Ch03: Footnotes

The Lunar Cycle

Ancient Texts

Bible Anomalies

The Gospel

Tax & Tithing

Holy Spirit

Fuzzy Overview

Language Barrier

Life After Death

Human Destiny

Religon/Disclaimer

Salvation

Tick-Box Forms

Vida Após da Morte

Tithing — giving one tenth of your increase — is not the same kind of thing as giving one tenth of your wage or salary. It is systemically different and cannot be equated to it or implemented on the same basis within the context of a modern capitalist free-market economy.

The word tithe is not used today, as far as I know, outside the context of religion. It means a tenth part of a quantity of something. In the context of the biblical text, it refers to a tenth part of a quantity of some kind of consumable necessity of life. The biblical text defines 3 different tithes as follows.

And all the tithe of the land, whether of the seed of the land, or of the fruit of the tree, is the LORD's ... And concerning the tithe of the herd, or of the flock, even of whatsoever passeth under the rod, the tenth shall be holy unto the LORD. Leviticus 27:30-32

All this stuff was given, apparently, to the Levites. And they gave a tenth of that to Aaron (Book of Numbers 18:24-28). It seems to have been a kind of taxation to support the religious organization that administrated the nation of Ancient Israel.

Thou mayest not eat within thy gates the tithe of thy corn, or of thy wine, or of thy oil, or the firstlings of thy herds or of thy flock, ... But thou must eat them before the LORD thy God in the place which the LORD thy God shall choose. Deuteronomy 12:17-18 [reiterated in a slightly different context in Deuteronomy 14:22-23]

This was a second tenth but it was not really a tax as such because you did not have to pay it to any outside authority. It was to be consumed by you and your family, including your servants and guests. However, it was to be spent exclusively for a specific purpose. It was to be used for travel, accommodation and expenses to journey to the special place where the 3 big religious festivals were held each year.

At the end of three years thou shalt bring forth all the tithe of thine increase the same year, and shalt lay it up within thy gates: And the Levite, (because he hath no part nor inheritance with thee,) and the stranger, and the fatherless, and the widow, which are within thy gates, shall come, and shall eat and be satisfied. Deuteronomy 14:28-29

This to me looks like a kind of welfare system whereby those who have the means to produce the needs of life are required to sustain those who do not. Every 3rd year, those who had the means of economic production had to put by a third tithe of their increase to provide social security. It doesn't seem a bad system to me.

Alternatively, from the biblical wording, one could construe that it is commanding the householder to donate his normal first tithe every third year to the stranger, the fatherless and the widow. Not surprisingly, however, this interpretation is generally overlooked, since it is obviously not in the best interests of a modern tithe-demanding evangelist.

There are 3 tithes, one of which is only required every 3rd year. In all, this is equivalent to 2 tenths + a third of a tenth, which is effectively 23·33% of your increase. However, the biblical instruction is not that you take a third of a tenth each year for the third tithe but that you take the whole tenth entirely out of the increase of the third year itself. This does leave me wondering what the stranger, the fatherless and the widow ate during the other 2 years. There must have existed some means of storing and distributing the third tithe which is not mentioned within the biblical text.

Extracting the list of stuff from the above passages we get: seed of the land, fruit of the tree, corn, wine, oil, firstlings of herds (oxen) and of flocks (sheep). The Second Book of Chronicles 31:5 adds honey and Nehemiah 10:37 adds dough.

I'm not sure about dough, but everything else is produced directly by autonomous natural processes. The quantities produced are determined entirely by biological metrics. They are in no way a function of the amount of human labour expended in acquiring them. Let us now examine the amount of increase that these purely biological metrics achieve.

Modern wheat produces a median yield ratio of around 70. This means that for every kilogram of seed you plant, you will be able to harvest 70 kilograms of seed. Since you had to plant 1 kilogram of seed, your increase is only, in effect 69 kilograms. You need to take off 1 kilogram of your harvest to plant next year. Of course, modern wheat has been selectively bred under laboratory conditions and has thereby been engineered to maximize yield. It is also fed by modern fertilizers and protected by modern sprays. The merit or otherwise of this is a different subject. In ancient times, the yields of serials, trees and animals was not so high, although in compensation, they were probably less susceptible to diseases.

