Ch11: Footnotes

Freedom Illusion

Democracy

Exploitation

Profit and Tax

Citizen or Subject

Public Ownership

Personal Worth

Authority

Human Society

Omnipotent Cretins

Parable of Cows

My Disclaimer

Imaginary Friend

My Ancestry

Politics

Ownership of all economic resources by a favoured few enables them to exploit the dispossessed many. Socialists therefore deemed that they be owned by all. This inevitably translates into ownership by a single despot, which proves to be worse than ownership by a favoured few.

Under capitalism, the vast majority of mankind own none of the planet's natural means of production. Neither do they possess or control any of the artificial means of production, distribution or exchange, which are created and are sustained by their own hard labour. All such things are owned and controlled by an elite minority known as capitalists.

Under capitalism, the vast majority of mankind own none of the planet's natural means of production. Neither do they possess or control any of the artificial means of production, distribution or exchange, which are created and are sustained by their own hard labour. All such things are owned and controlled by an elite minority known as capitalists.

Under capitalism, the labourer receives, in return for his labour, a wage which always gravitates towards the minimum necessary to sustain him at a level just sufficient for him to function within the society in which he lives. However, the capitalist, for whom he works, takes for himself as much profit as he can from the revenue he gets by selling the fruits of the labourer's work. From this profit, the capitalist then buys his own needs and luxuries of life. What remains is added to his existing capital, thus enabling him to command the labour of even more dispossessed labourers.

In a capitalist society, wage-labour provides no capital for the labourer. Capital created by labour becomes the private property of the capitalist. The capitalist's private capital is therefore the result of his exploitation — his short-changing — of the wage-labourer.

In recent times, in certain countries, thinking people have — through great tribulation — sought to establish an alternative kind of socio-economic system, based on different rules of acquisition and ownership. This alternative system is known as Socialism, although the meaning of the term itself, in today's capitalist world, has become severely diluted. Socialists argue that, since capital be created only by the collective effort of most — if not all — members of society, capital is necessarily a collective product. They therefore deem it to be collectively owned by those who produce it — namely the whole of society. So capital — the profit gained from any joint economic enterprise — is declared to be public property.

In recent times, in certain countries, thinking people have — through great tribulation — sought to establish an alternative kind of socio-economic system, based on different rules of acquisition and ownership. This alternative system is known as Socialism, although the meaning of the term itself, in today's capitalist world, has become severely diluted. Socialists argue that, since capital be created only by the collective effort of most — if not all — members of society, capital is necessarily a collective product. They therefore deem it to be collectively owned by those who produce it — namely the whole of society. So capital — the profit gained from any joint economic enterprise — is declared to be public property.

By deeming all capital to be public property, socialists do not thereby seek to make personal property public. Under socialism, the individual still has the right to acquire property as the fruit of his own labour. His clothes, his furniture, his home, and the tools of his trade, all remain his private property. Thus, only that property which is intrinsically social in nature — which is produced collectively — is deemed to be public.

Private capital is the essence of a system for creating and accumulating wealth that is based on the principle of the exploitation of the many by the few. Capital is that form of property which is acquired by taking to oneself — siphoning off — a proportion of what is produced by the labour of others. Capital consequently becomes that form of property which enables one to command the labour of others, and by so doing increase the amount of capital one possesses.

In a capitalist country, the fruit of the labour of the many — being owned by the few — is used simply to increase further the accumulated capital of the few. Socialism denies the individual the right to accumulate capital. So, in a socialist country, the capital generated by the labour of the many — being owned collectively by all — becomes available to widen, enrich and enhance the lives and well-being of all.

To transform a capitalist country into a socialist country, all private means of production, distribution and exchange must be confiscated and placed under the collective ownership of the entire population. This includes both natural resources and artificial infrastructure: land, capital, credit, shops, factories, schools, transport and communications. Private inheritance is abolished. All jointly inherit everything. Everyone has an equal obligation to work, the wages for which are subjected to a heavy progressive income tax. Free compulsory full-time education is provided for all children.

Originally, socialism also resolved to redistribute people back from the cities to the countryside. There they could regain the quality of life presumed to have been enjoyed by people before they were forced, by economic circumstances, into the swelling cities to power the factories of capitalism. Under socialism, therefore, the dispossessed labourer, for the first time in history, has a share in the ownership of the productive resources of the land within which he lives. For the first time since the enslavement of the ancient settler, he actually belongs. He has a home.

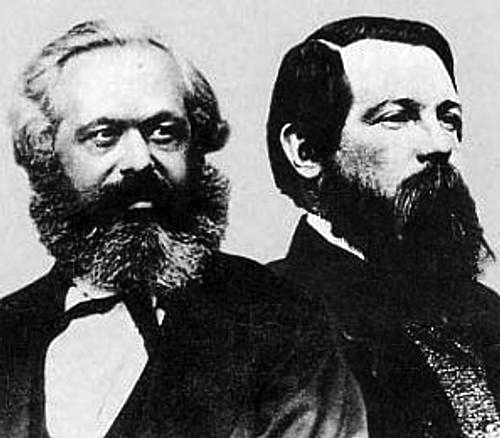

The fathers of socialism were noble people. Their heart was in the right place. Unlike capitalists, who unashamedly condone the pursuit of naked self-interest by ruthlessly exploiting their fellow beings, socialists care about others. Their desire is to see the common inheritance of Planet Earth, plus the labours of those who can labour, applied to the benefit and well-being of all.

