. Disease is easily communicated. Any single catastrophe such as fire or flood can hit a large number of people and facilities. A limited military attack such as can be delivered by a small terrorist cell or guerrilla group — whether explosive, chemical, biological or sabotage — can hit a large number of people and facilities.

Also, compared to our nomadic ancestors — or even our agrarian predecessors — our economic imprisonment in suburbia leaves us sorely deprived of the real quality and experience of life which our beautiful planet has to offer.

The immobile nature of the fixed suburban dwelling or city apartment gives rise to a speculative housing market that stifles personal mobility. This, in turn, stifles the whole economic process. It creates a heavy inertia to the whole notion of moving to greener pastures when one's present locality becomes ecologically exhausted and needs to be vacated for a while in order to regenerate naturally.

Below a certain population density, nature can sustainably re-assimilate society's waste and effluent. But when a population grows above a certain threshold concentration, nature cannot dispose of its waste and effluent rapidly enough to keep pace. Artificial means of waste disposal such as land-fill are not only economically expensive, they are also ecologically unsustainable. It's a one-way trip to planetary dysfunction.

Now suppose we take stock of the situation. Our technology has come a long way. We can do things now that we could not do in the heat of the Industrial Revolution. We have a wonderful planet. If we spread out into all its untouched habitable land with our present mentality we will ruin it. But if humanity spreads throughout its planet with a mind to become once again part of the benign natural process, both we and our planet will survive and prosper together.

Universal Terrestrial Dwelling

Key to achieving this is a prototype dwelling in which it is possible to live in sustainable harmony with nature anywhere on the habitable surface of the planet — independently of utility services or even roads.

It is a home designed specifically to impinge as little as possible upon the terrestrial environment, while at the same time being luxurious and comfortable. It has its own deep probe for detecting water, complete with built-in testing and purifying capability. It has its own mechanism for processing and re-cycling waste. It has its own means of abstracting all the energy it needs from the sun and the wind. It has its own high-technology facilities for growing food within its immediate hinterland.

It is semi-vehicular or, at least, transportable so it can move on to a new place when circumstances demand. Naturally it can be as various in shape and décor as the individuals who inhabit it. However, a sensible system of technical standardisation ensures that variety is achieved efficiently and cheaply.

This is the means by which mankind will become able to spread out once again to regain his lost inheritance, namely, the beautiful Planet Earth. Think what advantages this brings:

A distributed or dispersed target is difficult to attack. A nation of distributed self-sufficient homes is far less vulnerable to both military and terrorist attack. Survivors of any destroyed homes can double up with others until their homes can be replaced.

A distributed population can live in harmony with nature because its density is below the threshold at which nature can dispose of waste and effluent sustainably without collective intervention.

With real space, fresh air and inspirational scenery, a quality and experience of life is available to all that nurtures the human spirit and equips it properly for its long-term destiny.

I have designed a research prototype version of a utility independent universal terrestrial dwelling for the Landshare Project. It is comfortable and luxurious. This may sound extravagant, but it isn't. Eco-friendly does not mean austerity.

A guiding policy of the design is that it have minimum impact on the land. The dwelling is therefore designed to be semi-vehicular. Were it to be moved to research other climates and environments, the natural forest would reclaim its land, leaving minimal evidence that the dwelling was ever there. The design is thus, in a sense, a luxury hi-tech version of the tepee used by the ancient nomads that once roamed freely across the planet.

The dwelling is made up of functional modules, each of which is designed to be host to a particular kind of domestic, economic or intellectual activity. The design process applies the science of activity analysis to see in what way, and how strongly or weakly, these different activities interact. The modules are then connected together according to an arrangement that minimises the human effort needed to live and work in the complete dwelling.

NEXT PREV ©June 2003, October 2012 Robert John Morton

In ancient times, it is generally assumed, the human species was nomadic. Family groups sheltered in tents of various kinds, lived off the land until the fruit and pastures were exhausted, then moved on to where the grass was greener and the trees bore fresh fruit, leaving the place they had been to recover by natural process. Nature thus provided water, food, clothing & shelter. It also recycled all human waste without harming the environment.

In ancient times, it is generally assumed, the human species was nomadic. Family groups sheltered in tents of various kinds, lived off the land until the fruit and pastures were exhausted, then moved on to where the grass was greener and the trees bore fresh fruit, leaving the place they had been to recover by natural process. Nature thus provided water, food, clothing & shelter. It also recycled all human waste without harming the environment.

How my mind remembers those dark Satanic mills of the North Country. The endless grids of two-up-two-down tenements in the dirty cobbled streets in which languished the miserable dispossessed who powered the factories of the rich industrialists. Is it any wonder that it was this very same place which gave birth to socialism and was but a stone's throw from where Karl Marx conceived his original ideas for the Communist Manifesto?

How my mind remembers those dark Satanic mills of the North Country. The endless grids of two-up-two-down tenements in the dirty cobbled streets in which languished the miserable dispossessed who powered the factories of the rich industrialists. Is it any wonder that it was this very same place which gave birth to socialism and was but a stone's throw from where Karl Marx conceived his original ideas for the Communist Manifesto?

These utility networks soon tangled their way along city streets and even stretched along certain rural routes. But sadly they could never cost-effectively reach the vast majority of the world's habitable land. Civilization was thus constrained to develop only within the close reach of the utility networks, leaving the greater part of our beautiful and resource-rich planet unusable for the benefit of benign human development. The endeavour of civil engineering and planning could therefore only be directed at improving the quality of life within the restricted areas in which existed the high industrial and commercial demand for dense population.

These utility networks soon tangled their way along city streets and even stretched along certain rural routes. But sadly they could never cost-effectively reach the vast majority of the world's habitable land. Civilization was thus constrained to develop only within the close reach of the utility networks, leaving the greater part of our beautiful and resource-rich planet unusable for the benefit of benign human development. The endeavour of civil engineering and planning could therefore only be directed at improving the quality of life within the restricted areas in which existed the high industrial and commercial demand for dense population.