Modern wheat produces a median yield ratio of around 70. This means that for every kilogram of seed you plant, you will be able to harvest 70 kilograms of seed. Since you had to plant 1 kilogram of seed, your increase is only, in effect 69 kilograms. You need to take off 1 kilogram of your harvest to plant next year. Of course, modern wheat has been selectively bred under laboratory conditions and has thereby been engineered to maximize yield. It is also fed by modern fertilizers and protected by modern sprays. The merit or otherwise of this is a different subject. In ancient times, the yields of serials, trees and animals was not so high, although in compensation, they were probably less susceptible to diseases.

In ancient times, without modern fertilizers, insecticides and selective breeding, the yield ratio is conservatively estimated to have been around 25. That means that for every kilogram of seed you planted, you reaped 25 kilograms of seed at harvest time. Thus you gained an increase of 24 kilograms for the kilogram of seed you had planted. Note well that this increase of 24 depends entirely on the fecundity of the wheat. It is in no way related to the amount of work you do.

In ancient times, without modern fertilizers, insecticides and selective breeding, the yield ratio is conservatively estimated to have been around 25. That means that for every kilogram of seed you planted, you reaped 25 kilograms of seed at harvest time. Thus you gained an increase of 24 kilograms for the kilogram of seed you had planted. Note well that this increase of 24 depends entirely on the fecundity of the wheat. It is in no way related to the amount of work you do.

If the fecundity of the plant were set by nature to give an increase of only 2 then you would only be able to harvest 2 kilograms for every kilogram you planted. And you would still have had to do exactly the same amount of work to plant and tend it. Of course, whether an increase of 24 provides you with enough to live on depends on whether you have enough land area for an increase of 24 to produce enough wheat to feed your family. I don't know about Ancient Israel, but Ancient Britain had a standard measure of land to support a family. It was called a hide. The precise area of a hide varied according to the quality of the land.

If the fecundity of the plant were set by nature to give an increase of only 2 then you would only be able to harvest 2 kilograms for every kilogram you planted. And you would still have had to do exactly the same amount of work to plant and tend it. Of course, whether an increase of 24 provides you with enough to live on depends on whether you have enough land area for an increase of 24 to produce enough wheat to feed your family. I don't know about Ancient Israel, but Ancient Britain had a standard measure of land to support a family. It was called a hide. The precise area of a hide varied according to the quality of the land.

In Ancient Britain, the amount of land generally reckoned to be needed to support a family was 5 acres. An acre is the amount of land that a man with a pair of oxen and a plough can till in a day. Today, in Brazil, this concept of the minimum parcel of land required for a rural self-sustaining householder is enshrined in law. The unit is called a Módulo Rural. It too varies in size like the hide of the ancient Britons. It is defined for each Município. In most places it is 2 hectares (just under 5 acres) but in others it can be 3 or 4 hectares or even more.

One has to assume that, in Ancient Israel, each household would have sufficient land to enable the natural fecundity of their crops and animals to produce a good quality of life despite the three tithes they had to deduct from what the householder family could consume themselves. Perhaps land was not a finite resource for them like it is for us today. If a householder did not have enough, perhaps he could just annex a little more wilderness. This being the case, area would not be an issue like it is for us.

The fecundity of animals is somewhat less. Sheep seem to have been a favourite of the ancients. A ewe (female adult sheep) has a gestation period of about 5 months and can sometimes produce twins. Taking into account negative factors, a sheep can produce between 1 and 4 lambs per year. A formal average I have seen is 1·33 lambs per ewe per year. Notwithstanding, unlike grain, you don't need to replant a ewe every year. She can remain productive on average for just over 4 years. So you only have to "replant" every 4 years. Being conservative, the increase would be (1·33 × 4 - 1) ÷ 4 = 1·08. That is an increase of 108%. However, this does not include the gain you get from the wool, so the real increase is more.

The fecundity of animals is somewhat less. Sheep seem to have been a favourite of the ancients. A ewe (female adult sheep) has a gestation period of about 5 months and can sometimes produce twins. Taking into account negative factors, a sheep can produce between 1 and 4 lambs per year. A formal average I have seen is 1·33 lambs per ewe per year. Notwithstanding, unlike grain, you don't need to replant a ewe every year. She can remain productive on average for just over 4 years. So you only have to "replant" every 4 years. Being conservative, the increase would be (1·33 × 4 - 1) ÷ 4 = 1·08. That is an increase of 108%. However, this does not include the gain you get from the wool, so the real increase is more.

