Ch07: Footnotes

Need for Community

Basic Human Needs

Body Fuel

Earning a Living

New Technology

Nuclear Family

Body Fuel

Human Worth

Scientific Method

Social Class

Elastic Yardstick

Team Co-operation

According to anthropologists, each human being is capable of knowing up to 150 other human beings personally and in detail. There are many living examples of this natural optimum for the size of human groupings. Some suggest that this limit is set by the physiology of the human brain.

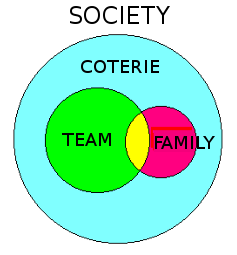

Society comprises a veritable labyrinth of structures. The most fundamental of these is the family. This is a purely natural structure held together by biological relationships. There is also a type of structure in human society called the team. This is more of an intellectual structure in that a team is formed by conscious design and is held together by the complementary abilities of its members as the combined means in meeting the objective for which it was formed. There are also civil, administrative, economic and commercial structures. These purely artificial structures are built to serve the ambitions of certain powerful individuals and cliques. A social class, on the other hand has no inherent structure. It is simply an aid to human perception which groups together people with common qualities or circumstances.

There is, however, a further natural structure within human society. It is an anthropological structure, which the artificial structures of our modern society have progressively eroded and now almost totally destroyed. It is called a coterie. A family or a team is what we may call an absolute structure. It appears the same to everybody. This is true also of the artificial social structures. A coterie, on the other hand, is different. It is a relativistic structure. It is society as perceived and experienced by the individual. It may be visualised as a circle scribed upon the social vector plane, with the individual at its centre. Its periphery is that individual's social event-horizon.

There is, however, a further natural structure within human society. It is an anthropological structure, which the artificial structures of our modern society have progressively eroded and now almost totally destroyed. It is called a coterie. A family or a team is what we may call an absolute structure. It appears the same to everybody. This is true also of the artificial social structures. A coterie, on the other hand, is different. It is a relativistic structure. It is society as perceived and experienced by the individual. It may be visualised as a circle scribed upon the social vector plane, with the individual at its centre. Its periphery is that individual's social event-horizon.

Those with whom one's relationships are strongest are close to the centre of his circle. This usually places his family close to the centre, along with teams of which he is currently a member. Being relativistic, each individual's coterie is unique. It is his point of view. It is his personal experience. His family and his team are, in this context, part of his coterie. They are part of the relativistic social continuum stretching outwards from himself to his social event horizon. As such, his family and teams are not here seen as the absolute structures they are on paper. Instead they are viewed from the inside outwards from his personal niche within each of them.

An individual's coterie comprises everybody who knows him well enough to trust him. They know what he is good at and how good he is at what. Members of his coterie have all the necessary and sufficient knowledge about him to be able confidently to make the decision as to whether or not they should rely on him to carry out a given task or fulfil a specific obligation. They are those with whom he has total credibility.

A person's coterie is the group of other human beings he knows personally as specific and unique individuals. I have heard it said that scientific observation shows that there is an optimum size for a coterie, and that it is roughly 150 people. It seems that the human mind has what may be crudely thought of as 150 cerebral pigeon holes in which it is able to hold details on the people its 'owner' knows. These details are what makes up his view of society. They are what society is from his point of view. It is supposedly a kind of mapping within the brain of the individual's social environment.

The human brain maintains many mappings for limbs and other parts of the body. It is the hands, I believe, which have among the largest cerebral resources dedicated to them. An amputee apparently retains the brain mapping for a lost limb. A severe problem arises for such a person when the mapping for an absent arm registers it as being stuck in a very awkward position — perhaps the position it ended up in during the trauma which necessitated the amputation.

The human life-form is not of itself a complete functional system. It cannot function in isolation from its terrestrial environment. Its needs of life can only be acquired from nature. It needs access to, and the use of, natural resources as a means of turning its labour into both its physical and intellectual needs of life. It also has a social need and a spiritual need. The human life-form cannot function correctly in isolation from a minimal mass of others of its kind. These are also part of the complete functional human system.