The fathers of socialism were noble people. Their heart was in the right place. Unlike capitalists, who unashamedly condone the pursuit of naked self-interest by ruthlessly exploiting their fellow beings, socialists care about others. Their desire is to see the common inheritance of Planet Earth, plus the labours of those who can labour, applied to the benefit and well-being of all.

I applaud them. When I hear their infamous Battle Hymn — be it by the inimitable Red Army Choir or by a devout socialist folk singer — I am stirred. When I read its words — whether the original by Eugene Pottier or a more modern version such as Billy Bragg's — I marvel at its incisive truth. It makes the call to a far deeper and more fundamental allegiance than that to any king or country. It calls for one's allegiance to humanity itself.

But socialism has so far failed. This is generally because it has been undermined and destroyed by the covert actions of capitalist States, or has become so diluted with the means and methods of capitalism as to be barely recognisable. There is, however, a further and more fundamental reason for its failure.

The problem with socialism is its notion of ownership. The land within a socialist country, being collectively owned, is one single object. So is the labour force. So is the infrastructure — the means of production, distribution and exchange. To each of these objects is applied a method to cause it to perform one of the functions necessary to generate the needs of life. However, any one function performed by applying a method to its object cannot alone deliver any of the needs of life to any individual. All essential functions of the socialist economy necessarily contribute to the delivery of the needs of life to each individual. A socialist economy is therefore a single machine in which all land, labour and infrastructure are mere components, each of which alone can provide nothing.

A machine, in order to perform its function properly at all times, has to be controlled. And this control must come from a single source. The limbs of a man with 50 million heads could not be made to move with sufficient coherence to expedite a single simple constructive task. One body must be controlled by one brain ruled over by one will. Likewise, an integrated economic machine must be controlled by a single control system which in turn expedites the singular coherent will of one mind. And being necessarily singular, it must, in consequence, be centralised.

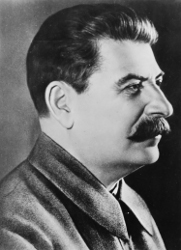

In a socialist State, therefore, control of all resources inevitably gravitates to a single central committee. And as we all know, control of any committee invariably ends up in the hands of its most dominant member. Consequently, as is observed, the socialist State is inexorably bound to fall under the exclusive control of one single dominant personality. Control is possession. Control is centralised, therefore so is possession. Rationally, the socialist State is owned by its leader. Of course, his possession can only be for as long as he is leader. Nevertheless, being in possession of such a great thing as a nation grants its possessor immense power. This is why the leaders of socialist States are so notoriously difficult to dislodge.

In a socialist State, therefore, control of all resources inevitably gravitates to a single central committee. And as we all know, control of any committee invariably ends up in the hands of its most dominant member. Consequently, as is observed, the socialist State is inexorably bound to fall under the exclusive control of one single dominant personality. Control is possession. Control is centralised, therefore so is possession. Rationally, the socialist State is owned by its leader. Of course, his possession can only be for as long as he is leader. Nevertheless, being in possession of such a great thing as a nation grants its possessor immense power. This is why the leaders of socialist States are so notoriously difficult to dislodge.

A settler, who possesses his landshare, has total personal control over its use as the means of turning his labour into his needs of life. The citizen of a socialist State has collective possession of his entire country, but he has no personal control over any of it. That is centralised in the hands of its leader. Since he has no control over any of it, he in fact possesses none of it.

Collective ownership is therefore non-ownership. An individual citizen of a socialist State no more controls the means of turning his labour into his needs of life than does the employee of a capitalist's limited liability company. Instead of the profits of labour ending in the pockets of a few petty capitalists, all the profits of labour fall under the control of a Head of State. Being under his control, he decides how, and on what they are spent. Natural self-interest guides him to satisfy first his own needs and luxuries of life, then those of his family, friends and colleagues. All that remains — which hopefully is almost all — is then naturally spent on what that Head of State perceives to be the needs and priorities of his nation.

But a Head of State is only human. No matter how many advisers beset him, he still has only one single 86 billion neuron human brain with which to orchestrate the affairs of all the other millions of human beings which make up his vast nation. The nervous system by which his single human brain is connected to the limbs of the nation is a lumbering bureaucracy whose information speed and bandwidth is far too narrow to adequately convey the reality of the needs and priorities of its common people. It is like the dinosaur whose tail a predator could devour before its nervous system would relay the pain of the predator's first bite to its tiny brain so far away. The governing elite of the socialist State can thus be every bit as unaware of — and unresponsive to — the conditions of life of the common people as can an aristocracy or a capitalist free market.

To resolve an issue, therefore, the grass-roots individual, finds himself having to reason convincingly and successfully with what appears to be the most enormous, insensitive, omnipotent cretin. The upshot is that a citizen of a socialist State, like the subject of a capitalist State, does not control the State: the State controls him. He does not order his own mode of life. His destiny too is determined by an elite — a socialist elite.