Cows yield even less because they can only have one calf per year. However if you let the cow live for 25 years it can produce 20 calves. Thus your increase will be (20 - 1) ÷ 25 = 0·76, i.e. 76% per year. Remember, however, that this excludes the gain you could get from the leather made from the skins of the 19 cattle you gain over the 25 years from the one original cow.

In modern farming there are costs of insecticides and fertilizers for grains and feed, medication and veterinary services for animals. Note, however that these costs arise because modern farming is enmeshed within the vicious circle of the modern economic system in which large chemical and pharmaceutical corporations actively exploit farming. But that is another rather potent subject. All in all, it seems that vegetarians get a vastly superior increase.

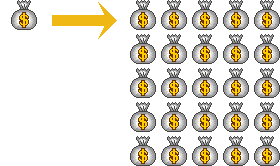

Within a modern Free-Market economy, the precarious equivalent of the natural fecundity of plants and animals is return on investment. The natural economy of Ancient Israel is thus equivalent to a modern financial return on investment of 25-fold year on year for grain. That is a gain of 2500% per annum. For every dollar you invest, you get $25 back at the end of the year. You therefore have an increase of $24 each year if you put your dollar back to gain you another $24 next year. Even for animals you get at least a 100% return on investment.

Within a modern Free-Market economy, the precarious equivalent of the natural fecundity of plants and animals is return on investment. The natural economy of Ancient Israel is thus equivalent to a modern financial return on investment of 25-fold year on year for grain. That is a gain of 2500% per annum. For every dollar you invest, you get $25 back at the end of the year. You therefore have an increase of $24 each year if you put your dollar back to gain you another $24 next year. Even for animals you get at least a 100% return on investment.

Out of the $24 you gain, you would effectively have to pay $5·60 in tithes. However, strictly, you should pay $4·80 for each of the first 2 years and $7·20 in the third year. You then repeat the 3-year cycle indefinitely, leaving your whole land fallow every 7th year. The tithes thus effectively reduce your increase from 24-fold to just over 18-fold (that is 1,800%). But this is still astronomically higher than the increases possible within the capitalist free-market economies of today.

Return on shares or multi-market investments in today's capitalist world is between 10% and 25% depending on the level of risk. A bit of money I put by gains me about 18% per year at the moment, although the high-risk shares have lost over 10% in the last 6 months. Interest gained in a normal savings account is generally anything from a fraction of a percent to 5%, depending on the condition of the national economy at the time. So the capitalist free market seems to be catastrophically less efficient than nature.

![]() A "petty-capitalist" citizen of a modern State gains only about (at the time of writing 16 June 2010) 2·8% per annum in his saving account at the bank.

A "petty-capitalist" citizen of a modern State gains only about (at the time of writing 16 June 2010) 2·8% per annum in his saving account at the bank.

The ancient householder, with his hide of land, gained a 24-fold increase on his seed. That is about 857 times what a savings account today will yield, and 96 times the increase gained from investing in ultra high-risk shares (assuming you don't end up losing the lot). Of course, the ancient householder was at the mercy of the fickleness of the weather. Nevertheless, he would need an awful lot of bad weather or drought over many years to reduce his increase by 96 times. Even the animals gain 36 times the yield of a savings account and over 4 times the return on an ultra high risk investment.

So what's happening here? Let's use a conservative median of comparison between "increase of the land and livestock" on the one hand and "return on investment at average risk" on the other hand. The first yields roughly 50 times what the second yields. But all economic wealth — agricultural, mineral or whatever — is ultimately produced by the Earth's biosphere: the land. This is true for the 'farmer' of Ancient Israel. It is equally true for the modern global capitalist free-market economy. So, in the case of the latter, where is the other 49 fiftieths of the increase going? To whom is it going? Or, rather, who is taking to themselves 49 fiftieths of the global increase? Should they be doing this? Were these "powers that be" put there by God for our edification? Is it their divine right to thereby relegate the majority of humanity to a state of inadequate subsistence?