Consequently, the human brain has mappings which model an individual's physical, economic, intellectual, social and spiritual environments. Any human life-form which is denied the use of the earth's biosphere to transform its labour into its needs of life is therefore also an amputee. Perhaps even more so is anybody who is denied social contact. This is the ultimate misery of the poverty which unemployment artificially imposes upon so many in the world today. It is the deliberate amputation of the most vital of human 'limbs' by ruthless self-seeking profit-driven capitalists who are allowed to do so by an apathetic deluded majority in an uncaring society.

This optimal maximum of 150 for the size of the cerebral mapping for a person's coterie is evinced by many real-world examples. It is the natural maximum size for a village in tribal, nomadic or agrarian societies. It is the size of an infantry Company — the largest unit in which the leader — an army Captain or Major — is expected to know all his men individually. Some American religious groups make it the size to which a congregation may grow before it is split into two. It is also becoming adopted as the ideal size for an industrial unit.

Each human ability does not appear equally in everybody. One person is good at some things: another person excels at others. As producers, we are each to some degree specialists. On the other hand, our needs are diverse and can be met efficiently only by the co-operative use of the full range of human skills. Each of us is thus a specialised producer and generalised consumer. Consequently, the only way we can acquire all our needs is to exchange what we have for what we don't — to trade. Trade enables each to benefit from the special skills, abilities and possessions of all.

But trade does not come easily. Simply introducing yourself to somebody who wants what you can provide will not normally result in a trade. This is because they do not know you. They therefore have no idea about how good or bad you are at what you hold yourself out to be good at. They do not know your strengths or limitations. They have no feel for your character or integrity. You have no credibility with them.

You can trade successfully only with people you know and who know you, or in some cases if you both know somebody else in common. You need a channel of trust. The depth and quality of interpersonal knowledge required to build and maintain a channel of trust can only be truly facilitated by a coterie. In the past, this was simply one's tribal or village community. Here, everybody knew everybody simply by living and working in constant physical proximity.

A tribal village, a nomadic entourage, an agrarian community, an infantry Company, a religious congregation or an industrial production unit are all examples of contiguous coteries. They are made up of people who all live or work together in the same piece of physical space. On the other hand, my coterie is made up of individuals who are thinly scattered throughout the whole country. Many are now abroad. They consist of extended family and relatives, friends I have made at various times throughout my life, colleagues I have worked with at places of past employment and people I have done business with or helped.

My coterie thus comprises people who are almost all outside my day-to-day physical space. I can no longer interact with them directly. My only possible means of contact with them is the global transport and communications infrastructure. I cannot afford to travel on busses, trains, boats and planes. The mail is not sufficiently interactive and is becoming ever more expensive and unreliable. Telephone calls of durations necessary to maintain day-to-day closeness are far beyond my means. The only channel I have left through which to keep in touch with all the members of my coterie is the Internet.

But for how long will I have access to the Internet? ISPs are increasingly going over to the credit card as the only means of paying for Internet access. Being unemployed and living on basic State welfare, I cannot have a credit card. If the almost unique ISP through whom I still have access should decide to terminate the option to pay annually by cheque, then I shall be cut off from contact with the outside world altogether.

Capitalist free market society requires the common individual to do whatever he can to find the kind of work to which he is suited. He is required to move to wherever a member of the favoured few will condescend to offer him employment. He must leave the place of his family and social origins. Contact with his formative locale and trusted peers gets long, narrow and tenuous. It finally breaks. He works by day alongside other human life-forms with whom he shares no history. He rests lonely by night in a glorified work camp called a housing estate. He is a stranger in a strange land.

Families and communities have thus become scattered over the face of the earth. Their members no longer share the same physical space. Formative peers are disconnected from each other. They can no longer act collectively. They can no longer trade each among his own what he has for what he needs. They have been divided and conquered by capitalism.

The individual's coterie has become global and virtual, often relegated to the relative darkness of cyberspace. It has been made of no effect. Interpersonal trust has been successfully destroyed. In fact, it now rarely has the chance to take root in the first place. Without it, the individual no longer has the confidence to trade directly with his peers. The capitalist elite fill the vacuum of trust they have created with false images which pour out daily from their gargantuan marketing machines.

If life is ever again to be truly fulfilling, we must each rebuild our individual Jerusalem — the coterie of individuals we know, love and trust. To do this we must re-establish the natural human community. To do this we must first destroy that which destroyed it.