The economic world is made up of many national economies. Different countries have different types and quantities of natural resources. They also have available different types, quantities and levels of human skill. This creates two disparities.

-

Firstly:

It creates international disparity in the quality of life afforded to individuals with identical types and levels of skill and levels of productivity.

A North European labourer enjoys a much higher standard of living for his labour than does a labourer in the Third World.

-

Secondly:

It creates disparity in the exchange value of identical goods or services depending on where those goods are bought and where they are sold.

A kilogram of lentils grown in Somalia and sold in the USA costs far less to the purchaser as a proportion of his total income than does an identical kilogram of lentils grown in the USA and bought in Somalia. Yet lentils are lentils. Wherever they are grown and wherever they are sold, they still provide exactly the same proportion of the protein and energy needs of the human body. They have the same intrinsic value.

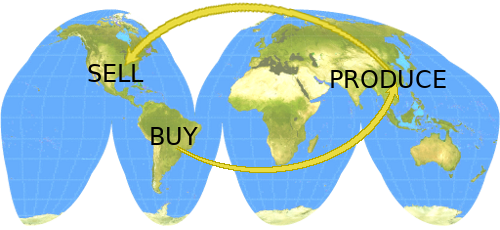

The Connected Capitalist

The capitalist has the means to set up business, hire labour, buy his raw materials and sell his goods anywhere in the world. He may buy in one country, produce in another and sell in a third. The world is his market.

Capitalist enterprises are globally connected. They are able to transcend international boundaries with little effort or inconvenience. They can buy from where they will. They can sell where they will. They can employ locally at subsistence wages and sell globally at high prices. Collectively therefore, they do not rely on what they pay their local employees to provide the revenue to buy their goods and services from which their profits are derived. They can produce in (or buy from) a poor country and sell in a rich country. They do not therefore depend on the spending powers of consumers local to themselves to provide the revenue necessary to sustain high profits.

They also have the financial power to influence the consumer mind through the world's mass-media. They hereby change at will the fads and fashions of the market, and hence manipulate demand to suit their ambitions.

The Isolated Consumer

The dispossessed individual, on the other hand, is economically trapped within his immediate locality. This is true in both his economic roles, namely:

- as a wage earning labourer, and

- as a consumer of goods and services

As a labourer, he does not have sufficient means to switch his employment arbitrarily between different parts of the world. Relocation is to him an expensive and traumatic undertaking. It cannot be done often. He is economically constrained to work locally.

Furthermore, the division of labour has made him too specialised for there to be many employers within reach of his home with need for his skills. If he were to withdraw his labour from his employer unilaterally, his employer would soon find a local replacement. If he and his peers were to do it collectively, their employer would switch production to another country where there is no dispute. If his skills should become available more cheaply in another country, his employer will undoubtedly switch to that other country anyway. He and his peers would then be redundant, lose their jobs and become poor.

As a consumer, he has insufficient means to enable him to buy and transport his needs of life from anywhere in the world. This constrains him to buy his needs locally from the very small number of capitalist enterprises within reach of his home. If he currently has a job and a car, this may be as much as 50km. If he is unemployed it may be no further than walking distance. Being thus geographically restricted, the consumer has no choice but to buy from the local capitalists whatever goods they choose to make available to him, and at whatever price they ask.

If he loses his job, the consumer will be no longer able to buy as much goods as before from the capitalist producer who once employed him. To the capitalist, however, this is no more than a small short-term inconvenience. He has the means quickly to switch the sales of his goods to other hungrier markets on the other side of the world. Thus is the consumer market always a seller's market through which the connected capitalist is able to dictate his terms of trade to the isolated consumer.

Diminishing Quality of Life

In the past, the labouring consumer was, at least, closely connected to his peers through his local community. But the conditions created by modern housing developments have now left him totally isolated in his home. As such, he relies totally on a cartel of local capitalist enterprises for all his needs of life. He has to choose from what they decide is profitable for them to make available to him at the prices they choose. They are in control. They therefore extract from him as much of his income as they can in return for as little as necessary to sustain his physical needs and allow him to function acceptably within the society in which he lives.

They immerse and imprison him in an economic environment, which they maintain in a constant state of turmoil. This subjects him to the stress of being forced to buy goods which are expensively wrapped, badly made, short-lived, irreparable, of narrow choice, and which are quickly and deliberately driven into obsolescence by forced changes in design, technology and fashion. This, in turn, creates unprecedented and unnecessary waste, which stifles the processes of nature.

Parent Document |

©September 1995 Robert John Morton