Suppliers of products or services are prohibited from, among other abusive practices:

I - making the supply of a product or service conditional on the supply of another product or service, as well as, without just cause, on quantitative limits;

But this was the cheapest service TIM would offer me. TIM would only provide the basic service bundled with all these extras, which I didn't want and for which I had absolutely no use. In my view, it is a form of pilfering, or perhaps more correctly, a form of taxation. It makes TIM, in effect, a private sovereign state with the power to impose a purchase tax, on top of which the political State and Federation impose their own taxes.

Another equally valid view is that I, as an old-age pensioner, am forced to subsidise services that the young to forty-somethings' double-income families, with their microscopic eyesight, are able to use and benefit from. A clear case of the capitalist principle that 'the poor should subsidise the rich'.

There may be an attempt to 'legalise' the sale by providing intentionally obscured convoluted procedures within the TIM app whereby customers may later opt out of these extra separately priced facilities. But I haven't managed to discover how to do this, if indeed it be possible.

This all reminds me of the so-called 'Windows Tax' imposed by a sovereign state called Microsoft on all personal computers purchased throughout the world. I remember feeling cheated whenever I bought a new personal computer as I was wiping Microsoft Windows from the hard drive to install Linux. I understand that there was some complicated procedure for getting reimbursed. However, this was so difficult to expedite that I never managed to do it. Besides, I have the distinct impression that the amount reimbursed was suspiciously small.

My sign-up to the service was conducted via the salesperson's small tablet device. She demonstrated the various plans of which the one I bought was the cheapest on offer. Of course, I have no idea of the content of the plan except by what she told me verbally, as the print on the tablet screen was too small and complicated for me to read. I never had sight or sound of any terms & conditions, or of the contract itself before signing.

As with all such transactions between an individual and a large corporation, the sign-up was conducted in a manner of 'soft railroading' during which there was obviously no intention that the customer should actually read the fine detail of what was provided in the plan, the contract or the terms and conditions governing it. There was no point. The plan is governed by a Standard Form Contract, meaning that the contract and terms are a fait accompli, which the customer has no power to question or alter. Ipso facto it is an ultimatum: not a contract. As if with the Sword of Damocles poised above his head, the victim has to make Hobson's choice:

"sign-up or be deprived of what is now the de facto [the only practicable] means of your being able to fulfil your legal obligations and exercise your civil rights within the sovereign jurisdiction in which you live".

So I do not know — and it is now irrelevant for me to even investigate — whether or not, somewhere within the terms of the contract, there exists phraseology affirming that I have freely accepted the bundled plan. Legally, I may have done so: factually I did not — and cannot have — done so.

An Unfair Contract

There is a significant imbalance in financial and legal strength between the two parties [a multinational corporation versus an individual citizen] to the so-called 'contract'. The enforced inclusion of additional unwanted services is not necessary to protect the interests of the dominant party [except insofar as its absence would deny the stronger party the extra profit gained if left free to pilfer the cost of the unwanted extra services from the weaker party], while it does financially harm the weaker party in his having to pay for extra unwanted, unnecessary and sometimes dysfunctional services — especially if he is one of Brazil's 59 million poor or 9·5 million extremely poor, who are all supposedly expected to possess workable means for fulfilling their legal obligations and exercising their civil rights.

Significant imbalance, lack of necessity and harm to the other party are characteristics of what the UK's Unfair Contract Terms Act considers to be an unfair contract. I know that Australia has something similar. I don't know about Brazil or elsewhere. However, under such legislation, any clause that is judicially deemed to be unfair is automatically null and void.

I consider the TIM bundle contract, with which I am now lumbered, to be clearly an unfair contract. Having looked at mobile telephone service offerings in the UK, I see that basic 'phone+SMS+internet' options are readily available in the UK for accessible prices. Bundling may occur but the clear and well visible existence of the simple unbundled services strongly suggests to me that, under UK law, offering only bundled services would be illegal under the Unfair Contract Terms Act, which, as far as I know, has no counterpart in Brazil.

One of the pieces of advice given regarding unfair contracts is that "if you haven't yet signed the contract but perceive it to be unfair, walk away". But this immediately precipitates the question: "Can I walk away from the only practicable means of fulfilling my legal obligations of citizenship and exercising my civil rights?". Well, of course, I could simply go to another provider.