The ancient householder plants his hide of land with seed. That is his work. It takes a relatively short portion of the annual cycle. Then he just needs to protect it, which is relatively light work that does not demand all his available time. But nobody is then going to put him on "short time" with a corresponding reduction in pay so that he can no longer make ends meet. He does not have to apply for social security top-ups. He does not need to sign on at the Jobcentre, having to give account each fortnight as to why he has not yet found any full-time work. He does not suffer the social stigma of being labelled a lazy unemployed layabout.

The ancient householder plants his hide of land with seed. That is his work. It takes a relatively short portion of the annual cycle. Then he just needs to protect it, which is relatively light work that does not demand all his available time. But nobody is then going to put him on "short time" with a corresponding reduction in pay so that he can no longer make ends meet. He does not have to apply for social security top-ups. He does not need to sign on at the Jobcentre, having to give account each fortnight as to why he has not yet found any full-time work. He does not suffer the social stigma of being labelled a lazy unemployed layabout.

He may then use the majority of his time to do other things. He may repair or better his home. He may travel. He may socialise with his neighbours. He may philosophise with his friends about life, the universe and everything. All the while, his income is being generated by natural processes automatically taking place in his field. His new "full-time job" is waiting for him at harvest time. But this too is relatively short-lived.

The important point is that the householder's income doesn't stop just because there is no work to be done at the time. Under a natural agrarian system, although labour be a necessary adjunct at critical times, it is not what generates the return. The tithes that the Ancient Israelites paid were from what was generated by the biological mechanisms within the plants and animals. They were not paid out of anything remotely generated by the labour of man.

The above cannot be equated to or compared with one who manages or works for a modern farm or agribusiness corporation. These operate within a capitalist free market in which the situation is totally different.

... thou must eat them [second tithe + offerings] before the LORD thy God in the place which the LORD thy God shall choose, thou, and thy son, and thy daughter, and thy manservant, and thy maidservant...

Deuteronomy 12:18

The context of the above quotation overwhelmingly implies to me that a householder was to use his second tithes to sustain his manservant and maidservant in the same way as he was to use it to sustain his son and his daughter. I therefore think it is safe to deduce that his manservant and maidservant themselves were neither required, nor were expected to save up second tithes of the food, clothing and shelter with which their master provided them. Tithes were tenth parts of what the land produced in terms of corn, fruit and animals (honey and dough as well perhaps).

You give food and shelter to your plough horse to sustain him, not to reward him. If you have a bounteous crop one year, you do not give more food to your plough horse. He will just get fat. You give food, clothing and shelter to your servant for the same reason. It is simply to sustain his life so that he can work for you. The amount you give him is nothing to do with how fruitful the field is in which he works. You may treat your servant to various good things in fruitful times. But this is something separate. It is an act of friendship or benevolence. It is not part of the master-servant socio-economic relationship.

Whether you sustain your servant by giving him food, clothing and shelter directly or whether you give him the "equivalent" in money so that he can buy these things elsewhere is simply a logistical technicality. It is exactly the same thing in principle. Consequently, there can be no systemic difference between an unbonded slave and an employee.

With minor differences in implementation, the lot of a modern employee is the same as that of the ancient unbonded slave or servant paid in kind. The fact that he is paid in money rather than goods is a minor matter of implementation. His freedom to change employers is the same as the unbonded slave's freedom to seek appointment with a different master. Social security and employee rights attempt to compensate employees (unbonded slaves) for their lack of guaranteed lifetime employment, which ancient bonded slaves automatically had by reason of their bonding.

The wage or salary of a modern employee is essentially for the purpose of sustaining him (and his dependants). It is not a reward for his work. The aim of his employer is to maximize profits by minimizing costs. His employee's wage is a cost. His quest is therefore to keep his employee's wage as low as possible.

Notwithstanding, there are counter-pressures that prevent him from reducing it too much. The needs of the human body are absolutes. They are not proportions or percentages like profit. A poor man needs the same amount to eat as a rich man if both are to be adequately fed. He needs exactly the same absolute amounts of carbohydrate, fat and protein each day.

Notwithstanding, there are counter-pressures that prevent him from reducing it too much. The needs of the human body are absolutes. They are not proportions or percentages like profit. A poor man needs the same amount to eat as a rich man if both are to be adequately fed. He needs exactly the same absolute amounts of carbohydrate, fat and protein each day.