But other providers are also big corporations that operate in the very same market. They may or may not confer with each other either as an open industry association or a closed corporate clique, in drafting a Standard Form Contract for the telecoms industry. Either way, the established methodologies of business optimisation lead naturally to an almost identical set of offerings governed by what, under the same universal system of law, evolve into almost identical standard form contracts. Thus, by default, whether actively or passively, the large ISP corporations operate as what is, in effect, a standard form contract cartel. So the hapless victim is trapped into what is essentially the same deal.

In the context of a de facto vital service, whereas the individual consumer is free to walk away from the offerings from any individual corporate provider, he isn't free to walk away from the entire market — i.e. the collective, comprising all such corporate providers. He definitively isn't free to be unable to fulfil his legal obligations or exercise his civil rights. Consequently, the individual consumer has no choice but to sign at least one such contract with at least one such corporate provider. It thus follows that whichever such contract he signs, he necessarily — by default — signs it under duress.

As the victim of the Big Bad Pedro said:

"Señor, I had a-no choice.

He was a-holding ze pistola".

Right of Citizenship

There are millions of people in Brazil who are exceedingly poor. On the other hand, the dominant elements of modern society have engineered it such that for the individual now to be able to meet by any practicable means his minimum necessary and sufficient civil obligations and exercise his basic rights, he must have an Internet connection. The old ways have been deliberately side-lined or discontinued. Government and commerce have 'burned the old bridges', thus rendering the possession, connection and the ability to use a smartphone to be now an unavoidable necessity.

Internet Bill of Rights Chapter II: Users' Rights and Guarantees:

Art. 7º Internet access is essential to the exercise of citizenship, ...

Consequently, it must be incumbent upon society to make bona fide Internet access either free or comfortably affordable by the poorest. And because the smartphone is being relentlessly forced into the position of being the de facto — and indeed sometimes the exclusive — means of access to a vital service, the term 'Internet' service must necessarily include 'mobile telephone' service.

So, I have to ask: how are the millions of very poor expected to be able to pay for something which is necessary to their exercise of citizenship when they have to pay additional costs for lots of services they don't need, don't want and can't use? Are they expected to endure dire hardship to pay for such unwanted extras? Or are they simply, by this means, to be inductively denied citizenship in order to survive?

Be not deceived. This will not stop. The sole objective of a corporation is to maximise profit by exploiting its market of hapless individuals by bundling as much as they can with the provision of a basic service that the citizen can neither practically or legally do without. So don't be surprised if the next telephone/internet plan you buy cannot be bought other than bundled in with a whole host of expensive and unwanted cooking, cleaning, back-scratching and ass-wiping services.

So it would seem that large corporations — especially telecoms — are big enough to be above the law and to violate it with impunity. I need to resign myself to the fact that it 'goes with the territory'.

When I signed up for the above plan with TIM, I had no choice but that at least the first monthly bill be paid by direct debit [Pago Automático]. TIM demanded my bank details, which I gave. TIM told me that I could use the app to change to payment on receipt of the monthly bill once the first payment had been made by direct debit. The first payment was to be debited from my account by TIM on 07 May 2025. The TIM app confirmed that I was on Direct Debit. Notwithstanding, on 08 May 2025, the app also prompted me to pay via a manual transfer method of my choosing. I was confused.

Naturally I did not pay by manual transfer because the app stated that Direct Debit was active. I received lots of SMS messages and some phone calls supposedly from TIM asking me to pay and when I would do so. There are such a lot of scams whereby cyber criminals send such demands falsely, so since I was on Automatic Debit, I assumed these demands were scams and duly ignored them.

Then I discovered via my banking app that nothing had been deducted on 05 May as scheduled. I waited a week and checked again. The Direct Debit had still not been taken. Of course, neither TIM nor the bank intimated anything about an attempted direct debit having been made or rejected. I had to deduce for myself that TIM had submitted the Automatic Debit demand and that the bank [Caixa Economica Federal] had refuse to accept it. So I eventually had to assume blind that the bank had refused to pay the Automatic Debit.