A minimum wage is therefore a function of the physiology and biology of the human life-form, not of the market forces of supply, demand, competition and profit. It is therefore maintained to give the minimum sustenance that the labourer will tolerate that is just a smidgen above the level below which social insurrection would ensue. It is a very delicate balance.

Furthermore, the minimum wage cannot be correctly set in terms of money. This is because the value of money is different in different places. To buy the same food value in terms of the necessary amounts of carbohydrate, fat and protein consumes more money in some localities than it does in others. In reality, it is not the price of food that changes, it is how the essentially rubber dollar is stretched or squashed from one place to another.

An employer, in order to be able to compete with his peers, must always endeavour to pay his employee no more than the minimum wage upon which that employee can sustain himself within the economic environment in which he lives. So why is there such a disparity in the wages of different employees?

The reason is that for all but the most basic kinds of work, the employer needs to pay his employee an incentive to gain advanced skills in the first place. If I can make no more money as a software systems designer than I can as an unskilled labourer, then why should I expend the years of hard study and sacrifice to acquire the skills of a software systems designer? My reason is the additional salary I am promised above and beyond the minimum wage. At least, that is the theory. My salary comprises a minimum wage + a skills-acquisition incentive.

However, the employee with a professional skill is expected to make himself presentable to a degree that has come to be regarded as appropriate to his profession. Unlike the unskilled worker, he is expected to go to work in a reasonably new suit. He is expected to be able to travel to diverse places alone at the drop of a hat — something that can only be done if he owns a reliable car. So even with his salary's incentive component, he is still at the limit of being able to make ends meet in the life-style that he is expected and required to have in his profession.

But the pressure is still on the employer to keep an employee's salary to the minimum he can possibly get away with. This means that when the education system produces a glut of graduates with a particular advanced skill, the law of supply and demand enables the employer to drastically reduce the incentive component of the salary for that skill. The graduates end up being paid no more — and sometimes even less — than employees with much lower skill levels. Yet they still have to maintain themselves professionally presentable. That puts them in an even worse position than the unskilled worker.

The engine of the ancient householder's economy was the crops he planted within his hide of land. The elemental unit of this engine was the plant, a modern example of which is wheat. The wheat plant is a self-contained automatic factory. It takes in raw materials from the air and the ground. It applies solar energy that it harnesses through its leaves. Motivated by the energy it absorbs, it assembles its finished biological product, by a single composite process specified by a program stored within its DNA and executed by mechanisms within its cells.

The modern corporation's counterpart of the ancient householder's hide is still the land. A large agribusiness still gains from the land in the same way. Oil companies get their increase from beneath the land from what the land itself produced millions of years ago. Mining Corporations get their increase again from beneath the land. All other layers of the economy gain their increases by applying human labour to add value to what the base-layer enterprises get from the land.

The main difference is that nature's factory goes from raw inputs to finished product in a single composite step. A modern economy divides the process into a hierarchy of separate layers. In the case of the modern economy, the mechanism within the cell that executes the program for constructing the product is the human labourer. Differently again, it is also human labour that designs the product and the program for constructing it. This is where the higher-level skills are required.

The upshot is that the human labourer — the employee — is part of the corporate employer's wheat plant. The ancient householder's wheat plants did not themselves pay tithes. Neither should the modern wage-labourer. He is not the master who gains the increase. He is just part of the mechanism that creates it in return for the minimum sustenance which he needs in order to survive and work.

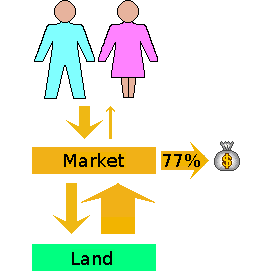

The labourer receives a wage, which is tuned to a level that is just sufficient for him to live on and have an incentive to acquire the various skills employers seek. His labour, on the other hand is a vital element in the creation of his employer's increase (profit). But the labourer does not receive his rightful proportion of this increase, his employer does. A labourer's wage does come out of his employer's increase. However, the rest of that increase is siphoned off as corporate profit and State Revenue. In the case of the UK during the early 1990s, 77% of the wealth created by an employee's labour was siphoned off in this way.

The labourer receives a wage, which is tuned to a level that is just sufficient for him to live on and have an incentive to acquire the various skills employers seek. His labour, on the other hand is a vital element in the creation of his employer's increase (profit). But the labourer does not receive his rightful proportion of this increase, his employer does. A labourer's wage does come out of his employer's increase. However, the rest of that increase is siphoned off as corporate profit and State Revenue. In the case of the UK during the early 1990s, 77% of the wealth created by an employee's labour was siphoned off in this way.

The labourer is the motive force within this employer's "wheat plants". In Ancient Israel, neither sons, daughters, menservants, maidservants or wheat plants paid tithes. Neither should the modern wage-labourer.

In any case, the whole concept of tithing is systemically unsound. The basic needs of life comprise specific quantities of carbohydrate, fat and protein. Consequently, for tithing to work justly, it is necessary to work backwards from your basic needs of life to the amount you need to plant in order to supply those needs plus the tithes.

You can't simply start with a given increase (in the ancient context) or a given wage or salary (in the modern context), deduct the tithes, and necessarily end up with enough to live on. It just doesn't work. You will most likely find that taking 23·33% from your gross wage or salary will leave you and your family inadequately nourished and living in gross hardship.

Certainly, if you are living at or near the minimum wage, you can rest assured that it has been calculated, taking into account income tax and all possible deductions, to leave you with the absolute minimum upon which one can possibly survive. This is far more the case for those living on social security.

Consequently, in the context of a modern wage or salary, tithing is systemically unworkable. Even in the context of the ancient householder, it cannot be implemented as stated in the biblical text without making some significant assumptions that are nowhere mentioned therein. The only way a tithing system could be justly implemented is to proceed as follows.

Calculate the carbohydrate, fat and protein requirements of each member of your family (household) in megajoules per year.

Work out a crop mix to provide a balanced diet containing also the necessary trace-elements. Calculate the amount (kilograms) of each crop required to provide your family's needs.

Work out the area and seed quantity you need to plant to yield just over 1·3 times this amount. The "·3" provides the extra you need to cover tithe obligations. It is also expedient to multiply this result by a further factor to provide a contingency against a bad year with a lower yield than expected.

Commandeer the amount of land necessary and plant it accordingly. Harvest your crops, pay your tithes and store the rest to consume as you need.

Notice that the flexibility in the above procedure is in the terrestrial resources (land) that are available to you. It must be assumed that you are able to commandeer sufficient land to plant the necessary area of crops. It also assumes that you are not required to pay any revenue, taxes or rent to any overlording authority like a State, corporation or noble landlord.

If you are a modern salaried or waged labourer, you're stymied. Your ultimate resource is fixed by your employer or the State. You cannot simply commandeer more salary to cover your tithe obligations to God or to whatever religious organization you accept as representing Him here on Earth at the moment. You have to accept what you are given. And increasingly in the world today, what you are given bears little or no relationship to how skilled you are or how hard you work. You are completely boxed in.

So in the modern context, the waged or salaried labourer should never be paying tithes to anybody or any organization.

Yet we hear many a wild-eyed evangelical pastor thundering the words of Malachi to his cringing flock:

Will a man rob God? Yet ye have robbed me. But ye say, Wherein have we robbed thee? In tithes and offerings. Ye are cursed with a curse: for ye have robbed me, even this whole nation. Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse, that there may be meat in mine house, and prove me now herewith, saith the LORD of hosts, if I will not open you the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it. Malachi 3:8-10

Of course, the pastor wants to justify the income he extracts from his flock for his own rather more than adequate lifestyle and for the furtherance of his self-appointed ministry. But just remember the difference in the socio-economic context between the terrestrially-resourced land-possessing householder of ancient times and the waged or salaried employee of today's capitalist free-market economy.

I wonder how many of the pastor's flock suffer in silence, gripped in the bondage of faith, not daring to show any sign of dissidence for fear of being shunned by their peers and branded as disloyal to Jesus Christ.

They should tell their pastor to go thunder his message at the giants of agribusiness, global oil companies, transnational mining corporations and rent-charging landlords in their rambling estates. See if he dare. They, and they alone are required, as far as I can see according to the biblical text, to pay the tithes. I wonder how many do.

The raw significance of something written thousands of years ago, in completely different circumstances, cannot be arbitrarily transplanted into a blindly-assumed modern context. Whatever mycelium of truth may be buried within the biblical text, it cannot be unravelled that way.