Since I came to Brazil in 2004, my wife had always insisted that, because I had spent my money buying our apartment in 2005, she would pay all our ongoing costs of living. However, when she became unable to take care of such things as her Alzheimer advanced, I acquired provisional power of attorney for her through a Provisional Judicial Instrument of 24 July 2023 whereby I became responsible for handling my wife's affairs, including finances. Notwithstanding, although I explained this to the bank and gave the bank a copy of the Provisional Judicial Instrument, the bank refused to grant me official access to my wife's account before the Definitive Judicial Instrument had been issued. Now, in May 2025, I am still waiting for this Definitive Judicial Instrument to be issued. My lawyer said the bank was obliged to give me control under the Provisional Instrument, but because it has refused to do so, the Judge will have to issue a direct instruction to the bank, which will take time to expedite. I think this is the most likely reason why the Direct Debit was declined.

I did not know how to use the banking app to make a payment nor had I received any information from TIM on how to make the payment. I had received no bill. Then a young relative told me that I was supposed to download the bill via the TIM app. Apparently this first monthly bill for the TIM service had arrived within my TIM smartphone app on 28 April 2025 as a PDF file. I eventually found how to download it and, once download was completed, I was presented with a choice: OneDrive, PDF reader, Bradesco, CAIXA or Drive. The only option that made the remotest sense to me was the PDF reader.

I clicked on the PDF reader icon. I was presented with an incessant torrent of glossy adverts for cars and all kinds of other products, which had absolutely no relevance to what I was trying to do. Lots of the displays seemed to have no means of exit without clicking on a 'continue' button to go ahead with buying whatever product was in the advert. An absolute buggeration. Somehow, this first time, I was able to 'display' the PDF file as shown below:

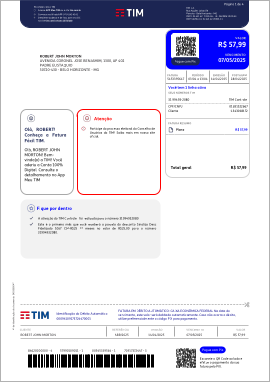

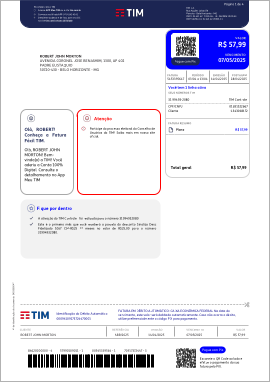

The image [shown on the left] was 72 mm wide and 101 mm high. The essential print was so tiny that it was below the graphical resolution of the screen. I was unable to enlarge it, otherwise the whole document wouldn't have fitted on the screen and it can be scrolled neither vertically nor horizontally. It was completely illegible and hence totally useless to me.

The image [shown on the left] was 72 mm wide and 101 mm high. The essential print was so tiny that it was below the graphical resolution of the screen. I was unable to enlarge it, otherwise the whole document wouldn't have fitted on the screen and it can be scrolled neither vertically nor horizontally. It was completely illegible and hence totally useless to me.

Sending the PDF file to the CAIXA or Bradesco banking apps on the phone could not possibly give me any better visibility of this miniscule image. I was left with OneDrive or Drive [which I am led to think are cloud stores pertaining to Microsoft and Google respectively]. I have an account with neither.

I've subsequently tried to redisplay the PDF and got trapped in one of the randomly cycled ads that allows no escape other than to power off the phone and reboot it!

I don't use OneDrive or Drive for reasons explained in my article Who Owns Cyberspace? Presumably the intention is for me to upload my phone bill to one of these cloud stores then download it to my computer to display or print it at a legible size.

The solution I finally adopted was to connect my phone to my computer via its USB cable and access the phone's file system using the Thunar file browser. Thus I was on much more familiar ground. I hunted through the phone's file system until I found the PDF file containing my phone bill. I then simply copied it across to the TIM folder that I had set up on my computer.

From there I could display it in the standard PDF reader on my 25-inch screen. And without any nauseating adverts. Beautiful. From there I could print the bill on A4 paper thereby getting to where we were in the good old days of paper bills, although the cost of the paper and printing ink would now be mine and not that of the phone service operator.

Notwithstanding, I chose not to print the bill because the bank's ATM's can rarely read the bar code on a bill printed on a home printer, so I'm inevitably always left with the laborious task of keying the 48-digit bar code number into an ATM at the bank. So I simply write down this pesky 4 by 12-digit numeric bar code on a piece of paper and take it to the bank. There, with my failing vision, I struggle to key it in, under bad lighting, to an ATM, whose key labelling is almost completely warn off with use. This is a two kilometre round trip on which, being 82 years old, I have fallen flat on my face four times so far due to the appalling state of the resident-maintained pavements.

With evermore of what used to be the job of corporate staff off-loaded onto the shoulders of the customer, this is the easiest solution I can come up with. But for how long will this option remain permitted by the Android framework? I remember using an SD card in my phone years ago, which, after an Android update, became permanently inaccessible. And with a closed source system, that's the end of the matter. One lives in hope.

I could embark on another laborious solution of setting up a Bluetooth link between my phone and computer. However, my air-gapped main computer, since it contains vast amounts of private data, is deliberately unequipped with Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. I think Bluetooth is too complicated anyway.

It was the young relative I mentioned earlier who rescued me from the problem with the initial payment by paying it via his own smartphone.

Of course, I paid him back. Notwithstanding, because of my age and failing vision I was unable to use the free PIX service via the CAIXA ECONÔMICA FEDERAL banking app, I had to pay via an ATM at the bank itself. For this I was charged a whopping R$15.00. That's 25·87% on top of the monthly bill of R$57.99, bringing my total bill to R$72.99. That's over 6 times the R$11.95 real value of the basic vital service that I want. So, as always, under a capitalist economy: the poor pay more — a lot more, as do the elderly, infirm, deficient and inept. But alas, such a society feels no shame. But let them each be aware: everybody gets old eventually.

My young relative has since kindly offered to school me in the use of the CAIXA ECONÔMICA FEDERAL banking app facility for paying bills by PIX [the Brazilian Central Bank's universal instant payment system]. I'll be taking up his offer. But I am bound to have a long hard time with my magnifying glass. In the meantime, it seems that there is nothing to stem the accelerating growth of digital exclusion in modern society. But there's nothing I can do about it.

One rather glaring and nasty thing about this first bill is that its charge period ran from 03 April [when I bounght the plan] to 13 April [their decreed end of the monthly charge period. Although this was only 10 days of service, TIM charged the full price of R$57.99 for the month. The following month for 31 days service, TIM charged the same: R$57,99. Another nasty piece of corporate pilfering.

Regarding the TIM service, I'll just have to see how it goes. It stinks, but what else can I do? I have no choice: it's the cheapest service they provide.

The Third Bill

I received my third bill from TIM on Tuesday 01 July 2025. I noticed immediately that the amount charged was higher than the contract. I looked at the bill. It included a fine for 'late payment' and an interest charge. I had paid the previous two bills as soon as I realised the automatic debits [which TIM had insisted that I authorise] had not happened. I decided to wait a week to make sure the debit wasn't going to be taken as arranged, but later than the prescribed date.

Of course, the payment deadline is 07 July, allowing me a window of only 6 days to make the payment. Consequently, I m not allowed to be away from home within the first 6 days of any month without being fined and charged with interest for the privilege. In other words, I'm really under house arrest for the first week of every month. There is no mechanism for paying a bill early [in anticipation]. I think this is a wholly despicable way of doing business. But in Brazil, it seems to be universal. There is only one law: Might is Right.

With the first two bills, I did not pay immediately by manual means because the app had 'confirmed' that I was on automatic debit and that the money would be taken from my account by TIM on the appropriate date. And, I didn't want to pay twice. It is for this that I was fined: not because I had deliberately withheld payment. Fines are a form of punishment. I was thus 'punished' for late payment.

The whole confusion was caused by TIM insisting that I pay by automatic debit and then not taking the money by that means. It was TIM's fault. But please note: TIM wasn't 'punished' for its automatic debit failure [about the occurrence of which it didn't even bother to advise me]. It was TIM's failure: I was the one who was punished. Again, Might is Right. So there's no point in me trying to do anything about it.

NOTE: in Brazil, apparently, it is not only courts of law that can impose fines and it is not only banks that can charge interest. It appears that any stronger party to a contract can do either or both. For instance, the dominant clique of residents in a condominium can charge whatever fines and interest it deems appropriate. The 'fine' for paying 1 day late for instance in the condominium where I live is a swingeing 10% of the value charged! Again, one cannot be away from home within the first 5 or 6 days of any month without being punished. Before the advent of the present ridiculous technology, one simply left a cheque with the condominium manager: simple, easy and you didn't get punished!

Of course, the amount of the fine and interest charged by TIM was very small. But the principle is Draconian and of very bad taste, especially in view of the fact that for only 10 days service in the first month TIM had the audacity to charge me a full month. All this is even more impudent bearing in mind that 79·4% of what I am charged is for bundled services I do not want, do not need and cannot use!

The TIM Smartphone App

It appears clear to my perception that the TIM smartphone app — as with the vast majority of smartphone apps — is not designed for the user's benefit. It is designed for the benefit of the corporate provider. Its function is primarily to create an aggressive advertising opportunity through which users may become easily beguiled or trapped into subscribing to additional services or more expensive plans — often inadvertently or without even knowing.

For me, the TIM app is a mass of confusion. It is for me complicated, incomprehensible and financially dangerous. And while it does present some usable information like data usage, it is essentially a means of blasting me with advertising.

I have been searching for legitimate information when an ad for a plan or service suddenly replaces the current screen content. This provokes the strong possibility that I could be going to touch a control on the old content, which, by the time my finger gets to the screen, has been replaced by a button on an ad that, if touched, would convey my acceptance of a new plan or an even further additional service that I don't want.

The cost of the new plan or service will then appear on my monthly bill, which if I refuse to pay will land me on the universal instrument of corporate extortion called Serasa Experian, which will make me a financial persona non grata.

For this reason I uninstalled the TIM app from my smartphone on 05 June 2025. I can only hope that I continue to receive [legible] telephone bills by email on my computer. I cannot find any option for receiving paper bills any more, which is what I would very much prefer. Consequently if I should lose my internet connection for any significant amount of time, I will be unable to pay and hence be placed on Serasa Experian's list of bad debtors.

Justice and respect for the individual: zero.

Real Consumer Protection

Most purchasers of mobile telephone services will be 'good children' and simply accept what they are offered without thinking about it. Few of them will even consider it to be unfair and think that "that's just the way it is". Even fewer will know about consumer law, let alone Article 39 that prohibits unconditional product bundling. And only a very few of them will take action via the government's consumer protection agency or the telecom watchdog.

Only up to about 5 years ago, I would make complaints via ANATEL, the telecom watchdog, or the consumer protection agency. Now, however, gaining access to the appropriate websites and the procedures involved have become so much more difficult and treatment of my cases evermore superficial that I am now no longer able to do this.

Consequently, the number of customers who take positive action against having to pay for bundled services they don't want is minuscule compared with the total number of customers. For the service provider, therefore, the cost of those few actions taken against it are insignificant compared with the gain from breaking the law and forcibly bundling-in those extra services. It's simply a cold calculation of cost/benefit risk assessment. So millions of people across the whole spectrum of incomes — the rich, the poor the old, the infirm, the deficient and the inept — will continue to be ripped off by telecom service providers.

The only way to stop this is to make consumer protection proactive: agents, without conflict of interest, proactively vetting how these services are sold by posing as potential customers and taking a class action against the service providers with consequences that actually hurt them. Or, better still, replace them all with a non-commercial organ of publicly accountable telecommunications infrastructure. And that final comment isn't political: it's purely systemic.

© May-June 2025 Robert John Morton

The Internet

The Internet

The image [shown on the left] was 72 mm wide and 101 mm high. The essential print was so tiny that it was below the graphical resolution of the screen. I was unable to enlarge it, otherwise the whole document wouldn't have fitted on the screen and it can be scrolled neither vertically nor horizontally. It was completely illegible and hence totally useless to me.

The image [shown on the left] was 72 mm wide and 101 mm high. The essential print was so tiny that it was below the graphical resolution of the screen. I was unable to enlarge it, otherwise the whole document wouldn't have fitted on the screen and it can be scrolled neither vertically nor horizontally. It was completely illegible and hence totally useless to me.